Roses Under the Miombo Trees (23 page)

Read Roses Under the Miombo Trees Online

Authors: Amanda Parkyn

Into this whirl of activity came Mark's parents for a fortnight's visit, their chance to meet their grand-daughter and for âBoompapa' to see Paul for the first time since he was tiny. The timing also meant they could be there for Caroline's Christening. They arrived bearing toys, baby dresses and even clothes for me. Despite being the opposite of me in build, Mother was brilliant at choosing things that suited me â a welcome talent for a daughter-in-law so far from any clothes shops. Invitations to drinks and dinners came thick and fast; we took them on our only tourist trails â Mpulungu and the Liemba, and the Kalambo Falls â played bridge, and prepared for the Christening party. By dint of much pestering we had persuaded the Archdeacon to visit Abercorn, and on Sunday 12 April, after the 4 p.m. service in the little church decorated with Mother's flower arrangements, about 35 guests and their children came home for tea, cake and champagne cocktails. Standing on our front terrace â the rains having now finished â I felt proud of our new garden with its green lawn and the rose bushes already starting to bloom. Photos show our smart guests glass in hand, all the men in suits, the women in frocks and hats and Jiff, Caroline's godmother, elegant in pale, elbow-length gloves. Someone had indeed iced the cake, for a close-up photo by Pix in Caroline's baby book shows an elaborate riot of roses and trellis patterns in white icing, topped by the stork from Paul's Christening cake. Perhaps it was done by Mrs. Smit, a show prize-winner, whose cake for the 10

th

anniversary celebrations of All Saints' Church had been â

a masterpiece of confectionery bearing on its iced surface a sugar model of the church building, perfectly executed and much admired by everyone'

, as

Abercornucopia

had reported.

With the Cape Town grandparents at Caroline's Christening

Caroline with her Dad at one month

The grandparents' departure left that sad quiet gap that follows any successful visit: Paul missed all the attention, I Mother's practical help and even Boy had got used to regular grooming and walkies. Mark though had to catch up with work after his holiday, and his spirits were low. The relentless pressure of covering a very large sales area, of having to look after numerous visitors (the depot on Lake Tanganyika a constant source of interest), and of feeling he was not being kept up-to-date with company matters were getting him down. And holiday or no, the S.S. Liemba must be met, every other Sunday.

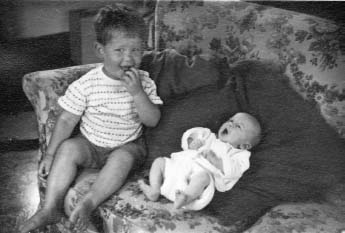

Paul baby-minding

It was at about this time that the Liemba brought another mini-drama to Abercorn: a young girl travelling down from Kigoma turned out to have smallpox. There was an instant alert and Caroline for one had to have her inoculation far earlier than had been planned. I remember Chris Roberts showing us a photo of the child, her impassive face and skinny body a mass of raised pustules. I must have realised how much it would have worried my parents, for â atypically â I discreetly left this news item out of my letters home.

I was now busy with staff training, having sacked Bourdillon in exasperation after some last misdemeanour. Jiff matter-of-factly explained to me that by now I would have a poor reputation with any available local workforce as an impatient “cheeky madam”. Why not, she suggested, train up Uelo, whom I got on with and who was bright enough to learn all I needed? And she and Alan could recommend a piccanin â a young lad I could train up in the garden, who had done some work for them and was keen to learn. It worked a treat; soon Uelo could do â

far more than Bourdillon ever could'

and young Friday was â

a great success in the garden, chasing Paul with the hose while watering, pushing him on his trike and learning to do the endless nappy ironing

'. I remember them both as bright, cheerful lads, always good-tempered and, like Daniel, able to deflect my impatience with reassuring smiles.

We had now been in Abercorn a year, felt settled in the little community, where we had made good friends. How fortunate we were, I think now, to have lived in that small but vivid world at that particular time! We wives and mothers especially, unencumbered by much in the way of domestic chores, could pursue whatever projects we fancied, our children playing together as we socialised. The club, still largely unaffected by the forthcoming prospect of multi-racial membership, flourished. Mark was now chairman of the golf section, playing well and busy organising matches with visiting teams. I was now secretary of the main club and active in the yacht section: with two children I had had to give up any pretence of being a golfer, but with the yacht club's safe play area for children, and friends to keep an eye on Caroline in her carrycot, I now felt I could give free rein to my recently developed passion for sailing. I loved everything about it: the excitement of hanging out by your toes in the teeth of a high wind, pushing the boat to its limits, the rush of activity at âReady about! â lee-o!', the boom swinging over and the scramble to trim the sails. On quieter days, inching the boat along in the lightest of breezes, you had time to chat with your sailing partner, to notice your shoulders burning and wish you had put on a shirt over your bikini, to hear other voices across the water, a snatch of a Bob Dylan song

