Rogue Heroes: The History of the SAS, Britain's Secret Special Forces Unit That Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War (4 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #World War II, #History, #True Crime, #Espionage, #Europe, #Military, #Great Britain

Stirling was also possessed of a profound self-belief, the sort of confidence that comes from high birth and boundless opportunity. He was blithely unconstrained by convention, and regarded rules as nuisances to be ignored, broken, or otherwise overcome. He was elaborately respectful toward his social inferiors, and showed no deference whatever to rank. Strikingly modest, he was repelled by braggarts and loudmouths: “swanks” (swanking) or “pomposo” (pomposity) were his gravest insults. His manner seemed vague and forgetful, but his powers of concentration were phenomenal. Despite an ungainly body and a patchy academic record, he had a stubborn faith in his own abilities, intellectual and physical. Stirling did exactly what he wanted to do, whether or not others thought his aims were sensible or even possible. The SAS came into being, in part, because its founder would not take no for an answer, either from those in authority or from those under his command.

Just as he had been bored by the logistics of mountaineering, so Stirling found the practical preparations for war indescribably tedious. Like many young men, he was hungry for the fight, but instead found himself shackled to a regime of endless marching, kit inspections, weapons drill, and all the other rote elements of military life. So he rebelled. Slipping away from the Guards Depot at Pirbright, he would frequently head to London for a night of drinking, gambling, and billiards at White’s club; just as frequently he was caught, and confined to barracks. Stirling was a nightmare recruit: impertinent, indolent, and often half asleep as a result of his carousing the night before. “He was quite, quite irresponsible,” recalled Willie (later Viscount) Whitelaw, a fellow trainee officer at Pirbright. “He just couldn’t tolerate that we were being trained along the lines of the last major conflict. His reaction was just to ignore everything.”

It was at the bar of White’s, one of the most exclusive gentleman’s clubs in London, that Stirling first learned about a form of soldiering that seemed much closer to the adventure and excitement he had in mind: a crack new commando unit intended to hit important enemy targets with maximum impact. Stirling’s cousin Lord Lovat had been among the first to volunteer for the commandos.

Formed under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Robert Laycock, the force—christened Layforce—would consist of more than 1,500 volunteers formed into three commando regiments, recruited from the Foot Guards (the regular infantry of the Household Division) and other infantry regiments: an elite troop of specialized, highly trained raiders and marauders. Lord Haw-Haw, the British traitor who broadcast radio announcements into England for the Nazis, would describe the commandos as “Churchill’s cut-throats.”

Stirling immediately volunteered. Soon he found himself stomping through the wilds of western Scotland, familiar boyhood terrain and far from the parade ground he loathed. For weeks the commandos trained in the bogs and bracken of the Isle of Arran: route marches, unarmed combat, endurance, fieldcraft, navigation, and survival techniques. Even at this early stage, some of the other volunteers noticed something different about the tall young officer: Stirling was a natural leader, with an understated but adamant faith in his own decisions and a gentlemanly insistence on doing everything he asked of his men, and more. On February 1, 1941, Layforce sailed for the Middle East. Finally Stirling was heading into battle, leaving behind a long string of unpaid bills—from his bookmaker, his tailor, his bank manager, and even from a cowboy outfitter in Arizona, seeking payment for a saddle.

