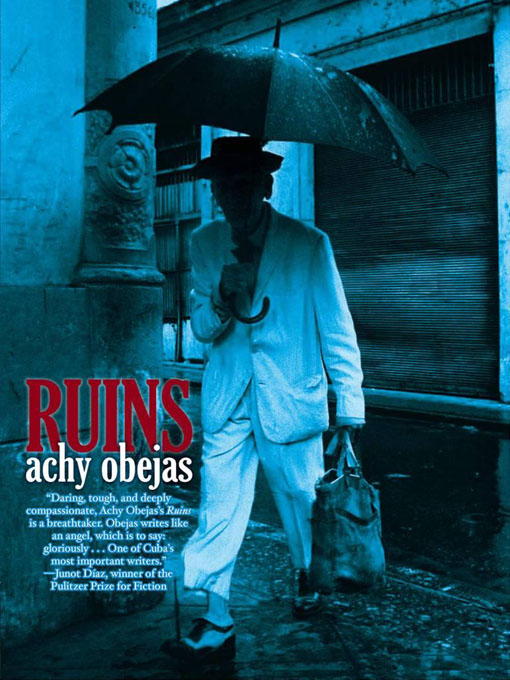

Ruins

More Critical Praise for Achy Obejas

for

Days of Awe

“Obejas masterfully links identity with place, language, and the erotic life, without ever descending into sentimentality … Her descriptions render her characters’ emotional lives with a precision that precludes exotic stereotyping. [A] focus on language accounts for one of the novel’s most enchanting riches, revealing a capacity to neatly articulate in Spanish the concepts that English and other languages have no words for.”

—

Los Angeles Times

“Obejas relates the compelling and disquieting history of Judaism and anti-Semitism in Cuba amidst evocative musings on exile, oppression, inheritance, the unexpected consequences of actions both weak and heroic, and the unruliness of desire and love … Richly imagined and deeply humanitarian, Obejas’s arresting second novel keenly dramatizes the anguish of concealed identities, severed ties, and sorely tested faiths, be they religious, political, or romantic.”

—

Booklist

(starred review)

“An ambitious work … A deft talent whose approach to sex, religion, and ethnicity is keenly provocative.”

—

Miami Herald

“With intelligent, intense writing, Obejas approaches, in ambition, the heady climes of Cuban American stalwarts Oscar Hijuelos and Cristina Garcia. Highly recommended …”

—

Library Journal

“[A] clear-eyed, remarkably fresh meditation on familiar but perennially vital themes.”

—

Publishers Weekly

“[A] soulful, erotically charged, and densely woven meditation on public and private identity …

Days of Awe

is an impressive, almost magical-realistic exploration of Cuban culture, the meaning of exile, and the many roles the closet plays in the history of human identity … Obejas’s deft historical eye for the infinitely subtle gray scale of race, religion, and sexuality is a triumph.”

—

The Advocate

“Obejas writes a rich and sonorous prose and tells her tale obliquely, with shifts and leaps in time and space … She shows that ideas and inspiration are close at hand in a time of cross-cultural ferment, when the world is shrinking and empires are crumbling. There’s plenty of reason to hope for the future of a fiction that welcomes writers with such a passionate sense of the past, both personal and cultural.”

—

San Jose Mercury News

“Achy Obejas has woven together an intricate story of cultural and ethnic intermingling that greatly enriches our understanding of our world and ourselves. Her prose is rich and poetic, and her characters are appealing in their very ambiguity.”

—

Americas

“Achy Obejas in wise fashion tackles touchy issues in the Cuban exile—to be a Jew in the closet, to be gay, always going upstream but always yearning for the homeland. She takes on issues of the Cuban community that have been overshadowed by the never-ending political debate around the future of Cuba after Fidel Castro.”

—

Chicago Sun-Times

for

Memory Mambo

“The power and meaning of memory lie at the heart of Obejas’s insightful and excellent second work of fiction. With prose so crisp, the book could pass for a biography … This is an evocative work that illuminates the delicate complexities of self-deception and self-respect, and the importance of love and family.”

