Roses Under the Miombo Trees (7 page)

Read Roses Under the Miombo Trees Online

Authors: Amanda Parkyn

The closer Christmas got, the more I missed all the traditions of our large family get-togethers in dead of winter, the piles of presents that mounted on the big table on the landing, the dog-eared but much loved decorations we strung across the hall, the appearance of spare uncles and aunts, so that by the day itself we might easily be ten or more for Mum to cater for. Perversely I even started to miss the chill of a dark English winter day. Here in the hot sun that appeared between downpours, it felt ridiculous to be sweating over the stirring of a heavy Christmas pudding, or icing a fruit cake, though I did, unsure what to replace them with. I became set on making our first married Christmas as social as we could, and in an effort to settle in to the local community, we invited to drinks not only the few couples we could now call friends, but also some we hardly knew at all. Mark made an enormous and powerful wine cup, I laid on the nibbles â and alas, most of them simply did not come, citing when I phoned them vague and unconvincing excuses. I felt mortified, my pain more acute from having learned at boarding school the importance of being popular and in the thick of things, to stave off homesickness and isolation. Now, instead, I felt more lonely than ever. Of course in my letter home I didn't mention my feelings at all, just that the cup put the remaining few of us âswiftly on our ears' and that after a huge scrambled egg at 9 we sent them reeling off into the night.

No health warnings for pregnant women in those days: I happily drank as much as everyone else â which was, by today's standards, quite heavily. Both beer â the local Castle and Lion lagers â and wine and spirits from South Africa were cheap. My favourite sundowner was brandy and ginger ale. Similarly, cigarettes cost little, made of course from local tobacco and all tasting much the same. We favoured State Express as being classier than Gold Leaf or Pall Mall, at around 1/10d for 30. At the budget end, for the African market, came Star at 2d. for eight.

The airmail service was surprisingly speedy in those days, and my letter wishing the family a happy Christmas was written on Sunday 17 December and posted next day:

I am sure you can easily believe that we would love to be there too, in fact were only saying so in wistful tones at breakfast this morning. Everyone here gets very homesick for snow, log fires and so on â carefully leaving out the smog and drizzle. We shall either boil and wish we could have fruit salad instead of plum pudding if only it didn't feel wrong, or be trapped by tropical downpours and wonder if we could manage at least the log fire bit after all.

In the event I need not have worried about loneliness, my post-Christmas letter giving a full account of our packed programme. We made the best we could of our limited budget, decorating the house with a small conifer felled from a vacant neighbouring plot and triumphantly conjuring homemade decorations for 10/-. We had also begun to get involved in Gwelo's only Anglican church â we were both regular churchgoers then. It was an anchor of sorts in a new place, a way of entering the local community, and apart from the fact that the building was new, modern and light, felt little different to worship in from the parish church at home. I don't recall ever seeing a black face in the congregation. After much discussion about the risk of my fainting during a service, we opted to avoid the heat and go to Christmas Eve midnight mass (I sitting throughout near the door) â a wise decision as it turned out, because Christmas Day dawned cloudless and exceptionally hot. We opened the mountain of bulgy brown paper parcels with their green customs labels I had studiously avoided reading. Baby clothes mainly, for me, and a fine edition of Jane Austen's

Persuasion

from Pa, which I have to this day. There were records â LP's â of much missed classical music, a silk tie for Mark, and my mother, typically, had even remembered Daniel:

Daniel was thrilled with the shirt you sent, he said we must write and thank you but I am hoping to get him to write tonight, to enclose with this. We gave him a pair of brown canvas shoes and yellow socks which pleased him too. I don't think Christmas meant an awful lot to him, but he slaved on Christmas Day and then had all Boxing Day off, so was quite happy.

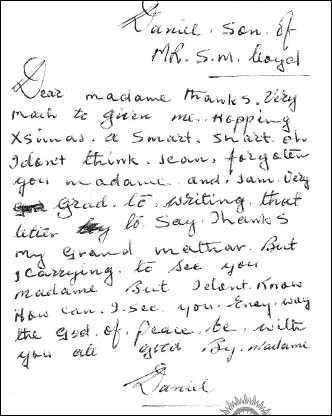

He did indeed manage the letter, respectfully written on a sheet of company notepad: [see next page].

