Roosevelt (30 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

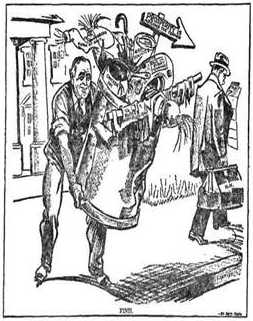

March 3, 1933, Jerry Doyle, Philadelphia

Record

In the White House—now a command post to handle economic crisis—sat the new President, unruffled and smiling. His own account of his busy first day and its crucial decisions he set down in his diary (which he kept two days and then abandoned). After attending church with his whole family and lunching with family and friends, he plunged into a round of meetings. “Two-thirty P.M. meeting in Oval Room with all members of Cabinet, Vice-President and Speaker Rainey, outlining banking situation. Unanimous approval for Special Session of Congress Thursday, March ninth. Proclamation for this prepared and sent. This was followed by conferences with Senator Glass, Hiram Johnson, Joe Robinson and Congressmen Steagall and Byrnes and Minority Leader Snell— all in accord. Secretary Woodin reported bankers’ representatives much at sea as to what to do. Concluded that forty-eight different methods of handling banking situation impossible. Attorney General Cummings reported favorably on power to act under 1917 law, giving President power to license, regulate, etc., export, hoarding, earmarking of gold or currency. Based on this opinion and on emergency decided on Proclamation declaring banking holiday.… Hurried supper before Franklin, Jr., and John returned to school. Talked with Professor Warren in evening. Talked with representatives of four Press Associations explaining bank holiday Proclamation. Five minute radio address for American Legion at 11.30 p.m. Visit from Secretary of State. Bed.” Such was the breathless course of the President’s first day as he recorded it.

The banking crisis dominated Roosevelt’s whole first week. The President and his advisers sensed that the key problem was one of public psychology. The people wanted action. The President had promised it. The curious fact was that the important actions had already been taken by the states and by the banks themselves: the banks had closed. Roosevelt played his role of crisis leader with such extraordinary skill that his action in

keeping

the banks closed in itself struck the country with the bracing effect of a March wind. His action was essentially defensive, negative, and conservative—but he made of it a call to action. He even deceived the reporters; the President himself complained to them in a press conference that in reporting his extension of the bank holiday they played up the extension rather than the exceptions he was going to make.

Summoned by the new President, Congress convened in special session on Thursday, March 9. While freshman members were still looking for their seats, the two houses hastily organized and received a presidential message asking for legislation to control resumption of banking. The milling representatives could hardly wait to act. By unanimous consent Democratic leaders introduced an emergency banking act to confirm Roosevelt’s proclamation and

to grant him new powers over banking and currency. Completed by the President and his advisers at two o’clock that morning, the bill was still in rough form. But even during the meager forty minutes allotted to the debate, shouts of “Vote! Vote!” echoed from the floor. “The house is burning down,” said Bertrand H. Snell, the Republican floor leader, “and the President of the United States says this is the way to put out the fire.” The House promptly passed the bill without a record vote; the Senate approved it a few hours later; the President signed it by nine o’clock.

Swift and staccato action was needed, Woodin had said. The very next day—March 10—the President sent Congress a surprise message on economy. It was couched in crisis tones. The federal government was on the road to bankruptcy, Roosevelt said. The deficit for the next fiscal year would exceed a billion dollars unless immediate action was taken. “Too often in recent history liberal governments have been wrecked on rocks of loose fiscal policy.” He asked Congress for wide power to effect governmental economies, to trust him to use that power “in a spirit of justice to all.” The proposed bill bore the portentous title “To Maintain the Credit of the United States Government.”

Caught by surprise, lobbyists of the American Legion and other veterans’ organizations wired their state and local bodies that veterans’ benefits were endangered. A deluge of telegrams hit Capitol Hill. Defying organized veterans was a stiff dose for Congress, which again and again during the past decade had passed veterans’ legislation over presidential vetoes. Revolt erupted among the House rank and file, and for a time the Democratic leaders lost control of the situation. A caucus of Democratic representatives almost agreed to an emasculating provision, and adjourned after heated wrangling. On the floor the leaders helped restore discipline through free use of the President’s name.

“When the

Congressional Record

goes to President Roosevelt’s desk in the morning,” one leader warned, “he will look over the roll call we are about to take, and I warn you new Democrats to be careful where your names are found.” The barbed point touched off hisses and groans. Despite the parliamentary powers of the leaders, the bill passed the House only because sixty-nine Republicans crossed the aisle to back the President. Ninety Democrats, including seven party leaders, deserted their new chief in the White House on his second bill. More trouble was brewing in the Senate, as the telegrams from American Legion posts piled up.

But nothing could stem the President’s momentum. On March 12, at the end of his first week, he established direct contact with the people in the first of his “fireside chats.” The President’s reading copy of his talk disappeared just before the talk, but he calmly

took a newspaperman’s mimeographed copy, mashed out a cigarette stub, turned to the microphone, and began simply, “I want to talk for a few minutes with the people of the United States about banking.…” For twenty minutes or so his warm, reassuring voice welled into millions of homes, explaining the banking situation in simple terms without giving the impression of talking down to his listeners. The speech was a brilliant success.

