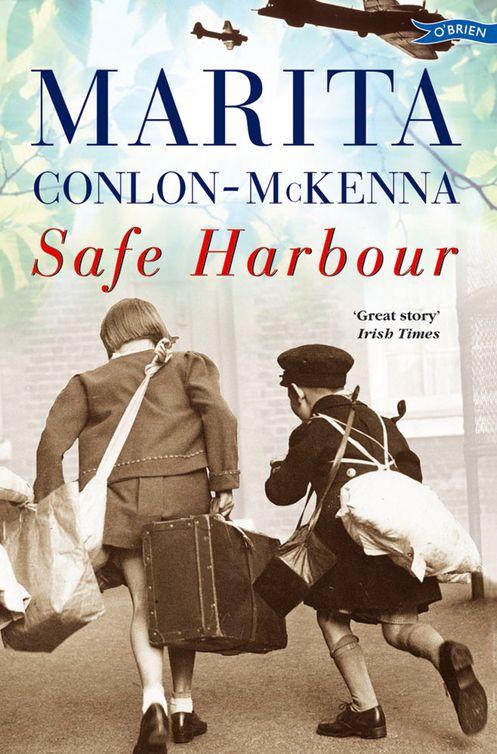

Safe Harbour

Authors: Marita Conlon-Mckenna

Safe Harbour

FROM THE PRIZE-WINNING AUTHOR

of Under the Hawthorn Tree, a book about twelve-year-old Sophie and her seven-year-old brother, Hugh, who are evacuated from the London Blitz. Dad is away at war, Mum is injured and in hospital, and their home is bombed out. London has become a dangerous place, its streets torn apart, its buildings blown up. Each night there is fear of another attack from the skies. The children are sent to Ireland to stay with a grandfather they have never met, leaving behind them all they have ever known.

A moving story of children facing the horrors of war and the heartbreak of a family feud.

Special Merit Award to The O’Brien Press

from

Reading Association of Ireland

‘for exceptional care, skill and professionalism in publishing, resulting in a consistently high standard in all of the children’s books published by The O’Brien Press’

M

ARITA

C

ONLON

-M

C

K

ENNA

For my mother, Mary

Goodnight Children, Everywhere

Goodnight children, everywhere

Your Mummy thinks of you tonight …

Though you are far away

She’s with you night and day.

Goodnight children, everywhere.

Goodnight children, everywhere

Your Daddy thinks of you tonight.

And though you’re far away

You’ll go home one day.

Goodnight children, everywhere.

Song often broadcast on children’s programmes

during World War II

Sophie sang.

Her stomach was rumbling and tumbling with the sounds all around her, the high piercing whistle, and the falling of another bomb, then another. She counted, trying to gauge the distance. She wiped the palms of her hands on her blue cotton dress. She felt sweaty and scared. She could feel a damp line of perspiration on her top lip – just as well it wasn’t too bright in the air-raid shelter.

They were all singing around her to keep their spirits up. Someone down the row from her had started it. Sophie inhaled a large draft of clammy air and tried to concentrate on the song, letting it swell and ripple through her.

A loud thud resonated through the walls of the shelter and the wooden bench Sophie was sitting on moved and shuddered beneath her. The old woman beside her stirred in her sleep and stopped snoring. She had her slippers on and under her cardigan the pink flannel of her nightie peeked through. Obviously she had been prepared for the night.

‘Shove up! Make a bit of room!’ A cross-looking woman was trying to get a space for herself. She had a big bag of knitting with her, and she wedged herself in between Sophie and the woman in the nightie. Sophie wondered how she could possibly see enough to knit in the dim light of the oil lamp, but she just clicked and clacked away, not even

bothering to look at the stitches at all.

‘Hugh!’ Sophie said aloud, suddenly remembering her seven-year-old brother. Her eyes scanned the crowd around her. Finally she spotted him down at the far end of the shelter with an assorted group of kids. Someone had whitewashed the walls of the shelter, and the ‘painting lady’ was there again, with her tins of paint and big chunky bristle brushes, amusing the smaller children. Hugh was semi-crouched, down low, trying to paint what looked like a giant orange butterfly.

