Salsa Stories (4 page)

Authors: Lulu Delacre

One

bright clear morning, right before my eighth birthday, Mami took me to my grandma Rosa's, just as she did every morning on her way to work.

“Apúrate, m'ijo,”

said Mami. “Hurry, or I'll miss my ride!”

Leaving a trail of red dust behind us, I ran to keep up with her as she pulled me along the narrow streets of our

barrio

, in the Mexican town of Juárez. Neighbors who trickled out of their houses to start their daily routines greeted us as we passed. But there was no time to stop and talk. Small pearls of sweat rose on Mami's brow and rolled down her carefully made-up face as we rushed along.

Today, as always, Mami had put on a freshly ironed dress, curled her light brown hair, and slipped her old plastic sandals onto her feet. She didn't want to ruin her high heels. So she would put them on just before she reached the Texas border.

When we finally arrived at Mama Rosa's, Mami

quickly bent down and offered me her cheek. “

Dame un beso

, Roberto, give me a kiss,” she said, smoothing back my hair with her hand. “I get paid today. So when I pick you up we'll go to the market to buy the

piñata

I promised you.”

“¡Viva!”

I cheered, hugging her tight. I loved the

piñatas

my friends had on their birthdays, and I had always dreamed of having one of my own. Now, my wish would come true!

Mama Rosa, who had come out to greet us, smiled at my excitement. “And we'll make

chiles rellenos

for your birthday dinner, too,” she added, squeezing my shoulders with her big warm hands.

“SÃ, chico,”

Mami said. “Didn't I tell you that if you got good grades, you would have a special dinner

and

a

piñata

for your birthday? Now, keep up the good work at school, and do what Mama Rosa says.” Then she kissed her mother good-bye and left.

“Be careful at the border!” Mama Rosa called to Mami as she disappeared down the road.

Â

Monday through Friday, Mami worked in Juárez's twin city, El Paso. She would catch a ride in a van with other women who, like her, worked as maids and nannies there. At the American border, she would tell the

guard the same story: She was crossing the border to go shopping. She thought that being all dressed up made her story more believable. As soon as she was in El Paso, she would get on a bus for the long ride to the city's east side. Then she would get off the bus and walk the rest of the way to her final destination. Many other women lived all week in the houses where they worked. They would only return to their families on weekends. My mother was not one of them. She came home every evening to make dinner for us, to mend our clothing, and to check if I had done my homework. And I was glad to have her with me every night.

Â

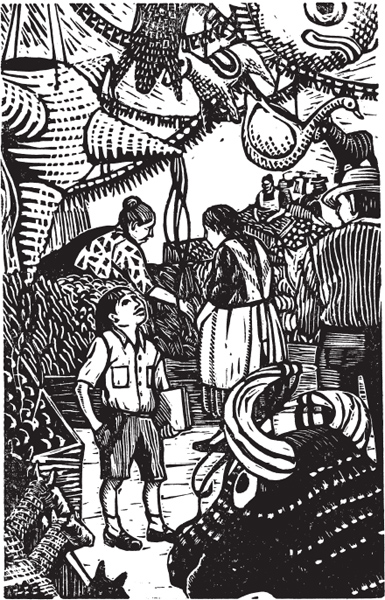

When it was time, Mama Rosa took me to school. And lucky me â to get there, we had to go by the market. In the distance I could see the vendors opening their stands and arranging their wares.

“Can we stop and look at the

piñatas

â PLEASE â Mama Rosa?” I begged.

“How many times have you seen them?” Mama Rosa laughed. But of course, she let me go.

Inside the dark market building we walked past the many stalls filled with fruits and vegetables, purses and handbags, and clothes. And then we came to the one I liked best â the big one that sold

piñatas

. Dozens of

them in all shapes and sizes hung from the ceiling. There were donkeys and horses, cats and dogs, rabbits and fish, and even a silver star. Dazzled by the brilliant colors of the tissue paper that covered them, I stared at each one, hypnotized. Then I looked in the corner to make sure my favorite one was still there â the huge red bull with multicolored ribbons tied to its horns. Standing next to him I could look right into his deep black paper eyes. He was as tall as I was. I was sure he could hold more treats than any other

piñata

there!

