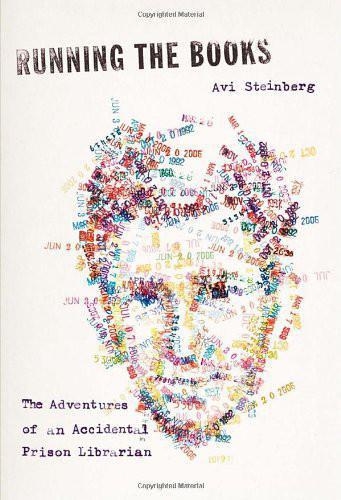

Running the Books: The Adventures of an Accidental Prison Librarian

Read Running the Books: The Adventures of an Accidental Prison Librarian Online

Authors: Avi Steinberg

Tags: #Autobiography

While the incidents in this book did in fact happen, some of the names and personal characteristics of the individuals involved have been changed in order to disguise their identities. Any resulting resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental and unintentional.

Copyright © 2010 by Avi Steinberg

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese / Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Doubleday is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc. Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Alfred Publishing Co., Inc.: Excerpt from “I Get a Kick Out of You” (from

Anything Goes)

, words and music by Cole Porter, copyright © 1934 (renewed) by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Alfred Publishing Co., Inc.

HarperCollins Publishers: “The Diameter of a Bomb” from

Time

, by Yehuda Amichai, copyright © 1979 by Yehuda Amichai; and excerpts from “Cut” and “Edge” from

Ariel: Poems

, by Sylvia Plath, foreword by Robert Lowell, copyright © 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966 by Ted Hughes. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Steinberg, Avi.

Running the books : the adventures of an accidental prison librarian / Avi

Steinberg.—1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Steinberg, Avi. 2. Prison librarians—Massachusetts—Boston—

Biography. I. Title.

Z720.S827A3 2010

027.6’65092—dc22

[B]

2010004829

eISBN: 978-0-385-53373-7

v3.1

To my family

February

19.

Hopes?

February

20.

Unnoticeable life. Noticeable failure

.

February

25.

A letter

.

—FROM KAFKA’S DIARY, 1922

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

PART I: UNDELIVERED

Chapter 1: The up&up and low low

Chapter 2: Books Are Not Mailboxes

PART II: DELIVERED

Chapter 3: Dandelion Polenta

Chapter 4: Delivered

Prologue

Acknowledgments

A Note About the Author

UNDELIVERED

Part I

CHAPTER 1

The up&up and low low

Pimps make the best librarians. Psycho killers, the worst. Ditto con men. Gangsters, gunrunners, bank robbers—adept at crowd control, at collaborating with a small staff, at planning with deliberation and executing with contained fury—all possess the librarian’s basic skill set. Scalpers and loan sharks certainly have a role to play. But even they lack that something, the je ne sais quoi, the elusive

it

. What would a pimp call it? Yes: the love.

If you’re a pimp, you’ve got love for the library. And if you don’t, it’s probably because you haven’t visited one. But chances are you will eventually do a little—or perhaps, a lot—of prison time and you’ll wander into one there. When you do, you’ll encounter the sweetness and the light. You’ll find books you’ve always needed, but never knew existed. Books like that indispensable hustler’s tool, the rhyming dictionary. You’ll discover and embrace, like long-lost relatives, entire new vocabularies. Anthropology and biology, philosophy and psychology, gender studies and musicology, art history and pharmacology, economics and poetry. French. The primordial slime. Lesbian bonobo chimps. Rousseau nibbling on sorbet with his Venetian hooker. The complete annotated record of animal striving.

And it’s not just about books. In the joint, where business is slow, the library is The Spot. It’s where you go to see and be seen. Among the stacks, you’ll meet older colleagues who gather regularly to debate, to try out new material, to declaim, reminisce, network and match wits. You’ll meet old timers working on their memoirs, upstarts writing the next great pimp screenplay.

You’ll meet inmate librarians like Dice, who will tell you he stayed sane during two years in the hole at Walla Walla by memorizing a smuggled anthology of Shakespeare’s plays. He’ll prove it by reciting long passages by heart. Dice wears sunglasses and is an ideologue. He’ll try to persuade you of the “virtues of vice.” He’ll tell you that a prison library “ain’t a place to better yourself, it’s a place to get better at getting worse.” He’ll bully you into reading Shelley’s

Frankenstein

, and he’ll bully you further into believing that it’s “our story”—by which he means the story of pimps, a specialized class of men, a priesthood, who live according to the dictates of Nature.

He means it. Like many a pimp preoccupied by ancient questions, Dice takes the old books seriously. He approves of Emersonian self-reliance, and was scandalized that many American universities had ousted Shakespeare and the Classics from their curricula. He’d read about it in the

Chronicle of Higher Education

.

“You kidding me, man?” he’d said, folding the newspaper like a hassled commuter, brow arching over his shades. “Now I’ve heard it all. This country’s going to hell.”

Men like Dice will inculcate you with an appreciation for tradition, what Matthew Arnold called “the best which has been thought and said.” And you’ll discover precisely why it is so important to study the best that has been thought and said: How else you gonna top it?

