Romantic Screenplays 101 (16 page)

Read Romantic Screenplays 101 Online

Authors: Sally J. Walker

Tags: #Reference, #Writing; Research & Publishing Guides, #Writing, #Romance, #Writing Skills, #Nonfiction

A cinematic story can never be a boring status quo. It must move the characters through a life-changing experience. The major players must change to become something more than they were at the beginning. For the most part, the protagonists grow in a positive direction, while the majority of the antagonists suffer defeat or experience personality deterioration. “Good over Evil” you might say. However, you might tell the story of “Evil over Good” to depict a cautionary tale. Shakespeare did in “Hamlet.”

You need to identify how you want to demonstrate the

internal

change. That internal Character Arc or shift in awareness must impact the character’s

external

action choices, thus impact the events in a visual, active demonstration of the change. The visual action must be integral to the main plot of the story. How did Dustin Hoffman’s character in TOOTSIE internally change and demonstrate his change? And wasn’t that demonstration also the Climax of the story? In this instance, the movie was character-driven.

The character arc is demonstrated when the character makes a conscious choice and proceeds to act in a different manner. The change doesn’t work if it is sudden, unpredictable, or coincidental. The audience has to be cognizant of the gradual transition, hungry to go along for the ride, frustrated

with

the character, and anxious to get on with the quest. The challenges of the stressors in the plot and the character’s subsequent actions or reactions must set-up the internal growth pattern. Blatant hints don’t work either. That’s over-the-top, on-the-nose melodrama. Paying attention to the character’s psychological profile (and need to protect vulnerable self-concept) will prevent that over-exaggeration characterization-to-plot mistake. Adage: People don’t change overnight.

Does a character arc work in an action-adventure, plot-driven script? It does if the arc is integral to the plot. Sometimes the reluctant warrior merely proves his mettle as in Ryan coldly shooting the cook in THE HUNT FOR RED OCTOBER. Before that, the audience saw an intellectual man who willingly took on physical challenges as needed to prove what he felt to be true, that Ramius wanted to defect. We learned Ryan’s personal history of surviving a helicopter crash yet graduating from the U. S. Naval Academy. He was identified as a trained and courageous warrior. When he came face-to-face with the enemy, he did the deed and slept on the plane ride home. The audience saw that subtle evidence of his honorable and courageous internal motivation grown to the point of calmly accepting the personal consequences of a life-and-death decision. Bart Mancuso, commander of the

Dallas

, changed from distrust to acceptance of Sean Connery’s Ramius and willingly played submarine “chicken.” Oversimplification perhaps, but both demonstrate character arcs all the same. Their internal changes were manifested in external action.

The protagonist does not necessarily have to be the one to arc either, but, if not, he or she must

cause

the arc. Consider FORREST GUMP where Forrest was the same from childhood through adulthood. However, he changed Lieutenant Dan.

PLOTTING CHARACTER

Students and practitioners of screenwriting quickly become very familiar with the skeletal points required in every script to prevent expensive, boring, wandering story lines. These are plot points that maintain and build the suspense, whether the story is plot-driven or character-driven.

Complete character profiles ease the process of creating these plot points. The writing goes faster when a writer understands and can predict the actions and reactions of the script’s characters to get them from one signpost to the next. The profile identifies prime dramatic material in those personalities. The writer knows what the characters want, what will logically block their achievement, and how they should change. The paradigm provides a view of the plot framework of the powerful story, allowing the writer to orchestrate the progressive experiences of those characters.

The main plot is the linear story. By stating that primary story in the log line, a writer can easily ignore or eliminate extraneous images and events when the actual writing is underway. Those extras and side-trips may create milieu or aura but act as exposition rather than action moving the story forward. The log line defines the framework of the story and hones in on the essential characters needed.

What characters do you need to introduce in Act I when you set up that initial circumstance? What singular event at Plot Point I will change the direction of those characters’ lives and force them in a new direction? What needs to happen at Mid-Point Epiphany to the protagonist / lead to raise the stakes and seriously focus that person on a new goal? What would push this character into a corner at Plot Point II to the extreme intensity of “fight” rather than “flight?” How can this character’s dramatic potential build in preparation for the explosive action at the Climax?

