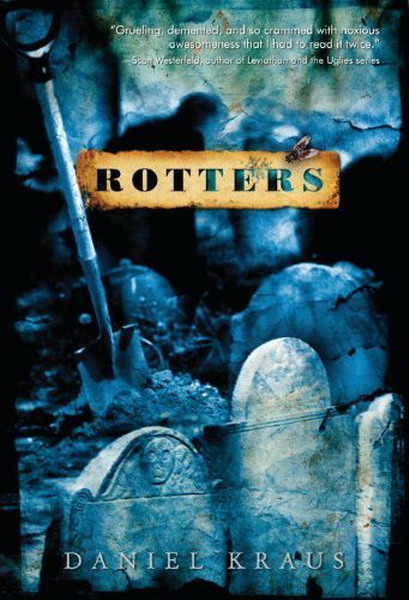

Rotters

Authors: Daniel Kraus

Also by Daniel Kraus

The Monster Variations

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Delacorte Press, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Delacorte Press is a registered trademark and the colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web!

www.randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools,

visit us at

www.randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kraus, Daniel.

Rotters / by Daniel Kraus. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: Sixteen-year-old Joey’s life takes a very strange turn when his mother’s tragic death forces him to move from Chicago to rural Iowa with the father he has never known, and who is the town pariah, although no one imagines the macabre way in which his father earns a living.

eISBN: 978-0-375-89558-6 [1. Fathers and sons—Fiction. 2. Moving,

Household—Fiction. 3. Bullying—Fiction. 4. High schools—Fiction. 5. Schools—

Fiction. 6. Recluses—Fiction. 7. Grave robbing—Fiction. 8. Iowa—Fiction.]

I. Title.

PZ7.K8672 Rot 2011 [Fic]—dc22 2010005174

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

for Amanda

My tale was not one to announce publicly; its astonishing horror would be looked upon as madness by the vulgar.

—M

ARY

S

HELLEY

,

Frankenstein

He who digs a pit will fall into it.

—P

ROVERBS 26:27

T

his is the day my mother dies. I can taste it right off: salt on my lips, dried air, the AC having never been switched on because she died from heart failure while reclining in front of the television, sweating in her underwear, her last thought that she needed to turn on the air because poor Joey must be roasting in his bedroom. Pulmonary embolism: it is what killed everyone on her side of the family and now it has killed her, while I slept, and this salt is the bitter taste of her goodbye.

Turns out, her heart is not what got her. There are her usual morning noises. The apartment door unbolts and unlocks. I kneel on my bed to look out the window. The dawn is piss yellow but beautiful because it is another day and she is alive, and I am alive, and the city around us is screaming with life. Birds push one another along branches, their alien feet peeling bark. There is an empty birdhouse; I hear my mother’s utilitarian humming and realize that she is somewhere beneath it, and that as the birds battle they will bother the string that straps birdhouse to branch, causing it to fall. Given the right trajectory it can kill her and will. I built that birdhouse. It is my fault. This is the day she dies.

I’m standing on the bed now. The birdhouse rights itself. My mother is still alive; I catch sight of her confident shadow

darting around the corner of the apartment complex, her direction indicating the building’s laundry room and the homeless murderer crouching behind the row of washers. Since childhood I’ve watched her claws flash at the barest hints of danger; she has nearly attacked strangers whose only crimes were giving me disapproving looks. Now she is the one in danger and yet I display none of her courage: I let her die. My failure is too much to bear. I bolt up the stairs and into the shower to hide the tears. I love her too much, I know this. I’m a teenage boy and it’s embarrassing. Her constant, hovering, demanding presence should irritate and infuriate me, but it doesn’t. She’s stronger than I could ever hope to be. She’s all I have, and even if that’s her fault I love her anyway, especially today, the day that will turn out to be her last.

Then I hear her noises again; she’s back inside and there is something unwelcome playing on the stereo—she has turned it on now that I am awake and suddenly I remember the vase. Oh, god. Her birthday was two days ago and I bought her stupid flowers at Jewel and, on impulse, a silver helium balloon with some crap about turning forty. The balloon’s ribbon was tied around a vase. Our apartment, cluttered with enough nonperishables to outlast a nuclear winter, photos of the two of us in various Chicago locales, other evidence of a life spent isolated from the wider world, has forced my mother to put the vase on top of the stereo. In moments she will reach to skip the CD’s second track—we hate the second track—and her knuckles will bump the vase and the balloon will pitch and rise. The vase will overturn and spill and there will be water in the stereo, through the wiring, down the wall, and into the power strip. She will reach in there to wipe it up and will die the way she warned me against incessantly when I was little. Electricity takes her.

Or not. She barges into the bathroom, burdened with freshly dried towels, singing along grimly to the loathed second track. Her voice is loud, and then there is the rattle of water to contend with, and I wait for a gap of silence during which I can implore her to turn back from certain doom, but she is already ranting that I get up too early, wasn’t I up all night playing video games with Boris, and how do I survive on so few hours of sleep—all this despite the fact that she is the lifelong insomniac, the lifelong paranoid, not I. What do you want for breakfast, she asks. I don’t care, I say through a mouthful of water—how about eggs. There is a leak in the tub and she will slip in the puddle and strike her head on the edge of the toilet—at least this death is quick—and the final thing I will tell her is not how much I owe her, not how much I need her. It is

eggs

.

She’s tough, so tough: I find her alive and well in the kitchen, curls arranged sloppily, cheeks freckled, shoulders pink, wearing a tank top and cutoffs and red flip-flops, hunched bored in front of a frying pan. It’s all for me, this tedious routine. She could’ve been a nuclear physicist, a powerhouse attorney, a mountaineer. Her intelligence and ingenuity are proven on a daily basis—she knows all the

Jeopardy!

answers, can disassemble and reconstruct a toaster oven in under five minutes, is steely in the face of injuries, crafty in the face of collection agencies—yet for me she accepts the indignities of raising an ungrateful sixteen-year-old, the stultifying grind of an insulting desk job. Despite these sacrifices, I won’t eat. How can I? The room twitches with menace. Grease pops in the pan; it will burn holes in her ever-watchful eyes and she will flail, and I do not have to list the number of sharp objects waiting for her on the counter.

I choke down the eggs. I watch her as she cleans up. She

raises the edge of her cutoffs to brood over cellulite. Contorted in this way I can see the unnatural groove that passes through the curvatures of her left ear. It is a wound she suffered from my father. I don’t know my father and she has offered neither information nor emotion. The injury is part of a puzzle I’ve been too self-absorbed to wonder about, the true origin of her sleepless nights. The pitiful little I know is this: to draw attention away from the disfigurement, she stretches her lobes with extravagant earrings; those she wears now are turquoise with mini-dangles that swirl and catch themselves in knots. So

this

is how she dies. Today’s chores include mowing the grass along the building’s front lawn (for a few bucks off our rent), changing the oil in the car, and cleaning dust from fans that over the summer have caked. It seems inconceivable that such trifling devices could take down my invincible guardian, but they will. Mower, car, fan: each has spinning components that will snatch dangling earrings, gears that will pinch the skin, then shudder against live meat before self-lubricating with blood. I have time to disable only one device, and the choice immobilizes me.