blowing in the wind

perhaps, or a burst of laughter. I surprised myself with my competitive streak, the low cunning I could employ to steal another boat's wind when the breeze died. Competitive sailing took place on Sundays, so that Mark missed every alternate one, but at the club we minded each others' children, took turns to skipper and crew, the wives to produce lunch. As well as couples with young families there were also agreeable bachelors about, including smiling Colin Carlin who always seemed to be around, ready as a sailing partner or to lend the little boat he had built. To have the little lake, spring-fed and free from the liver fluke that caused the debilitating disease bilharzia, to have the use of the dinghies, Enterprises and Graduates mostly, free with club membership â what extraordinary good fortune! (Much later I watched sailing on an English midlands reservoir, saw how cold it was, learned how expensive, and sensed that my sailing days were over). There was the on-going fun of a social life with a wide variety of friends, mostly our age with young families. (I say âvariety', but of course all of them were white â European, as we called ourselves, although many had never lived in Europe, or not for decades.) Life, at least on the surface, was busy and enjoyable.

Fun, busy, enjoyable â yes, life was all of those things, but as in any marriage other factors were also in play. There were the pressures of Mark's job, which not only took him away so much, but was also far from head office and which became increasingly burdensome to him. I felt sympathetic but helpless as he complained about the lack of support, and how this meant he had to be always sending telegrams, phoning (not easy, lines were often down) and even writing â never his strong suit. At the same time we were frequently inundated with visitors and the need to entertain them. I can see now the resulting stress affected our respective health in different ways.

Hon. Sec. Abercorn Club, photo courtesy Horizon magazine, where it was captioned:

Amanda L â, secretary of Abercorn Club, and leading member of its yacht section, believes

that Abercorn has it all. âYou just cannot be bored here' she says.

Mark could not sleep and was â

drinking more than is good for him'

as I put it in a letter home. Fortunately our doctor, Chris, managed to convince him to cut down his drinking, and to get exercise, but Mark would not allow him to request the company to let him have sick leave, which would certainly have led to a black mark on his file. I meanwhile was coping with the unwelcome re-emergence of my âbad back' problem â a traumatic development for me, given the surgery I had had aged 19, and my memories of the way it had put my life on hold. It first âwent' while Mark was on a 10 day stint at Head Office on a course

(âtoo much lifting while he was away â no more lifting ever again'

, I wrote, unrealistically.) At first I tried a borrowed infrared lamp for strained sacro-iliac muscles. As the pain became more acute Chris offered me bed rest, which I felt was impossible, or a plaster cast to keep me from bending. This last proved both uncomfortable and entirely ineffective. There were of course no local services like physiotherapy, no Pilates exercise classes or chiropractic, which have helped me so much in recent years. Eventually, and distinctly unwillingly, the company agreed to arrange for me to see the only orthopaedic surgeon of any repute, who was down in Salisbury â a lengthy trip which would have meant leaving the children for some days. I postponed this, hobbled along trying unsuccessfully to do less, finally managing to order by mail from the Copper Belt a support corset, which helped enough for me to decide not to press for the Salisbury trip. I learned, many years later, the extent to which my back could âgo' as an expression of my need for greater support somewhere in my life. Then of course I was just a young wife and mum worrying about my husband, determined to keep things going at home and, being me, wanting to be part of whatever was going on in the community.

Â

Woman's Own, 1964

The oven's on as low as it will go,

children asleep. She glances at her watch.

Soon surely? She flips a magazine.

In between

The Perfect Pedicure

and

Casseroles for Chilly Days

, she's drifted

to Kensington, the basement flat she shared

with friends. They'd window shop the Brompton Road,

full skirts swishing over net petticoats,

in short white gloves. They'd pass around the latest

hags' mags, Woman's Own or Woman, read

them on the tube. Last thing she'd settle in

with the short stories, four per issue, lost

in fragile love first glimpsed as pulses raced,

in heart stopping quarrels and misunderstandings,

chewing a nail until at last a head

could rest on a tweedy shoulder. Better yet,