Do not overlook the story’s time line, and how time, seasons, and routine life impact the characters’ actions and choices. Notations on the paradigm prevent overlooking the subtlety of these influences as you write the succinct narrative. Sometimes, you can discover more potential stressors in the time line and can toy with even more What-if lists. Think about the time line and lafe stages depicted in STEEL MAGNOLIAS as an example.

Next, consider each major player’s personal agenda, routine, and those notes on the character’s life-stage at in the beginning and where you want him / her by the end. What mundane material can be skipped? What hints or foreshadowing glimpses are absolutely essential for audience empathy or understanding of an important point? What would be overload? Paying close attention to these points allows you to identify necessary material and sometimes even pacing, as well as revise out extraneous-though-interesting stuff. That is the essence of what film editors do, usually with the director’s input on the vision for the story.

The protagonist’s personal agendas frequently develop into subplots essential to the main plot line. You can see where the major players’ agendas will intersect with the main plot and with one another. This is where you control screen time of the supporting cast as their agendas impact the main plot. This is the creative time to identify holes in story logic where set-up or foreshadowing was missed or where extraneous material (usually exposition) can be eliminated.

SCREENPLAY CHARACTERS ARE DIFFERNT

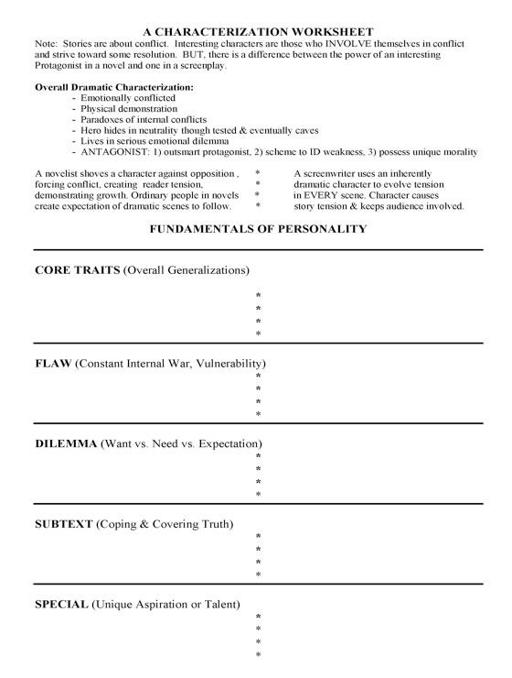

Many new screenwriters get caught in the mental hassle of trying to let go of character detail in a screenplay. Here is a dramatic character worksheet that will help you shift from a novelist’s all-encompassing mindset to a succinct screenwriting view of what kind of characters are needed in a film’s cast. It is important that you understand that those characters you want up on that screen must be

inherently dramatic

. Their attitude, tone, habits, demeanor create a change when they walk into a room. They are the Alpha people of the world who make things happen by reacting visually and powerfully to the circumstance, dialogue, people they encounter. Cinematic characters are never boring or common. The audience expects them to be vividly interesting.

On the Character Worksheet, look closely at the differences between characterizing for a novel and characterizing for a screenplay. The major factor is that in a novel the writer has the time and luxury of evolving a character’s growth through internalized consideration of experiences. The novel’s characters learn and grow at a more gradual pace. The protagonists and antagonists in screenplays have to be inherent trouble-makers or movers-and-shakers. Their essential personality factors make things happen from Page 1. Their learning and growth curves are steeper and more intense in the visual “Now” of the cinematic story with minimal–if any–thinking down-time. Thoughts cannot be seen on the screen and the tool of Voice Over gets tiresome. Watching a character think for longer than a flicker of seconds is boring for the audience. Cinematic characters are action-oriented because actions are visual.

These characters make things happen in every scene, whereas the novelistic characters tend more to evaluate and consider events before, during and after they happen. Thus character depiction in novels ebbs and flows like the ocean tides, but in screenplays they crash and roil like flood waters.