(The expression âsmart shart' remained an affectionately remembered expression in my parents' household for years.)

It was not surprising that the limited education Daniel had received, and of which he was very proud, had been at a mission school. Successive white administrations had not considered educating the native to be a priority and had left it where it had started â with the missionaries. It took nearly 50 years for Rhodesia's administration to open the first state primary school for black children in 1944, followed four years later by the first secondary school. By 1950, according to Lord Blake's

A History of Rhodesia

, there were 12 government schools, compared to 2,232 mission and independent schools. Gradually this number grew; however, it was not until after independence that vocational colleges, polytechnics and other higher education establishments were developed in any number, to meet the great hunger for education, and the demands of industry for commercial and industrial qualifications.

By mid-morning on our first Christmas Day, I wrote home later, we were at one couple's for morning tea, another's for a cold lunch, and in the evening

after a siesta, Mark and I began preparing the dinner, which was quite a labour. We had turkey, ham and all the trimmings, with iced Vichyssoise first, and plum pudding with Mark's knockout brandy butter after â a goodly evening with Fran and Doug, complete with cigars and liqueurs

. On Boxing Day we felt âslightly decayed' but four other guests came for morning tea, the men ending up playing cricket on the hard-baked lawn. By evening we were celebrating the first rain for weeks, as we went out to another couple's buffet supper.

It is a wonder all this did not bring me into labour, but it didn't. The post-Christmas anti-climax came and I felt huge and clumsy, especially in the heat. Naively I believed that my baby, officially due on 1 January, would arrive on time, but âBert', as s/he was nicknamed, stayed comfortably put. I became increasingly impatient, not convinced that this pregnancy would ever end. In search of a change of scene, we took to going for drives:

a lovely drive to Selukwe in the afternoon, where there is a sudden change to quite spectacular scenery. It isn't really a great treat for Mark to go driving at weekends, but I hadn't seen anything round here except Gwelo itself â most of the roads are so bad he won't take me anyway at the moment

.

It is time I explained about the roads. Around town, and on the main road between Bulawayo and Salisbury, you could rely on a fair width of tarmac. Elsewhere it was very different, as my cousin John Watson, working for Dunlop in the Central African Federation at the time, remembers:

âThe roads were of several types. The most basic was simply a clearing through the bush and, as the weather was mainly dry, the surface was dust which got everywhere, up your nose, into your hair and clothes. Most frustrating was to get behind a slow lorry which simply condemned you to driving in a dust storm. To take a chance and overtake was to drive into the unknown and for many an impatient soul this was the very last thing they did. The next type of road was the âstrips'. These were narrow strips of tar, set apart approximately the width of a vehicle's wheels. If nothing was coming, you were fairly comfortable, but when another car came in sight you had to get the nearside wheels off into the dust on the left. This was often quite a hazardous procedure, but the Dunlop service engineer boasted that he had experimented with differential tyre pressures and could go on and off the strips at 80 mph (the speed limit was 50 mph). Next, there were the nine foot tar roads and now and then you could find the luxury of a road where two cars could actually pass one another without driving into the dust.'

He goes on to mention his â

brand new beige Wolseley 6/90, no mean barouche, well able to do the ton on the excellent stretch of new road south of Northern Rhodesia's Copperbelt

'. Later on, as he settled in, he could polish off the 200 miles in under three hours, to the astonishment of his friends at the Ndola Club.

In the midlands, things were slower: on the dirt roads we would pray for a road grader to have recently passed by, smoothing out the bone-shaking corrugations that had built up. Otherwise you had to try to achieve a speed that took your wheels surfing over the tops of them, to ease the ride. Mark's larger company Ford Zephyr had a better chance of this than our little old Morris Minor. Another real hazard was the open railway level crossings, with nothing but the engine's wail to warn you of an oncoming train â another frequent source of fatal accidents. It is no wonder that I used to worry whenever Mark was âon the road'.

A strip road (with hitch hiker)

Â

Eleven Spoons

On the sideboard, the canteen sits foursquare.

Silver forks and spoons nestle, each in its green baize bed, knives in the lid. Daniel polishes them