Rogue Heroes: The History of the SAS, Britain's Secret Special Forces Unit That Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War (40 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #World War II, #History, #True Crime, #Espionage, #Europe, #Military, #Great Britain

Camp commandant Josef Kramer and Irma Grese, the warden for women prisoners, known as the “Beast of Belsen” and the “Beauty of Belsen.”

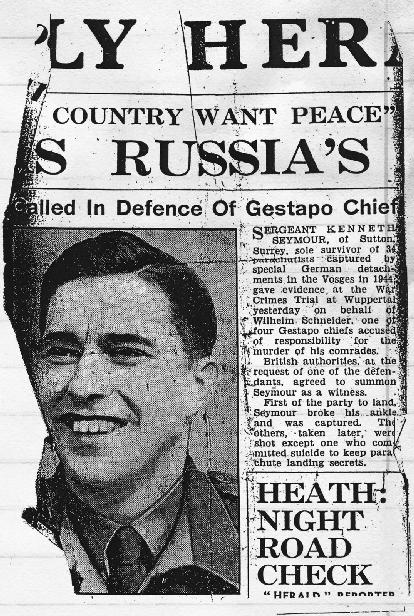

Kenneth Seymour, the young signaler injured and captured in the Vosges Mountains, whose claims to heroism were hotly disputed by his comrades.

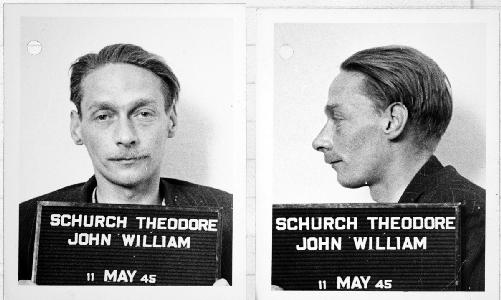

Theodore Schurch, former London accountant and secret fascist spy: the only British soldier executed for treachery in the Second World War.

Paddy Mayne’s sand-colored beret.

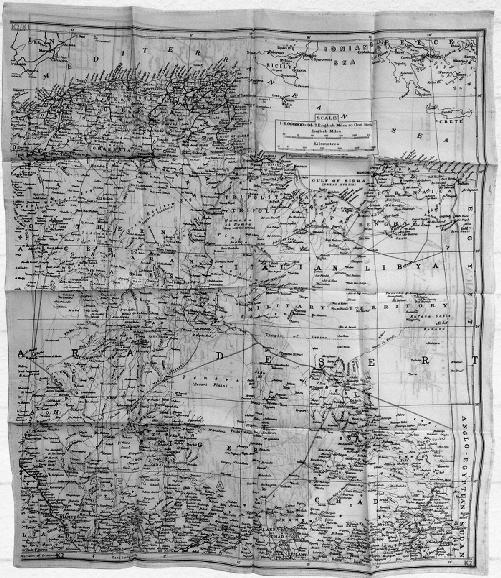

Map on parachute silk.

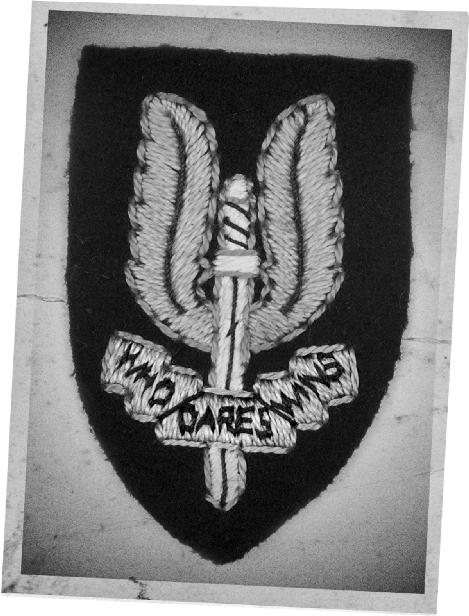

SAS cap badge, featuring the flaming sword of Excalibur and motto, “Who Dares Wins.”

SAS “operational wings,” worn by trained parachutists.

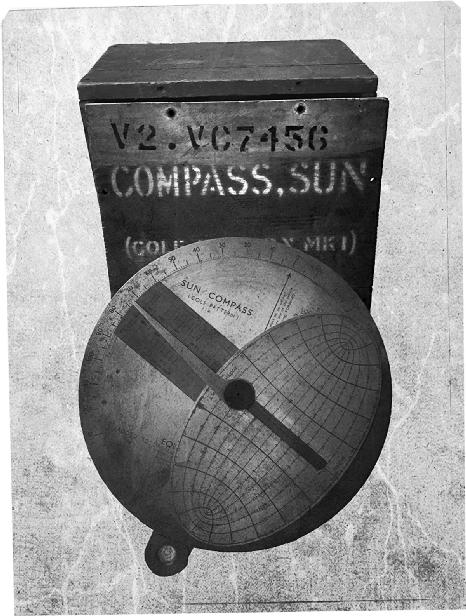

Bagnold’s sun compass, essential for desert navigation.