PROFILING CONCLUSION

A character profile empowers the writer with consistency, complexity, individuality, and the ability to credibly exaggerate. Such documentation provides a reference of background and personal data that allows the audience to empathize with the character’s motivation, connect by identifying with their experiences, and live vicariously with that character. Delving into the character’s psychological realms of self-awareness and normal vs. abnormal responses gives the writer a dimension that defies stereotyping. Transferring this data into character action and dialogue as a story unfolds is the ultimate in writing ecstasy! You create such well-thought out fictional characters and your script will demand to be read because these people are so dynamic, so fascinating, they beg to be brought to life on the screen.

The writer’s character profile has zero relationship to an actor’s profiling of that character. Well-trained actors need to evolve their own insights so they can “feel” a character and get “into the skin” of the character. If you mention you have a completed profile, they may ask for it, but most rely on their own gut instincts. That’s why they are actors. Actors act, writers write.

APPENDIX B

From Chapter 2 of

Intro to Screenwriting

:

THE MOVIE PARADIGM

Though in use for a couple of decades before him, Syd Field explained the movie paradigm and proposed it as a schematic outline of the cinematic story in his Screenplay: Foundations of

Screenwriting

. Ever since Field made it popular, working writers have avidly adopted the paradigm’s concepts. The basics apply equally to short stories and novels. The 3-Act structure just makes sense. Aristotle was right. Beginning-Middle-Ending.

Go back over print stories you feel work. Look for the opening hook or introductory scene. Move next to the end of Act I to identify an event that demanded the main character / protagonist change, a happening Field calls Plot Point I. Search about half-way through the story for the Mid-Point Epiphany event that focused the story’s Point-of-View character. Skim forward from there to the material around 75% into the story and find that “Dark Moment” or Field’s Plot Point II that had the main character cowering in defeat. Intentionally or through the “Collective Unconscious,” the majority of the storytellers utilize the structure. Hint: As you read to find these points, you will also be able to identify when events were weak and ineffective, thus causing a story’s disappointment.

Consider the Paradigm Form here that includes some additions to the fundamentals. You will find the lines for the most important Subplots across the lower portion of the form and the story’s time line at the very bottom. At the top are Title and Length. Projecting length of any project allows you to guesstimate the page lengths of each act, thus the pacing of the chain of events leading up to the various signpost events. This schematic will identify approximately how many pages you will need to write to cover all the essential story points.

Of course, each story must have its log line (Story Line on the form). The Statement of Purpose is there to keep the writer focused on the point of the story. Additions to the basics include the fine-tuning of the Inciting Incident in Act I that leads the protagonist to that life-changing Plot Point I and Field’s Act II pinches. Pinch I confronts or gives a glimpse of the greatest fear in the middle of first half of Act II. Pinch II depicts an event that is the worthiness / acknowledgement by others in the middle of second half of Act II.

Use this form to identify the progressive logic of Act II. “This event caused this to happen which caused this . . . .” After the protagonist’s life was spun 180-degrees by the Plot Point I event, the protagonist must learn how to live differently. That means reacting to unfamiliar experiences, learning about new areas of life, meeting new people who challenge the protagonist in new ways. Those are all relative to the “New Life.” Encountered in Act II.

After the Mid-point Epiphany event, the protagonist relishes a higher level of awareness and intensity about his / her role and skills in this life. The meaning and value of the new life is accepted. He or she drives confidently toward achieving the ultimate goal. Thus the second half of Act II is about taking control, a cycle of action rather than reaction. That growth in confidence and focus leads directly to an aura of over-confidence or almost euphoria. In turn, that sets up the protagonist for the antagonist’s assault and take-down at Plot Point II’s Dark Moment.

Act III is the Resolution of all that has gone before. Evaluation of that final one-fourth of the story provides vital guidelines for developing the concluding action of the script. Plot Point II has catapulted the highly motivated-to-survive protagonist into action. He / She has come out of that denigrating experience, determined to fight and motivated to overcome whatever. Preparation has to be made for the climactic battle. That preparation increases the audience’s concern for the character’s chances of success.