Roosevelt (66 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

But how was he to get the evasive Stalin to rendezvous? He hit on the idea of emphasizing the importance of his invitation by sending it by a prestigious courier, former Ambassador Joseph Davies, an old favorite with the Kremlin. The letter was carefully composed. He wanted to get away, the President told Stalin, from a big staff conference and the red tape of diplomatic conversation. Therefore “the simplest and most practical method” would be a brief, informal meeting during the coming summer. Where? Africa was too hot, Khartoum was on British territory, and Iceland—“quite frankly,” there it would be “difficult not to invite Prime Minister Churchill at the same time.” So he proposed either his side or Stalin’s side of the Bering Strait. He would take only Hopkins, an interpreter, and a stenographer. He sought no official agreements or declarations—just a meeting of minds.

While Davies flew east to Moscow with the invitation, Churchill and his party were steaming west across the Atlantic on the

Queen Mary.

The liner had been converted into a troopship big enough to carry an American division of 15,000 men; she was fast enough to evade and outrun U-boats. On this trip she was carrying several thousand German prisoners of war, and also some lice picked up on an earlier trip to southern waters. The Germans were sealed off from the VIP’s on the top deck, but the bugs were not, and they made life miserable for some of the lower echelon of the upper echelon. But Churchill and his military chiefs were unscathed; day after day, as before, they met, adjusted differences, and prepared a united front for the Washington conference. Churchill warned his soldiers not to appear too keen on any one plan at the conference, for it would simply arouse competing proposals, owing to the “natural contrariness of allies.”

Alerted that this formidable task force was bearing down on them, the American chiefs and their staffs resolved that this time they would not be overborne by superior numbers, unity, and staff work, as they felt they had been at Casablanca and earlier conferences. They hoped especially to end the step-by-step opportunism of the past and press on the British a long-term strategy. Preparations were feverish along Constitution Avenue and in the Pentagon, and lines seemed well drawn when Churchill, Dill, Brooke, Pound, Portal, and Ismay held their first meeting with Roosevelt, his Joint Chiefs, and Hopkins in the President’s study on May 12. Roosevelt, after gracefully noting the triumphant progress since the last dismal meeting in the White House less than a year before, declared that while it would be desirable to knock Italy out of the war after the

battle for Sicily, he shrank from the thought of putting large armies into that country. He favored a strong build-up for a cross-channel attack in the spring of 1944.

Churchill replied for his side. He spoke feelingly of Roosevelt’s generosity, at the last White House meeting, when the crushing news of Tobruk’s fall had come in. His Majesty’s government, he emphasized, stood by the plan for the cross-channel attack, which could come in the spring of 1944 at the earliest, but what in the meantime? Hundreds of thousands of men could not stand idle in the Mediterranean. A strong blow at Italy might knock it out of the war, relieve Russia by forcing Hitler to divert troops from the Eastern Front to replace Italian troops withdrawn from the Balkans, nudge Turkey toward active participation, and allow the seizure of ports and bases necessary for launching assaults against the Balkans and southern Europe.

It was the same old difference of emphasis, timing, and priority. Day after day the Combined Chiefs of Staff met, argued, and adjourned. Marshall, with Roosevelt’s backing, was adamant. He feared that once again the suction effect of the Mediterranean would drain away troops and supply and jeopardize cross-channel plans. King was still pressing for more effort in the Pacific, especially if the British were to have their way in the Mediterranean. Paradoxically, each side felt that the other was undercutting the cross-channel attack—that the British were doing so by diverting to the Mediterranean, the Americans by stressing the Pacific. The British were adamantly against a “premature” cross-channel invasion, with its risk of spilling oceans of blood; the Americans had resolved to resist their ally’s strategy of “scatteration” and “periphery-pecking” in the Mediterranean.