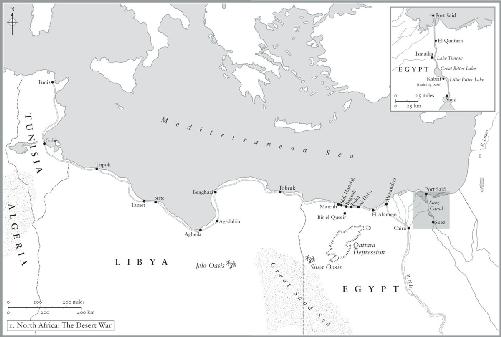

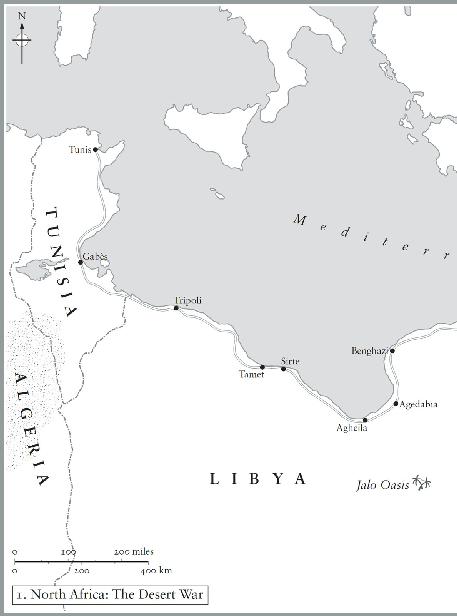

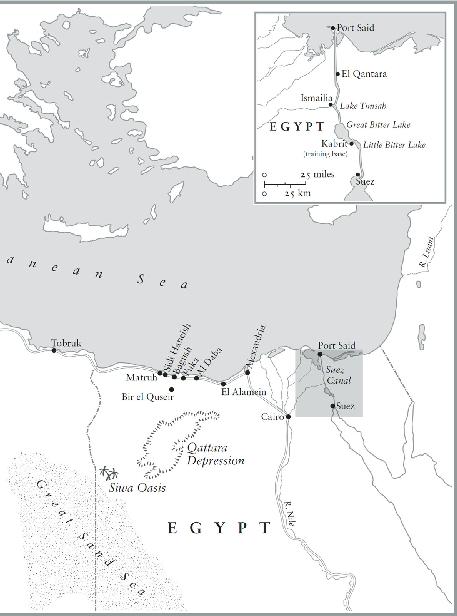

Layforce had been deployed to disrupt Axis communication lines in the Mediterranean, and to spearhead the capture of Rhodes. But by the time the commandos arrived in Egypt, the military situation had changed: the arrival in Cyrenaica (eastern coastal Libya) of the Afrika Korps, the German expeditionary force under Erwin Rommel, had transformed the strategic picture. The British were now scrambling to oppose the German advances, and the first stage of the seesaw war in North Africa was under way. Initially deployed to shore up the Italian defense of their North African colonies, the Afrika Korps moved with alarming speed, driving the British back to the Egyptian border with Libya and laying siege to the coastal town of Tobruk. Instead of storming Rhodes, the commandos were split up and variously deployed to garrison Cyprus, cover the evacuation of Crete, reinforce the defense of Tobruk, and carry out raids along the coasts of Cyrenaica and Syria. An assault on the Libyan coastal town of Bardia achieved little, with 67 of the British raiders taken prisoner. Of the 800 commandos sent to cover the evacuation of Crete in May, fewer than 200 managed to escape—among them Evelyn Waugh, who boarded the last ship to leave. In June, the commandos successfully established a bridgehead on the Litani River in Lebanon against Vichy French forces, but lost a quarter of their attacking force.

Stirling, based in Egypt with the Layforce Reserve, was bored and frustrated. He had yet to fire a gun in action. “We were involved in a series of postponements and cancellations, and that was extremely frustrating,” he later recalled. Before the departure of the commandos, the director of combined operations had told them they were about to “embark on an enterprise that would stir the world.” So far, Stirling had barely stirred. As always when he was underemployed, he turned to revelry. Peter Stirling, David’s younger brother, was serving at the British embassy in Cairo, and his comfortable diplomatic flat in the Garden City district became the venue for riotous parties and nocturnal forays into the city’s fleshpots.

Stirling began to miss parades, and make excuses. His claims of ill health were not wholly untrue. He was stricken by a nasty bout of dysentery. Then, returning from a night exercise, he tripped over a tent rope and gashed an eye socket, requiring stitches. Stirling found the American hospital particularly comfortable, and began to contrive to spend his days there, claiming to be suffering from fever. “In a sense, I was pretty ill,” he later argued. “Because I would go out in the evening, having recovered from the appalling hangover caused by the previous night’s activities in Cairo, and re-establish my illness by my activities the following night.” Alerted by the hospital matron, Stirling’s superiors began to question just how unwell he really was. He was drinking and partying himself into serious trouble when his life was changed by a conversation, in the mess, with Lieutenant Jock Lewes, a fellow officer in the commandos who was as self-disciplined and uptight as Stirling was dissolute and nonchalant.