The President stayed on the offensive. The next day, when a divided Senate was to consider the economy bill, he shot a terse seventy-two-word message to Congress on a new subject: beer. He recommended immediate modification of the Volstead Act to legalize the manufacture and sale of beer and light wines; he asked also for substantial taxes on these beverages. The shattered ranks of Democratic congressmen quickly solidified behind this popular move, which had been promised in their national platform. Roosevelt skillfully timed his message for maximum effect. The Senate passed the economy bill on the fifteenth, the beer bill the next day.

A dozen days after the inauguration a move of adulation for Roosevelt was sweeping the country. Over ten thousand telegrams swamped the White House in a single week. Newspaper editorials were paeans of praise. The new President seemed human; he seemed brave; above all, he was acting. A flush of hope swept the nation. Gold was flowing back to financial institutions; banks were reopening without crowds of depositors clamoring for their money; employment and production seemed to be turning upward.

“I will do anything you ask,” a congressman from Iowa wrote the President. “You are my leader.”

But the President did not deceive himself. The efforts so far, he realized, had been essentially defensive. Even with the first three measures through, he told reporters, “we still shall have done nothing on the constructive side, unless you consider the beer bill partially constructive.” Originally he had planned for Congress to adjourn after enacting the first set of bills, then to reassemble when permanent legislation was ready. But why not strike again and again while the mood of the country was so friendly? The leaders were willing to hold Congress in session; a host of presidential advisers were at work in a dozen agencies, in hotel rooms, anywhere they could find a desk, drawing up bills. The result was more of the fast and staccato action that would go down in history as the “Hundred Days.”

March 16—

The President asked for an agriculture bill to raise farmers’ purchasing power, relieve the pressure of farm mortgages, and increase the value of farm loans made by banks. Hastily framed by Secretary Wallace and his aides, the measure was based partly on recommendations of a conference of farm leaders. It was the most dramatic and far-reaching farm bill ever proposed in peacetime, the President said later. The House passed the bill by a 315-98 vote on March 22 after five and a half hours of debate, the Senate by an equally lopsided vote five weeks later. In mid-May the President signed the Agricultural Adjustment Act into law.

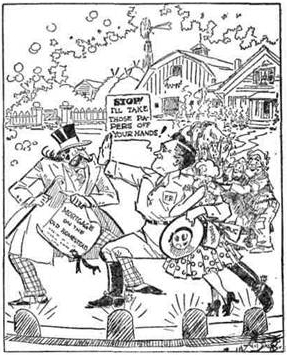

AND SO, AFTER ALL THESE YEARS!, May 17, 1933

Ding Darling, © 1933, New York

Herald Tribune,

Inc.

March

2

1

—The President asked for quick authorization of a civilian conservation corps for the purposes of both reforestation and humanitarianism. This bill interested Roosevelt himself as much as any single measure of the Hundred Days. It was designed to put a quarter of a million young men to work by early summer, building dams, draining marshlands, fighting forest fires, planting trees. Congress pushed the measure through in ten days by voice vote.

March 21—

The President asked for federal grants to the states for direct unemployment relief. His move represented a break with the previous administration’s policy; flatly opposed to giving money to the states for relief, Hoover in the end had grudgingly backed loans to states and cities. Proclaiming that the nation would see to it that no one starved, Roosevelt was prepared to launch the

biggest relief program in history. Congress passed the Federal Emergency Relief Act by heavy majorities and authorized the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to make available five hundred millions through the Federal Emergency Relief Administration.

March 29—

The President asked for federal supervision of traffic in investment securities in interstate commerce. To the old doctrine of

caveat emptor,

he said, must be added the further doctrine, “let the seller beware.” The essential goal was full publicity for new securities to be sold in interstate commerce. In an effort to restore public confidence, heavy penalties would be levied for failure to lodge full and accurate information about securities with the government. The bill passed early in May. Another measure, the Banking bill of 1933, was intended to impose on banks a complete separation from their security affiliates. Early in May the two Houses passed the measure to help drive the money-changers out of the temple.

April 10—

The President asked for legislation to create a Tennessee Valley Authority, charged with the duty of planning for the “proper use, conservation and development of the natural resources of the Tennessee River drainage basin and adjoining territory.…” Roosevelt’s vision was broad: he saw the project as transcending mere power development and entering the wide fields of flood control, soil erosion, afforestation, retirement of marginal lands, industrial distribution and diversification—in short, “national planning for a complete river watershed.…” The measure had a dramatic background: for over a decade George W. Norris of Nebraska and other members of Congress had desperately fought efforts to sell the government-built Muscle Shoals dam and power plant to private interests. They had barely staved off such a sale. Now Roosevelt was urging that Muscle Shoals be but a small part of a vast program that would tie together and invigorate a huge, underdeveloped region. Involving extensive public ownership and control, the measure was almost pure socialism, but Congress passed it by decisive majorities. The President signed the bill May 18, with Senator Norris exultantly looking on.

April 13

—The President asked for legislation to save small home mortgages from foreclosure. With foreclosures rising to a thousand a day, he wanted safeguards thrown around home ownership as a guarantee of social and economic stability. Machinery would be provided through which mortgage debts on small homes could be readjusted at lower interest rates and with provision for postponing interest and principal payments in cases of extreme need. Roosevelt had his legislation within a month.