“Look!” I whispered to Mama Rosa. “The bull I want is still here.”

“We'll see which one your Mami can buy,” Mama Rosa said with a wink. “But now we must get you to school. Mami doesn't want you to be late.”

“Don't worry,” the vendor joked with me. “The

piñatas

will be waiting for you when you come back.”

Â

In the classroom I told my best friend Pablo about my

piñata

. He was as excited as I was. And all day long, I raised my hand to answer the teacher's questions, hoping to make the day go faster. But it went as slowly as ever.

That afternoon at Mama Rosa's I did my homework right away while I waited for Mami to return from her

job. I kept thinking about my

piñata

and what we could fill it with. In the

barrio

, when someone had a

piñata

, it was hung out on the street, and all the children were invited to share in the fun. I prayed the vendor would not sell my bull before we got there.

When evening came, I sat on Mama Rosa's wooden front steps lost in my daydreams. The shadow of the saguaro cactus on the side of her house grew longer and longer until it faded into the darkness. Where was Mami? I never stayed at my grandma's this long. Would the market still be open after sunset? Behind me I heard Mama Rosa pacing in the kitchen. I was getting very hungry.

Suddenly, Papá appeared.

When he did not find us at home, he got worried and decided to come see if I was still at Mama Rosa's. Inside the house I saw them whisper to each other. Mama Rosa looked anxious as she set the table. The three of us sat down and had some

frijoles

. We ate the beans in silence.

Â

It was late at night when Mami finally arrived. We all rose to greet her as she walked in the door. She looked frazzled.

“You won't believe the day I had!” she exclaimed.

She was out of breath. “This morning they stopped me at the border. They held me for hours, asking all kinds of questions. They asked what was I going to buy ⦠how much I was going to spend ⦠what stores was I going to ⦠I was so nervous, I couldn't even answer. By the time they let me go, it was very late, and I thought I might lose my job. I was lucky Señora Smith didn't get made. Then I worked late to make up for the time I lost.” Mami collapsed next to me on the small couch where I sat, and her head sank into her hands. “I was careful to return after the change of border patrols,” she said.

“I don't like it,” Mama Rosa complained. “What if the guards filed a report? You could end up in jail. Can't you quit?”

“No,” said Mami, weeping. “We need the money I bring home.”

“It is true that with the money you bring we can buy many things we need,” Papá said. “But it is not worth it if you get into trouble. We can do without some things.”

“Like what?” Mami asked. “Roberto's school shoes? Groceries? Mama Rosa's medicine?

I rested my head on Mami's lap. It was almost midnight. She stroked my hair as she talked for a long time

with Papá and Mama Rosa. Slowly their voices became fainter and fainter until they dissolved into my dreams.

Â

The next morning, I woke up in my own bed. Papá must have carried me home. Seated at the foot of the bed Mami was singing

Las Mañanitas

. Still half asleep I realized it was my birthday.

“This evening we'll have your favorite meal,” Mami said when she finished the birthday song. “Mama Rosa is coming to help me make you

chiles rellenos

.”

“

Gracias

, Mami,” I whispered. I was about to ask if I was still getting my

piñata

. But when I remembered how upset Mami had been the night before, I thought it was better not to ask.

“Now get dressed, and after breakfast you'll go with Papá and help him with his errands. I need to clean the house.”

I spent the morning of my birthday with Papá at the hardware store. He was buying materials he needed for a construction job. The store was close to the market, so while Papá payed, I ran to the

piñata

stand. The donkeys and the horses, the cats and the dogs, the rabbits and the fish, and the silver star dazzled more brilliantly than ever. But something was wrong. The corner where my huge bull had once stood was now empty.

My

piñata

was gone!

The burning desert sun was high when we got back home. Inside the kitchen, I found Mami roasting poblano chiles on the flat iron pan. When she finished, Mama Rosa filled them with cheese.

“Roberto,” said Mami. “Go wash up and get me three, big ripe tomatoes from the garden. I need them for the

pico de gallo

.”