‘Think of the colours! Think of the light! Think of the air blowing in the garden!’ said the painting lady cheerfully.

‘Yes, Miss Joyce!’ the little children all chorused.

Sophie smiled to herself. Even in the half-light and from a distance, she could see that some of the butterflies were already being transformed into Hurricane and Messerschmidt fighter planes, looping through the sky. It didn’t matter what the little ones painted – flowers, birds, butterflies – somehow or other they could not escape what was happening above their heads, across the skies of England.

Sophie closed her eyes, trying not to think about it all. Then she heard a loud explosion, followed shortly by another. The whole shelter juddered and everyone went quiet.

‘Go on! Give ‘em hell!’ a man shouted finally, as anti-aircraft guns rat-tat-tatted out in reply to the German Luftwaffe.

Night after night the same thing happened. It seemed as if it was never going to stop. The Germans were determined

to destroy the whole city of London, building by building, bit by bit, night after night.

The knitting woman began a chant:

‘London Bridge is falling down,

Falling down, falling down …’

Sophie joined in, singing it low, to herself, then the old lady beside her moved and began to sing it too, in her half-sleep:

‘London town is falling down,

falling down, falling down,

London town is falling down,

My fair lady.

We’ll build it up with bricks and stone …’

Gradually more voices joined in. As soon as they finished one song, someone would start another.

‘Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall …’

All the old nursery rhymes – ‘Old MacDonald Had a Farm’, ‘Lavender Blue’. Songs of comfort.

The shelter filled with voices. If you sang, you blocked out the noises, the ‘bad’ noises.

‘You’ve a fine voice, dear! Sweet, but strong.’ The old lady, fully awake now, took a triangle of paper from her pocket and held it towards Sophie. ‘Mint humbugs! Good for the throat! Go on, have one!’

Sophie stretched her two fingers in. The sweets were so sticky she had to prise them apart. Eventually she got one and popped it in her mouth.

The old lady nodded, satisfied. Sophie sucked her humbug. Her tongue told her that a bit of paper from the wrapping was still stuck to it, but she didn’t care.

Hugh ran over to her, pushing his hair back off his forehead. He had smears of paint on his hands and a yellow streak across his brow.

He stared at Sophie’s mouth. ‘What you got?’

‘A sweet,’ she replied.

The old lady ignored him. The sweets were back in her pocket and she wasn’t going to offer any more.

‘I’m hungry,’ he whined.

Sophie didn’t like to remind him that it was because of his dawdling at his friend Simon’s house that they had missed tea and were now stuck in this public shelter, just two streets away from home.

‘I want to go home!’ Hugh insisted.

Sophie said nothing.

‘Now! Right now, Soph! I want –’ He stopped suddenly as everyone gasped with one breath. An enormous bang resounded through the shelter. It must be a hit, definitely. They all felt it, really close by. Could it be their street? Sophie wondered in a panic.

‘When it’s over, Hugh,’ she said in a shaky voice, ‘when the All Clear sounds – but it’s not over yet.’

He squatted down on his haunches near her, quiet now. If only he would fall asleep the time would go far quicker, Sophie thought. All the kids were getting scrappy and bored. The painting was finished and now left to dry, abandoned. Miss Joyce was busy repacking the stuff in a box. Then, like

a magician, she produced a bagful of buns and walked around offering one to each child.

Hugh helped himself to a cherry bun.

Miss Joyce stopped in front of Sophie. ‘Go on, take one!’

Sophie nodded her thanks.

Miss Joyce was part of the Women’s Voluntary Service, judging by her uniform. ‘Looks like we’ll be here for the night,’ she said. ‘There’s no sign of this letting up at all.’

Sophie tried to hide her dismay, but Miss Joyce noticed. ‘Are your parents with you?’