—

Publishers Weekly

“Adept at stream-of-consciousness narrative, Obejas fulfills the musical promise of her title, and mambos her way through this seamless, seductive, and, ultimately, disturbing tale about a time of crisis in the life of a young Latina … Raw, powerful, and uncompromising.”

—

Booklist

“Nothing in Obejas’s story is romanticized. Her work is about exposing truth … She writes a graphically poignant story about believable and interesting characters drawn from experiences close to home.

—

Washington Post

“Memory Mambo

insists on the truth, which in the hands of Achy Obejas is dark, witty, and haunting in its complexity. Achy Obejas is a supremely talented story-teller with a gift for dialogue, character development, and insight into the human condition.

Memory Mambo

is a memorable novel from the first page to the last.”

—

Midwest Book Review

“Its complex story folds back on itself constantly, moving fluidly through time, and through the memories and histories of its many characters.”

—

Village Voice

“The melancholy and sense of displacement that is in the background of Obejas’s collection of humorous short stories is at the heart of

Memory Mambo,

her first novel … Her characters are as flawed and as worthy of compassion as we are; whether we identify as Latino/a, gay, and working class, we are all of us

primos

of exile. Recommended.”

—

Library Journal

This is a work of fiction. All names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to real events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the estate of Nicolás Guillén for permission to reprint “Tengo” (1964) on

Tengo

translation by Achy Obejas. The italicized passage at the top of

The

is a quote from “La Isla en Peso” by Virgilio Piñera (1943); translation by Achy Obejas.

Published by Akashic Books

©2009 Achy Obejas

ePub ISBN-13: 978-1-936-07013-8

ISBN-13: 978-1-933354-69-9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2008925940

All rights reserved

First printing

Akashic Books

PO Box 1456

New York, NY 10009

Para Cary, Eliana, Oscar Luis, Barbarita,

y todos mis vecinos en Tejadillo,

y para Miguel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Thanks to Rafael Acosta, Alejandro Aguilar, Violeta Alvárez, Megan Bayles, Patrick Bergman, Florentina Boti, Christina Brown, Kalisha Buckhanon, Cintas Foundation, Jimena Codina, Norberto Codina, Natasha Díaz Argüelles, David Driscoll, Catherine Edelman, Argelia Fernández, Ambrosio Fornet, Sarah Frank, Carlos Garaicoa (for the giants), Gisela González López, Manuel González, Anna Hirsch, Elise Johnson, Meredith Kaffel, Janice Knight, Llilian Llanes, Carolyn Kim, Leona Nevler, Jim O’Shea, Bajo Ojikutu, Patricia Peláez, Esther Pérez, Don Rattner, Patrick Reichard, Lucía Sardiñas, Charlotte Sheedy, Alma Sías, and María de los Ángeles Torres.

At the

Chicago Tribune

, I’m especially grateful to Geoff Brown, Peter Kendall, Nannette Smith, Kaarin Tisue, James Warren, and everybody in research, especially David Turim.

At the Pilchuck School of Glass, I was ably taught in so many ways by so many: Rik Allen, Marielle Brinkman, Lucinda Doran, Barbara Johns, Paul Larned, Jeremy Lepisto, Steve Marino, Dimitri Michaelides, Pike Powers, and Chuck Vannatta.

At DePaul University, I live in awe of my colleagues in Latin American and Latino Studies: Sylvia Escárcega, Camila Fojas, John Tofik Karam, Felix Másud-Piloto, Lourdes Torres, and the two most efficient women who’ve ever run an office, Cristina Ródriguez and María Ochoa.

I’m in debt to my friend, the writer Arturo Arango, longtime Cojímar resident and witness to the exodus of 1994, who shared his memories of the time with me in correspondence and conversation.

The first chapter of this novel appeared, in slightly different form, in the

Indiana Review

, Vol. 25, No. 1, and I thank the editors for their early and fervent belief in the story.

Thanks, too, to Johnny Temple and the good, good folks at Akashic.

Lastly, this book benefited from the patience, love, and power of two very special people: Tania Bruguera and Eva Wilhelm. Mil, mil gracias.