Slowly I went out to the garden. While I was excited about my birthday dinner, I knew that without my

piñata

, my birthday wouldn't be the same.

Outside, I found Papá talking with one of our neighbors who was attaching a rope to the roof of his house. Papá leaned over a large bag and slowly removed what was inside. At first I saw a horned head appear. Then I saw a big red body.

“Papá, Papá!” I ran up to him. “It's my

piñata

! The exact one I wanted!”

“I know,” he said. “Mami and Mama Rosa bought it this morning.”

I started to run to get Pablo, but stopped when I heard his shout from behind me. He raced toward us, followed by about twenty other children from the

barrio

. They all lined up single file to hit my birthday

piñata

with a wooden stick. When everyone was there, Papá put a blindfold on the first child in line. All

the other children watched and chanted,

“Dale, dale, dale ⦔

By the time the bull had lost a horn and a leg, it was finally my turn. Papá blindfolded me.

“¡Dale, Roberto!”

my friends cheered. “Hit it!” I aimed high and hit the

piñata

. I heard a muffled thud and took off my blindfold to see only a single orange had fallen.

“My turn!” cried Pablo. He gave two heavy blows, and with the second one, a shower of juicy oranges, hard candy, peanuts, and sugarcane pieces came pouring down from the

piñata

's swaying shards. My

piñata

had more treats in it than any we had ever seen! Amid the laughter and shouting, all the children scrambled on the ground to pick up what they could. When I got up with my hands full, I saw Mami watching me tenderly.

Â

The afternoon wore away, and one by one, my friends left. All except Pablo. Mama Rosa had invited him and his parents to join us for dinner. My uncles, aunt, and Pablo's parents chattered as they ate.

“Feliz cumpleaños, Roberto,”

Mami said as she handed me a plate with two freshly fried

chiles rellenos

, warm flour

tortillas

,

frijoles

, and

pico de gallo

.

“Victoria,” Mama Rosa said. “Are you going back to work on Monday?”

“

SÃ,

Mamá,” Mami answered. “I have to.”

“Don't you think you might get stopped again?” Mama Rosa asked anxiously.

As Pablo and I sank our teeth into the warm chiles oozing with melted cheese, Mami came to me and kissed me on the forehead. “How did you like your birthday?” she asked.

“It was the best birthday I ever had!” I answered.

Mama Rosa and Mami looked at each other, their eyes smiling with silent understanding.

“And that,” Mami said, “is your answer.”

Many

years ago on a misty October afternoon in Lima, Peru, I watched Mamá bake

turrón de Doña Pepa

. Even though she made it every year before the procession for the Lord of Miracles, I had never asked her why.

“Why do you bake

turrón

in October?” I asked. “Why is this the only time they sell it all over the city?”

“¿Por qué, por qué?”

she sighed as she sprinkled the freshly-baked nougat with tiny colorful candies. “Always asking questions, Josefa. Why? It is because this is the month of the Lord of Miracles.”

Not satisfied with her answer, I continued to ask more questions. Who was Doña Pepa? And why do so many people dress in purple around this time? Finally, I wore Mamá out and she said, “I really should tell you the beautiful story that goes with the nougat. After all, you are named after its creator, Josefina Marmanillo.” Then, handing me a piece of the honey-glazed sweet, she led me to the balcony where we sat next to each

other. And as we watched the breathtaking procession down below, this is the story she told.

Â

It all began in colonial times, when Lima was home to the Quechua Indians. It was also home to the Spanish colonists and to the

morenos

, who were brought from Africa as slaves. It was then that an old building with a thatched roof stood inside the city's stone walls. Some say it was a leprosarium. Others say it was a brotherhood of Indians and

morenos

. Yet there are those who believe that it was a barracks for African slaves. What is true, however, is that on a big adobe wall of this building, an Angolan slave had painted an unusually beautiful black image of Christ.

A few years later, in 1655, a powerful earthquake shook Lima. It demolished everything â from government palaces, mansions, and monasteries to the humblest of homes. Thousands of lives were lost to the mighty tremors. But in the wake of its destruction, survivors gathered on top of the rubble of the old building to witness a phenomenal sight. The fragile adobe wall where the

moreno

Christ had been painted stood perfectly intact!