‘No,’ Sophie replied. ‘I was on my way home from collecting my brother Hugh when the sirens started so we just made a dash for here. It’s much earlier than usual, and there wasn’t enough time to get home.’

‘Much better to be safe here, though I’m sure your parents will be worried. Do you know where they are?’

‘Dad’s away in the war … and, you see, there’s an Anderson shelter in our back garden,’ Sophie explained, ‘that’s where we usually go. Mum’ll be there.’

‘Well, dear, you’re here now so you’d better make the most of it,’ recommended Miss Joyce, before moving off to talk to a young mother and her new baby.

Sophie yawned and stretched. Back in their own shelter she had a blanket and pillow, and a proper lamp and a pile of her favourite books and some paper and a pen and pencils to do her homework. Here, she was stuck with nothing – and she was responsible for Hugh!

Around her, heads were beginning to nod again. The singing had died away. The knitting needles clicked and

clacked again. The air was getting stuffier and smellier. Sophie managed to turn sideways and squeeze Hugh in beside her. Pulling off her green knitted cardigan, she made a pillow to rest her head against. Hugh kept moaning on and on about the place, but eventually he gave up and slept.

All night the sounds continued, the whinny of one bomb falling after another. Each time Sophie’s heart raced and pounded against her ribs, and she tried not to think of the ground above them falling in and burying them all alive. She could hear the sirens and fire engines and muffled shouts as well as the rumbling drones of attacking aircraft well into the night.

‘Sophie! Wake up!’ Hugh was standing over her, shaking her.

The All Clear sounded.

‘It’s time to go home,’ he announced.

She was stiff and sore. The shoulder of her dress was damp from leaning against the wall. Sophie made an attempt to smoothen her hair, and she shook out her crumpled cardigan and dragged it on. Hugh had bags under his eyes from tiredness, and his mouse-fair hair stood on end. She spat on her fingers to try and flatten it down. The paint stain on his forehead had faded a bit, but he did look a sight.

In future she was always going to carry a comb with her, she decided. Honestly, they looked like two tramps.

Some people were changing their clothes now. Others lay wrapped in blankets still fast asleep, unaware of, or ignoring the early-morning movements around them.

Deftly, Sophie and Hugh made their way to the entrance, picking their steps over the sleepers, and following the crowd upwards and onto the street.

The hazy morning light made them both blink, and the fresh air made them yawn. They gulped in the cold morning air as they got used to being back outside.

‘Crikey!’ Hugh stood rigid, pointing, his eyes almost popping out of his head.

The whole corner of shops across from the shelter was

gone, collapsed into a massive sagging heap of bricks and timber and dust. Smoke sputtered from gas fires that flared from the broken gas mains, which looked like a giant octopus pushing its way up from underneath the pavement. Two or three firemen moved among the debris.

Sophie tried not to think of Mr Brady, the butcher. He had a shop there and lived overhead with his family. She hadn’t seen him in the shelter.

‘Mr Bones – his shop’s gone! Do you think he’s all right, Sophie?’ stammered Hugh.

She nodded, trying to block out the smiling face and kindness of the man in the white apron, who always managed to sneak their mother a bit more meat than the ration book allowed. A few sausages, a nice bit of beef, a small chicken – just because they were part-Irish like himself.

Sophie didn’t want to see the wreckage of his home and business. ‘Come on, Hugh! Mum will be worried sick.’

But Hugh was standing, mouth open with curiosity, pointing to a one-storey section of an office which was almost swaying. ‘Can’t we wait a minute? Maybe the rest of it will fall,’ he pleaded.

‘No! We can’t! Now stop dawdling and come on home!’ She grabbed his sleeve and pulled him after her.

The street behind where they lived was cordoned off. It was a No Go area. Sophie was almost too scared to look as they reached the end of their own street. The street-warden stood there, chatting to a small group of men, and the children managed to slip by them.

‘Mind where you go, you two!’ Mr Thompson, their neighbour, roared after them. ‘You kids shouldn’t be out until we survey the damage here.’