I am tired, I am weary

I could sleep for a thousand years

A thousand dreams that would awake me

Different colors made of tears

—The Velvet Underground, “Venus in Furs”

U

snavy was an old man

. Not in age so much—he had turned fifty-four that year—but he was born old, his childhood brow prematurely molded into an expression of permanent concern, his gait, even as a youngster, as labored as if he’d been instantly injured on the job, both in spirit and in fact. His pale gray eyes sat in his mushroom-brown face, common and faded, even in boyhood, as if they’d never twinkled or delighted with wonder or awe.

All that summer of 1994, Usnavy had manned his post at the bodega—the one where people came with their ration books to have their monthly quotas of rice and beans and cooking oil doled out—and wordlessly shook his head when people pointed to a page for an item they should have received but which he didn’t have to give. His eyes darted over the void on his side of the counter: soap was scarce, coffee rare; no one could remember the last time there was meat. Sometimes all he had was rice or, worse, those detestable peas used to supplement beans or, when ground up, used as a coffee substitute.

Now and then, when the shelves were particularly bare, he would find himself involuntarily thinking about Belgian chocolates, the kind his mother used to crave: in a box, each nugget tucked into a white paper nest. He imagined giving such a box to his wife, Lidia, and watching her and their fourteen-year-old daughter, Nena, laugh as they shared the sweets, their fingers dotted with cacao peaks. Nothing brought him greater joy than their pleasure; nothing affected him quite like his daughter walking beside him, her fingers laced with his.

At the bodega, Usnavy knew he shouldn’t be partial with what was available. He needed to weigh it out and pour it into the bag for whomever got there first—but Usnavy tried to hoard the bulk of it, just in case, for the most needy: the solitary elderly and the young mothers with kids like kittens clawing at their hems, frantic and unaware that their fathers had hurled themselves into the sea on toothpicks, desperately trying to reach other shores for better luck. After a windsurfing instructor from Varadero had illegally managed the waves all the way to the Florida Keys in little more than nine hours, scores of young men were now seen erecting homemade sails on boards all over the coasts, feigning interest in things like barometric pressure and practicing their skills walking on water.

Usnavy stared at those leaving in disbelief. He wanted to tell them that fate was not in a shoreline or a flag, but in a person’s character. Yet to confront the windsurfers and other mariners meant dealing with the fierceness of their desire—and even Usnavy understood that if the blinding light bouncing off the mirrored waves did not obscure their focus, there was nothing that would keep them from seeing what they wanted to see. They were, each and every one, like Christopher Columbus, insistent on a mainland filled with promise, no matter the truth of the island.

After the morning shift, when the sun was hottest and heaviest, Usnavy would shuffle back home to his family’s Old Havana apartment on Tejadillo street, a windowless high-ceilinged room, no bigger than one of those bloated American cars. Concrete on all six sides, Usnavy’s room in the tenement distorted daylight and time but remained relatively cool throughout the worst of days. A picture of a young Comandante hung in a frame, their only decoration but for a poster of the American singer Michael Jackson, which Nena had gotten as a gift from a friend down the street who’d left for the United States a few years before.

Besides the bed, there was a folded cot, where Usnavy slept so Lidia and Nena could be more comfortable, and a tiny table with a Czechmade electric plate he’d received from the Prague-born wife of a Cuban friend when they had hurried back to her country after the communists tumbled. Next to the plate was a small, white, Soviet refrigerator. Usually, Lidia’s old American iron—much coveted, since irons of every lineage had virtually vanished in the last few years—rested on top, cushioned by a threadbare but very clean towel.

There were books all over the room too, on homemade shelves, tucked under Nena and Lidia’s bed in neat rows, and usually in piles next to it as well. Not just Nena’s school books but also books about Africa, poetry books, books with ambiguous endings by Jorge Luis Borges and Chester Himes (beautifully translated into Spanish), and a young Cuban writer named Leonardo Padura, one of Usnavy’s recent favorites, whose work had been published in Spain and Mexico.