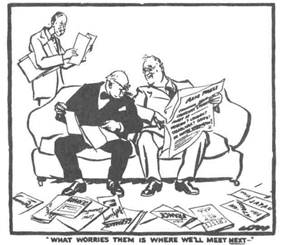

May 14, 1943, © Low, reprinted by permission of

The Manchester Guardian

© Low, world copyright reserved, reprinted by permission of the Trustees of Sir David Low’s Estate and Lady Madeline Low

The result was a standoff. The British agreed, as first priority, to help mount a “decisive invasion of the Axis citadel,” with a target date of May 1, 1944; they also approved an escalating bomber offensive to disrupt and destroy the German military and industrial system and break down the morale of the German people. An emergency cross-channel operation—the old plan named

SLEDGE-HAMMER—

was kept on the books in case of sudden need. In exchange the President and his chiefs agreed to plan further operations in the Mediterranean to knock Italy out of the war. To counter the suction effect, a limit was put on Allied troop strength for the attack on Italy, and seven divisions were slated to be transferred from the Mediterranean to Britain, starting in the fall, to help the build-up there. But Eisenhower would still have twenty-seven divisions in the Mediterranean

At last a date had been fixed, a rough order of priorities set. Even so, the Americans were uneasy. Churchill did not seem wholly reconciled. And what about Stalin? From his view the only important result of the conference would be wholly negative—postponing a cross-channel invasion until May 1944. Stalin had been furious after the news from Casablanca that the attack had been

postponed from spring 1943 to August or September. What would he say now?

This was the question assailing Roosevelt and Churchill as the conference ended. Grimly they sat down together to prepare a letter to their comrade in arms. Hour after hour they wrote and rewrote, sending scrawled passages out to be typed, and then scribbling over the drafts until they were almost illegible. Two of the most gifted expositors in the world at this moment were reduced to stammering schoolboys making a confession. At two in the morning, to Roosevelt’s relief, Churchill offered to take the latest draft away with him and “tidy it up” and return it. Both Churchill and Marshall were leaving for Algiers to consult with Eisenhower; Roosevelt agreed that the Chief of Staff could fly with the Prime Minister and work on the statement.

Next day, on the flying boat over the Atlantic, Marshall took the tattered drafts and in two hours wrote a message that aroused Churchill’s admiration for its clarity and comprehensiveness. He and Roosevelt approved it unchanged. The President held the message for a week before sending it, signed only by himself. Mostly it was a succinct statement of the whole range of Anglo-American global strategy. But almost hidden in the next-to-last paragraph was the fateful sentence: “Under the present plans, there should be a sufficiently large concentration of men and material in the British Isles in the spring of 1944 to permit a full-scale invasion of the continent at that time….”

By now Davies had returned to Washington with a hopeful report on his meeting with Stalin. Things had started awkwardly, he told the President, who listened eagerly and demanded specifics about Stalin and his comments. Stalin had bluntly reiterated that he could accept neither the African invasion nor the air attack on Germany as equivalent to the second front. He was suspicious of the Americans as well as the British. When Davies urged that if he and Roosevelt met face to face they could together win the war and the peace, Stalin replied tersely, “I am not so sure.” It took Davies a long time, he told Roosevelt, to penetrate the suspicion and near-hostility. But he had come back bearing a favorable response to Roosevelt’s invitation. Stalin was willing to confer with the President in Fairbanks in July or August.

Roosevelt was elated, but he was apprehensive, too. He had told Stalin about the postponement of cross-channel plans only after Davies had returned. What would Stalin say now? He had not long to wait. “Thank you for the information,” Stalin wrote on June 11, in reply to the Roosevelt-Churchill-Marshall message. He then listed item by item all the Anglo-American promises of a second front in 1943. Need he speak of the disheartening impression that this fresh

postponement of the second front would produce both among the people and among the Army? The Soviet government could not align itself with this decision—which had been adopted without its participation. Stalin said nothing about the plan to meet in Fairbanks.