Sophie couldn’t help running as they got nearer to their own house. There was no sign of life. The black-out curtains were still down, and everything seemed very quiet, almost as if the whole of Grove Avenue were still asleep. A shower of dust clung to the front windows, to the redbrick walls and to the blue hall door of number seven, their house.

Sophie had a spare key and let herself into the dark hallway, shouting up the stairs: ‘Mum! We’re home! We had to stay in the shelter on Bury Road!’

There was no reply, and Sophie became aware of that still, strange feeling of an empty house.

Hugh ran down the passageway and pushed open the kitchen door. Plaster and dust rained down on his head, and he put his arms up to protect himself. The kitchen table was set for three, and a plate of buttered bread sat there, curled and hard, mocking them, as bits of upstairs lay scattered around the floor. The scullery door and window no longer existed, and Sophie warned Hugh to be careful of the shards of glass, as every window at the back of the house seemed to have been blown in.

‘Where’s Mum?’ Hugh cried.

‘She’s probably out in the shelter with Mrs Abercorn,’ Sophie tried to convince herself.

They tiptoed carefully through the opening where the back door had been, making their way to the back garden through the yard. The fence between the two small

semi-detached houses had been let collapse over the years, and the man from the Ministry had organised putting a shelter between the two houses, so they could share it.

Their next-door neighbour, Flossie Abercorn, was a widow and a really nice old lady. She had watched the men erecting the shelter and kept saying, ‘Well, I never!’

The man from the Ministry had shown them leaflets with pictures and drawings of how to make good use of the shelter, and how some people grew cabbages and carrots and scallions and all sorts of produce over the roof and sides of theirs.

Flossie Abercorn shook her head. ‘It’s bad enough having to run like rabbits underground because of “Gerry”, but I have no intention of being found dead and buried under a pile of cabbages and cauliflowers and the like. It’s not respectable at my age.’ No one knew her exact age, but it was old.

Mrs Abercorn had planted flower bulbs and seeds and cuttings instead. ‘We’ll have a fine show here in the summer, just you wait and see,’ she told Mum and Dad – her own version of ‘Dig for Victory’.

Sophie made her way to the forget-me-not- and wallflower-covered mound. Hugh chased on ahead. For an instant Sophie looked back. Even their roof sagged.

‘Hugh! Be careful,’ she warned again.

‘Mum! Mrs Abercorn! It’s us, Hugh and Sophie.’ Hugh scrambled down into the Anderson shelter.

‘Oh! Hugh, pet!’ cried their neighbour, hugging the boy, ‘I thought my end had come! One of them bombs must have

landed almost on top of me. Tell me, is the house still standing? Where’s your mother? Where were you all? I was ever so worried. I …’

‘It’s all right, Mrs Abercorn, we … we’re both fine,’ said Sophie.

The old lady looked frightened and haggard. Her hands were shaking and she seemed very unwell. She dabbed at her eyes with a crumpled old hankie. ‘I was so scared all on my own!’

‘Sit down, Mrs Abercorn. You’re all right and we’re here with you now,’ soothed Sophie. She really wanted to shake the old woman and find out where her Mum was, but knew it wouldn’t help matters. She motioned to Hugh.

‘Go get Mr Thompson!’

Her brother disappeared back outside to run for help.

‘You’ll be fine, Mrs Abercorn … a nice cup of tea … plenty of sugar … a warm bed …’

The woman was so cold now that her teeth were chattering. ‘I’ll be fine, love … d … d … don’t you worry!’

Sophie stood watching to see if there was any sign of the warden coming. Her eyes searched the yard and patchy garden. Water sputtered from the broken pipe of the outside tap. A bicycle tyre lay on its own and it took a few seconds before she realised that it was from Hugh’s bike. The rope of the washing line was scattered across the grass where an enormous crater had appeared. Bits of their green hedge blew like tumbleweed … then Sophie became aware of the strange bundle of clothes scattered haphazardly along the path and the stretched doll-like figure in the middle of it all.

‘Mummy!’

She began to run.