On the wall behind the door, there were a pair of hooks on which Usnavy hinged his bike, his only means of transportation and one of the few things over which he and Nena had occasional arguments. About this, Usnavy was intractable, refusing to surrender his one chance at relief and escape. His official excuse for refusing to let her borrow it was that he couldn’t risk the bike being stolen from her. But in his thinking, she didn’t need a bike: Her school was only a few blocks up, by the capitol building. Of course, Nena was a teenager now and naturally restless. She wanted to be out, to go, anywhere. In his heart Usnavy understood it would be better if she had her own bike, but he simply couldn’t afford it. So as much as he hated to think about it, she’d have to continue walking to get around, hitchhiking like everyone else, and taking the bus, which he knew was often hours late, crowded, and a source of other kinds of dangers too.

Sometimes, he knew, the bus didn’t show up at all. Since the scarcity of fuel had forced the government to cut public transportation service down to bare bones, Lidia, a hospital taxi driver for more than twenty years—one of the first women to really excel at the job—had been laid off and now just shuffled around Tejadillo in a faded housedress most of the time, stunned if not bitter, not because she’d lost her job but because younger men with much less experience had been allowed to stay on.

“They have family,” Usnavy had tried to explain to her.

In the first few months of her layoff, the government had given Lidia a good chunk of her old salary in compensation, but after she’d taken a reeducation course in arts and crafts her take-home pay had been dramatically and embarrassingly reduced. Though she was licensed now as an artisan, there was no paper, no ink, no paint, nothing. The two or three practice prints she’d made in class of Che Guevara and views of dawn in the tropics were smears of color, indecipherable, and long since shredded for note taking and other more intimate uses.

Now, whenever Usnavy tried to rationalize things for her, Lidia bit her trembling lip and looked away, refusing to make eye contact with him, leaving him frazzled and frail.

To relieve the gloom, the family’s room—a breadbox, a shoebox—was illuminated by a most extraordinary lamp. Were it not for the sheer size of it, Usnavy could have built a second floor—a barbacoa—like many of his neighbors. Made of multicolored stained glass and shaped like an oversized dome, the lamp was wild. Almost two meters across, the cupola dropped down with a mild green vine-and-leaf motif that flowered into luscious yellow and red blossoms, then became a crimson jungle with huge feline eyes. (In truth, they were peacock feathers, but Usnavy had never seen or dreamt of peacocks, so he imagined them as lions or, at least, cats.) The armature consisted of branches at the top, black and fat to resemble the density of tree bark. They narrowed as they neared the edge, until they were pencil thin and delicate. The borders were shaped with the unevenness of leaves and eyelids, petals and orbs, in a riotous yet precise design.

Because Usnavy lived in the old colonial district, in a tenement carved out of a nineteenth-century mansion with twisted and enigmatic electric wiring that refused to respond to a central command, while the rest of Havana—in fact, the rest of Cuba—suffered long, maddening power outages and blackouts, Usnavy and his family never lacked the glow of his majestic lamp.

The lamp had traveled with Usnavy from his hometown of Caimanera, the closest Cuban town to the American military base at Guantánamo Bay and the reason for his unusual name: Gazing out her window at the gigantic military installation, Usnavy’s mother had spied the powerful U.S. ships, their sides emblazoned with the military trademark, which she then bestowed on her only son. She pronounced it according to Spanish grammar rules—

Uss-nah-veee

—and for a while caused something of a stir, which other young mothers soon imitated so that by the time the Revolution was upon them, there was a whole tribe of sturdy young Usnavys in Oriente. (In the 1980s, during the Soviet boom in Cuba, there was another inexplicable surge of English-inspired names, particularly Milaydy, Yusimí—

You-see-me

—and Norge, after the refrigerator company.) Usnavy—the original one: Usnavy Martín Leyva—was born in 1940, shortly before Pearl Harbor, when the U.S. might have been thrown off balance but instead sailed off to eager battle the way young people—ignorant of their mortality—recklessly throw themselves into love or revolution. Perhaps as a result of all that, Usnavy carried with him a kind of guilt: At one time, it was possible his mother had loved the enemy (in all fairness, they hadn’t been seen or understood, exactly, as the enemy then), had aspired to the enemy’s might, had tried to project onto him their sense of possibility and optimism.