The Massif de Morvan, west of Dijon, is wild country: six thousand square miles of densely forested hills, remote, rugged, and sparsely populated. On the wine-making plains of Burgundy below run the major roads and railways linking Paris and Lyons, but the high Morvan is traversed only by a few forestry tracks and small roads. The villages are few and far apart, the people resilient and independent-minded. It is good country for hunting, and hiding, and fighting unconventional war.

In the early hours of June 6, 1944, nineteen men parachuted into the Morvan, the advance reconnaissance party for Operation Houndsworth, the companion mission to Bulbasket. They were led by Major Bill Fraser, as much of an enigma as he had been in the desert: aloof, probably homosexual, indestructible, unknowable. While Fraser led one stick of parachutists, the other was commanded by another familiar figure, newly minted lieutenant Johnny Cooper. Here, too, was Reg Seekings, promoted to staff sergeant major, as blunt and belligerent as ever. Their promotions, and the change in their relative ranks, seem to have had no impact whatever on their friendship. Cooper treated Seekings like a fellow officer; Seekings treated his commander as if he was still an NCO.

The Morvan, with its thick woods and steep gullies, is a difficult place to parachute into at any time; high wind, dense cloud, and rain on June 6 made it even harder. “It was a black, miserable night,” Cooper recalled. Seekings grumbled, in no particular order, about the weather, the pilot, and the kit bag he now had to jump with, attached to an ankle by a twelve-foot rope, which tended to get tangled. The pilot was unable to locate the drop zone through the clouds, so the parachutists were dropped blind, with orders to assemble at the rendezvous point as best they could. The jump was rough. The parachutists were “tossed around like feathers in a whirlpool,” Seekings recalled. Cooper hit the wall of a farmhouse and was temporarily knocked out. When he came to, he buried his parachute and set off into the night with a luminescent ball under one arm as his recognition signal, hooting in what he hoped was approximately the sound of an owl, and occasionally calling “Reg!”—all of which would surely have attracted the attention of the Germans, had any been around. Fraser landed at least a dozen miles from the rendezvous point, spotted some German troops with guns, and opted to hide out in the woods. Several men landed in trees. In the kit bag attached to his leg, Seekings had packed a large amount of extra soap, which he had been told was in short supply and could be used for trading with the French. The bag burst open on impact with the ground, sending bars of soap flying everywhere in the rain. “You could smell Lifebuoy for miles,” said Seekings. As instructed, Cooper attached a message to the leg of one of the two carrier pigeons he had brought along, and released it. The wretched bird simply sat on the ground, until it was chased across a field “to get it airborne.” The recalcitrance of the first pigeon sealed the fate of its companion, which was swiftly killed, cooked, and eaten.

It took four days for the full reconnaissance team, with the help of sympathetic French farmers and the local resistance network, to reassemble in the forest at a spot known as Vieux Dun. Fraser had chosen to set up camp alongside the headquarters of the Maquis Camille (also known as Maquis Jean), one of several partisan groups operating in the woods.

French resistance to Nazi occupation had taken on a particularly aggressive and complex form in the Morvan. The German Forced Labor Draft of 1943, requiring every young Frenchman to register for compulsory war work, had prompted hundreds to take up arms and retreat into the woods. By 1944, there were an estimated ten thousand active resistance fighters in the region. As elsewhere in France the maquis were patriotic, frequently eager, and brave, but often amateurish and underequipped, their ranks riven by betrayal and political rivalry. Seekings was scathing of the way political ambition impeded their military effectiveness. The maquis, he sneered, were “really political parties who had run away into the woods,” with leaders who shied away from fighting on their home turf “because they wanted to become local governor or mayor in that area.” Accusations of betrayal and double-dealing were bandied about with lethal effect: “Anybody they didn’t like was labelled a collaborator.”

The growing strength of the maquis in the Morvan had created a strange situation: the Germans knew that large bands of “terrorists” were operating in the forests, but hesitated to attack, since they knew that local resistance networks would give advance warning of any major troop movements, allowing the maquis to prepare counterattacks, or melt away. When the Germans did attempt to take on the insurgents, much of the muscle was provided by the Milice, the fascist paramilitary French militia formed to root out resistance. The maquis considered the French Milice more dangerous and ruthless than the Gestapo; the SAS War Diary describes them as “the most hated men in France. Traitors, cowards and bullies.” By 1944, the conflict in rural France had taken on many of the aspects of a civil war, with all the treachery and cruelty that this entails.