Word of the event spread among the slaves, and the haunting image of the black Christ became a source of

miracles for many. Some of the faithful are said to have been healed of incurable diseases. Others vowed to have been granted long-awaited favors. So in time, the painting became known as

el Señor de los Milagros

. By the 1700s, a church was built to house the image, and the purple-clad nuns from the convent next door became the caretakers of the shrine.

It was around this time that Josefina Marmanillo lived. Josefina was a slave woman who worked on a cotton farm in a coastal valley south of Lima. Known to all as Doña Pepa the

morena

, she spent long days in the farmhouse kitchen kneading, pounding, peeling, and slicing with her big wrinkled hands. And even in the strongest desert heat, she never failed to sing while she worked. She would stop only to laugh when one of the children of the house sneaked in to steal her scrumptious sweets.

One day, while working in the kitchen, a weakness overcame her. Later, she noticed her chores took longer to do. And soon, even the simplest task became impossible. Her cheerful laugh was silenced. And as her arms became paralyzed, her master freed her. For so many years Doña Pepa had thrived on caring for all the people that delighted in her wonderful cooking and baking. Now she was crippled.

That October, when Doña Pepa heard about

el Señor de los Milagros

and the procession that was to be held in His honor, her hopes soared, and she boarded a ship bound for the capital city. The

morena

believed that if she joined the religious caravan and followed the Christ's bier on her knees as a sacrifice to the Lord of Miracles, she might be cured.

It was a chilly day that October when the freed slave arrived in Lima. Above the city hovered the

garúa

, a damp, cold mist that blocked the sun. The city looked as mournful as the procession itself. Doña Pepa looked at the

moreno

Christ from the distance, then fell to her knees and joined the followers. She found herself surrounded by others who, like her, had placed their hopes in the Lord of Miracles. Enveloped by the soothing rhythm of continuous prayer, she accompanied the painting of Christ through long, cobblestone streets and hard dirt roads, until her long skirt was torn and her knees bled. She endured the pain for many long hours, and just as she felt she could not take any more, a tingling sensation suddenly returned to her fingertips. It crept up past her elbows, then went to her shoulders. Had her prayers been answered? Slowly, she clasped her hands together, then she pinched her forearms. She could move her arms and

hands again! She fell to the ground and wept, for the

moreno

Christ had heard her.

“Ay, Señor de los Milagros,”

she whispered. “Whatever you ask of me, I shall do.”

Doña Pepa spent the next few weeks trying to think of a way she could thank the Lord of Miracles. The answer finally came to her in a dream. She dreamed of orange-blossom honey perfumed with lemons and laced with aniseed. When she woke up the next morning, she ran to her tiny kitchen and invented a luscious nougat candy. As soon as it was ready, she filled the tray with the sweet confection and rushed to the courtyard of the

moreno

Christ's shrine where the poor gathered. There, she gave nougat to each man, woman, and child. At first, she told her story to all who asked her why she did this. Then she retold it to all who would listen. It is said that every October until her death, Doña Pepa baked large trays of the golden delicacy to feed to the needy. And as she told her story, she offered them hope for a miracle of their own.

Â

Mamá said as she finished her story, “You know, my dear Josefa, Lima has witnessed hundreds of processions for the Lord of Miracles since they started in 1687. Year after year, you've seen how hundreds of thousands of

believers cloaked in purple, like the first caretakers of the

moreno

Christ, come to profess their faith. And you've seen how in the path of the procession, buildings are lavishly adorned with purple garlands of flowers. You've heard the chants and the prayers that mingle with the fragrance of incense in the dim candlelight. And you've seen the gold-and-silver bier with the painted image of

el Señor de los Milagros

that is carried through Lima's streets. But of all the gifts of song, incense, and myrrh offered to the black Christ, none compare to the humble gift of the

morena

.

“And that is why to this day, Josefa, her delicious nougat is sold on every street corner of the city. It is to remind us what true faith in the Lord of Miracles can bring.”