His father—as Usnavy had been told, a Jamaican laborer (a poor schmuck, he had surmised)—had disappeared into the sea, leaving his mother a widow shortly after he was born, free to rearrange the past at will and dream about the future.

Usnavy remembered her in the radiance of that marvelous lamp—a rush of light in a splendid drawing room at a house called

The Brooklyn

, where important men sat for hours and chatted and smoked while swaying on colonial-style rocking chairs. They played cards and talked of vital things in many languages, like drilling for oil in Texas and African safaris. They bragged about their rhino noses, lion pelts, and elephant tusks, prizes taken from the Serengeti, the stolen home of the Maasai. All the while, a young Usnavy hovered about in the margins, dizzy from the cigar smoke and the buzzing voices. He imagined himself not a hunter or a stateless native, but one with the beautiful beasts, feral and unbound. As each tale of adventure unfolded under the glorious lamp, Usnavy would feel his heart racing, as if absorbing the shock of the shot, from the depth of his guts to the tangle and blockage in his throat. He’d cough and gag until it passed, his mother stroking his young, blondish locks in a contained panic. The men just drank their whiskey, passed bills among themselves, and signed papers.

Usnavy had a memory of his mother as a charming presence, young and tender in the glow. When she moved to Havana many years later, he was comforted to see the lamp in her possession. The luminescence kept her youthful somehow, so that Usnavy never had a memory of her as old, as if the crone whose features served as the only model for his own was a neighbor instead of his mother. She hovered in his peripheral vision, as tantalizingly close and out of reach as a promise. Her burial was a favor he executed for someone he was only remotely connected to, an act of charity meant to ameliorate her aloneness and prove that, in Cuba anyway, no one died without the benefit of community. At his mother’s passing, the lamp was Usnavy’s only inheritance, which he accepted like a reward for exemplary revolutionary work.

In the damp and acrid tenement, the lamp was a vibrant African moon in a room that was by nature s pectral. It was delicate and oversized in a place that demanded discretion and toughness—if it swayed, it might shatter against the concrete. But Usnavy insisted on displaying it.

“What good does it do packed away?” he’d asked Lidia (as if storing it somewhere else were an actual option). “Let’s just enjoy it, it’s so lovely.”

Lately, he knew Lidia fretted because their upstairs neighbors—in violation of both the law and logic—had built up from their second floor room, adding another whole tier for themselves on the roof. Using bricks scavenged from the many edifices that had crumbled in recent times, the neighbors had nearly doubled their space, but the weight of the new construction was taking its toll. In Usnavy’s room, the ceiling already had small cracks, and Lidia had spotted a line of water yellowing the plaster, circling the spot where the lamp was attached. She had tried talking to the neighbors but they dismissed her worries. And when she mentioned it to her husband, he just nodded, never quite registering her concern.

“I’ll talk to them, I promise,” he’d tell her, but he seemed to regard his lamp as invulnerable, and the talk with the neighbors kept dropping on his list of things to do until Lidia became resigned to the problem and the peril.

In the meantime, Usnavy’s only preoccupation seemed to be, as always, maintaining the lamp’s cleanliness and shine, polishing it as if it were a piece of treasure dug up from the sea.

Lidia would stare up at him, as if about to ask something: Her lips would part slightly, quiver, then close again.

Usnavy would stand barefoot on the bed where Lidia and Nena slept and reach up and rub each of the little glass panels with a silk cloth guaranteed not to streak or scratch. A couple of the panels had hairline fractures; Usnavy knew they could pop with the slightest push and he was especially gentle around them.

At night, he kept the light on until the last possible second, engaged in a never-ending staring contest with the lamp’s feline eyes. Sometimes, especially when she was younger, his daughter Nena would curl into the curve under his arm and join him, imagining all the possibilities within the lamp’s vast offerings. That, she’d say, aiming a finger at a green slice of light, was the fertile Nile traversing the continent, and that, he’d point out in the opaqueness of a tiny triangle, the whirling sands on the beaches of Madagascar.

But these days Usnavy was on his own. Now Nena would bury her head under the sheet, ignoring Africa—ignoring him—and sigh loudly and repeatedly until Usnavy finally pulled the lamp’s cord and darkness imploded.