Roosevelt now faced a crisis in Soviet-American relations not only over the second front, but also over Poland. Stalin had always been cold toward the Polish government-in-exile in London, headed by General Wladyslaw Sikorski, whom the Kremlin viewed as a bourgeois moderate surrounded by reactionaries and militarists. The Poles had repeatedly appealed to the President on the issue of the 1939 Polish-Soviet boundaries, established when the Russians and the Germans carved up Poland, and on Soviet treatment of Polish nationalists. The President, eager to promote unity within the United Nations camp but always sensitive to the big Polish voting groups at home, had tried to conciliate the London Poles while evading the central issue. On one point he was insistent: there must be no discussion of the Polish-Soviet boundary issue until a later time.

Relations between the Kremlin and the Polish government deteriorated during early 1943 and collapsed in April, with a big assist from the Germans. Goebbels’s propagandists suddenly announced that in the Katyn Forest, near Smolensk, there had been found the bodies of thousands of Polish officers shot by the Bolsheviks three years earlier. “Revolting and slanderous fabrications,” the Russians charged; the Nazis themselves had committed the monstrous crime. At this point the London Poles, who had always suspected that the Russians were guilty, asked the Red Cross to make an investigation on the spot. Furious over this “collusion” with the Nazis, Moscow broke off relations with Sikorski’s government. Stalin so informed Roosevelt.

The President asked Stalin to define his action as a “suspension of conversation” with the Poles rather than a complete severance of diplomatic relations. He doubted that Sikorski had collaborated in any way with the Hitler gangsters but granted that the London Poles had erred in appealing to the Red Cross. “Incidentally,” he reminded Stalin, “I have several million Poles in the United States….”

Stalin was unmoved. By now he was seething at his allies. His grievances were many and painful. They had broken off the convoys. They had got bogged down in Africa and let the Red Army take the brunt of the winter fighting. They had never accepted the Polish-Soviet frontier of 1939. They had not broken with Finland. The Soviet government, he felt, had made concession after concession, gesture after gesture. Had he not responded to

Anglo-American wishes in dissolving the Comintern, even though he had sworn on Lenin’s tomb never to abandon the cause—Lenin’s cause—of world revolution?

And still no second front. To Stalin this was not a question of strategy alone. The blood of his people was at stake. Hundreds of thousands of Russians would perish because the Anglo-Americans would invade Europe in 1944 instead of 1943 or 1942. Millions of civilians would be left that much longer to suffer and die under the Hitlerites. Roosevelt worried about his Poles, but Stalin, too, had a kind of public opinion to consider. The bereaved Soviet families, the millions under Nazi rule, the maimed soldiers—what would they think about Stalin’s repeated assurances that the Anglo-Americans were coming? The Marshal—for Stalin had assumed that title during the commemoration of Stalingrad—must have reflected on the seeming obtuseness of the Anglo-Americans about the Soviet need for security on the western borders. For centuries Germans, Poles, Swedes, and others had pillaged their way eastward into Russia across the open plains. From the very start of the war—indeed, during the most desperate weeks in late 1941—Stalin had forthrightly insisted on a western border that would give his nation security. Roosevelt had not responded. In short, the Anglo-Americans would not provide real collective security through a United Nations second front, but neither would they support his efforts to gain security through unilateral action. Were the British hoping that Russians and Germans would exhaust themselves in mortal combat? Was that why they had been so deceitful about when the second front would come? Were they trying to help Russia just enough to keep it in the war, but not so much as to help that country win it? Did they hope that after the war they could pursue the old imperialistic policy of fencing Russia in? Could they even be plotting a separate peace? As long as they delayed the second front they could use it as a threat against Hitler, or as a way of bargaining with him—or his generals—for not attacking. All these dark suspicions must have smoldered in Stalin’s conspiratorial mind. He ordered Maisky home from London and Litvinov from Washington. And he cabled to Roosevelt that he could not meet with him.