T

his at least is what I’m told. I wouldn’t know. I’m not a pimp. I’m in a different sort of racket. My name is Avi Steinberg, but in the joint, they call me Bookie. The nickname was given to me by Jamar “Fat Kat” Richmond. Fat Kat is, or was, a notorious gangster, occasional pimp, and, as it turns out, exceptionally resourceful librarian. At thirty years old and two bullet wounds, Kat is already a veteran inmate. He’s too big—five foot nine, three-hundred-plus pounds—for a proper prison outfit. Instead he is given a nonregulation T-shirt, the only inmate in his unit with a blue T-shirt instead of a tan uniform top. But the heaviness bespeaks solidity, substance, gravitas. The fat guy T-shirt, status. He is my right hand, though it often seems the other way around.

“Talk to Bookie,” he tells inmates who’ve lined up to see him. “He’s the main book man.”

The main book man

. I like that. I can’t help it. For an asthmatic Jewish kid, it’s got a nice ring to it. Hired to run Boston’s prison library—and serve as the resident creative writing teacher—I am living my (quixotic) dream: a book-slinger with a badge and a streetwise attitude, part bookworm, part badass. This identity has helped me tremendously at cocktail parties.

In prison Fat Kat, Dice, and their ilk are the intellectual elite, hence their role as inmate librarians. But the library itself is not elitist. To gain entrance, one need only commit a felony. And the majority of felons, at least where I work, do make their way to the library. Many visit every day. Even though some inmates can barely read, the prison library is packed. And when things get crowded, the atmosphere is more like a speakeasy than a quiet reading room. This place is, after all, the library of “all rogues, vagabonds, persons using any subtle craft, juggling, or unlawful games or plays, common pipers, fiddlers, runaways, stubborn children, drunkards, nightwalkers, pilferers, wanton and lascivious persons, railers and brawlers.” This according to a nineteenth-century state government report. I’ve met only one fiddler. No pipers, common or otherwise. But I do meet a good number of rappers and MCs. With the addition of gun-toting gangbangers and coke dealers, the old catalog remains fairly accurate.

Which is all to say that a library in prison is significantly different than a library in the real world. Yes, there are book clubs, poetry readings, and moments of silent reflection. But there isn’t much shushing. As a prison crossroads, a place where hundreds of inmates come to deal with their pressing issues, where officers and other staff stop by to hang out and mix things up, the pace of a prison library is social and up-tempo. I spend much of my time running.

The chaos begins right away. There is no wake-up call more effective than twenty-five convicts in matching uniforms coming at you first thing in the morning.

First come the greetings. This takes a while. Inmates exchange intricate handshakes and formal titles: OG, young G, boo, bro, baby boy, brutha, dude, cuz, dawg, P, G, daddy, pimpin’, nigga, man, thug thizzle, my boy, my man, homie. Then, the nicknames: Flip, Hood, Lil Haiti, Messiah, Bleach, Bombay, K*Shine, Rib, Swi$$, Tu-Shay, The Truth, Black, Boat, Forty, Fifty (no Sixty), Giz, Izz, Rizz, Fizz, Shizz, Lil Shizz, Frenchy, P-Rico, Country, Dro, Turk, T, Africa …

And, yes, occasionally, Bookie. Incidentally I have other, less-used prison nicknames: Slim, Harvard, Jew-Fro (though my hair is stick straight). Mostly, people just call me Arvin or Harvey.

Next comes business. Every inmate wants a magazine and/or newspaper. Most inmates also want a “street book,” the wildly popular pulp “hip-hop novels” whose titles tend to have the word

hustler

in them. I let Fat Kat handle these requests. Kat keeps a secret stash and runs a snug little business in these books, to which I—for mostly self-interested reasons—turn a blind eye. We have a mutually beneficial arrangement.

Then comes a flurry of random requests. Some legit, some not. Demands to make illicit calls to the courts, to parole boards, to “my mans on the outs,” to mommas and babymommas, wifeys and wifey-wifeys. All denied. Whispered requests for information on AIDS, for information on the significance of blood in urine, for help reading a letter. All noted. I dismiss inmates’ requests to use my Internet for “just one second.” I deflect an inmate’s charges that I’m an Israeli spy; confirm that indeed, I really did go to Harvard, ignore the follow-up question of why I ended up working in prison if I graduated from Harvard. I give serious thought to an inmate’s request for me to check his rap album’s website. I am, after all, the prison’s self-appointed CGO, Chief Google Officer.

I field legal queries. I am asked about the legal distinction between homicide and manslaughter, the terms of probation, sentencing guidelines, the laws relating to kidnapping one’s own children, of extradition, of armed robbery with a grenade. There are also clever criminals: a guy who wants to learn state regulations regarding antique guns and antique ammunition, items he hopes might be governed by laxer laws and fraught with loopholes. Out of the corner of my eye, I notice an inmate sporting a marker-drawn musketeer-style mustache, talking to himself in a phony posh English accent. Somebody might need to take his meds. I note this, as well.