Lewes told Stirling that he had recently obtained a stock of several dozen parachutes, destined for a paratroop unit operating in India but accidentally shipped to Port Said, where he had appropriated them. Colonel Laycock had given Lewes permission to attempt an experimental parachute jump in the desert. Stirling asked if he could come along, “partly for fun, partly because it would be useful to know how to do it,” and mostly because he was very bored. So began an important and unlikely partnership between two men who could hardly have been more different.

Detail left

Detail right

Lieutenant John Steele Lewes was a paragon of military virtue, a man of rigid personal austerity, and a martinet. Born in India to a British father and Australian mother, he had captained the Oxford University Boat Club, graduated from Christ Church, and seemed destined for a career in politics or the upper reaches of the army. Having joined the Welsh Guards on the outbreak of war, he was appointed regimental training officer and billeted at Sandown Racecourse. There he was painted by the artist Rex Whistler, a fellow officer and friend, sitting on the steps of the grandstand with a Bren gun across his knees, looking as if he was about to mow down the runners and riders in the 3:15.

“Jock” Lewes was almost too good to be true. “Be something great,” his father had told him, and Lewes intended to fulfill that injunction. He was athletic, rich, patriotic, and handsome, with glinting blue eyes and an immaculately tended Douglas Fairbanks Jr. mustache. He appeared in the society magazines, and was courting a wellborn and sensible woman named Miriam Barford, whom he lectured on the importance of sacrifice and hard work. “We acquire more merit on this earth in doing gladly those tasks set us which are least attractive than by any amount of enjoyable labour,” he wrote.

Jock Lewes was stern, workaholic, and slightly priggish, with a deep “contempt for decadence,” according to his biographer. He had no sense of humor, and “his austerity could be simply too much for other mortals.” “You wouldn’t find Jock catching a quick drink in Cairo or taking a flutter at the racecourse,” observed Stirling, who was usually to be found doing one or the other.

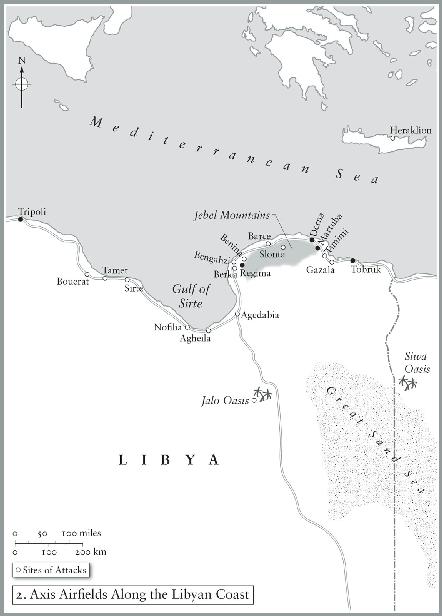

The two officers did, however, share an urgent desire for action, and a belief that the commandos were not being properly used. A rising star in Layforce, Lewes had already demonstrated his pluck and ingenuity in several operations, including a successful attack using motorized gunboats on an enemy air base near Gazala on the Libyan coast. Lewes had been impressed by the Germans’ use of paratroops in the conquest of Crete, and thought that a parachute force might prove a useful addition to future Allied commando operations. He began lobbying senior officers to be allowed to form his own, hand-picked unit, and wrote home that he had been given “that which I have longed for—a team of men, and complete freedom to train and use them as I think best.” Stirling was struck by Lewes’s calm demeanor, great professionalism, and experience. According to one version of the story, he had got wind of what Lewes was up to and deliberately sought him out in the officers’ mess. Others say the conversation was purely accidental. Either way, the ideas of Lewes and Stirling were converging.