Salt (7 page)

T

HE EGYPTIANS MADE

salt by evaporating seawater in the Nile Delta. They also may have procured some salt from Mediterranean trade. They clearly obtained salt from African trade, especially from Libya and Ethiopia. But they also had their own desert of dried salt lakes and salt deposits. It is known that they had a number of varieties of salt, including a table salt called “Northern salt” and another called “red salt,” which may have come from a lake near Memphis.

Long before seventeenth- and eighteenth-century chemists began identifying and naming the elements of different salts, ancient alchemists, healers, and cooks were aware that different salts existed, with different tastes and chemical properties that made them suitable for different tasks. The Chinese had invented gunpowder by isolating saltpeter, potassium nitrate. The Egyptians found a salt that, though they could not have expressed it in these terms, is a mixture of sodium bicarbonate and sodium carbonate with a small amount of sodium chloride. They found this salt in nature in a

wadi,

an Arab word for a dry riverbed, some forty miles northwest of Cairo. The spot was called Natrun, and they named the salt

netjry,

or natron, after the wadi. Natron is found in “white” and “red,” though white natron is usually gray and red natron is pink. The ancient Egyptians referred to natron as “the divine salt.”

The culminating ritual of the lengthy Egyptian funeral was known as “the opening of the mouth,” in which a symbolic cutting of the umbilical cord freed the corpse to eat in the afterlife, just as cutting a newborn baby’s cord is the prelude to its taking earthly nourishment. In 1352

B.C.

, the child pharoah Tutankhamen died at the age of eighteen, and his tomb, discovered in 1922, is the most elaborate and well preserved ever found. The tomb was furnished with a bronze knife for the symbolic cutting of the cord, surrounded by four shrines, each containing cups filled with the two vital ingredients for preserving mummies: resin and natron.

Investigators argue about whether sodium chloride was used in mummification. It is difficult to know, since natron contains a small amount of sodium chloride that leaves traces of common salt in all mummies. Sodium chloride appears to have been used instead of natron in some burials of less affluent people.

Herodotus, though writing more than two millennia after the practice began, offered a description in gruesome detail of ancient Egyptian mummification, which, with a few exceptions, such as his confusion of juniper oil for cedar oil, has stood up to the examination and chemical analysis of modern archaeology. The techniques bear remarkable similarity to the Egyptian practice of preserving birds and fish through disembowelment and salting:

The most perfect process is as follows: As much as possible of the brain is removed via the nostrils with an iron hook, and what cannot be reached with the hook is washed out with drugs; next, the flank is opened with a flint knife and the whole contents of the abdomen removed; the cavity is then thoroughly cleaned and washed out, firstly with palm wine and again with an infusion of ground spices. After that, it is filled with pure myrrh, cassia and every other aromatic substance, excepting frankincense, and sewn up again, after which the body is placed in natron, covered entirely over, for seventy days—never longer. When this period is over, the body is washed and then wrapped from head to foot in linen cut into strips and smeared on the underside with gum, which is commonly used by the Egyptians instead of glue. In this condition the body is given back to the family, who have a wooden case made, shaped like a human figure, into which it is put.

He then gave a less expensive method and finally the discount technique:

The third method, used for embalming the bodies of the poor, is simply to wash out the intestines, and keep the body for seventy days in natron.

The parallels between preserving food and preserving mummies were apparently not lost on posterity. In the nineteenth century, when mummies from Saqqara and Thebes were taken from tombs and brought to Cairo, they were taxed as salted fish before being permitted entry to the city.

M

ORE THAN A

gastronomic development, the salting of fowl and especially of fish was an important step in the development of economies. In the ancient world, the Egyptians were leading exporters of raw foods such as wheat and lentils. Although salt was a valuable commodity for trade, it was bulky. By making a product with the salt, a value was added per pound, and unlike fresh food, salt fish, well handled, would not spoil. The Egyptians did not export great quantities of salt, but exported considerable amounts of salted food, especially fish, to the Middle East. Trade in salted food would shape economies for the next four millennia.

About 2800

B.C.

, the Egyptians began trading salt fish for Phoenician cedar, glass, and purple dye made from seashells by a secret Phoenician formula. The Phoenicians had built a trade empire with these products, but, in time, they also traded the products of their partners, such as Egyptian salt fish and North African salt, throughout the Mediterranean.

Originally inhabiting a narrow strip of land on the Lebanese coast north of Mount Carmel, the Phoenicians were a mixture of races, only partly Semitic. They never fused into a homogenous nation. Culturally, other people, first the Egyptians and later the Greeks, dominated their way of life. But economically, they were a leading power operating from major ports such as Tyre.

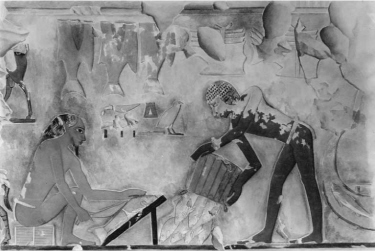

Splitting and salt curing fish is illustrated in an Egyptian wall painting in the tomb of Puy-em-rê, Second Priest of Amun, circa 1450

B.C.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

They traded with everyone they encountered. When Solomon constructed a temple in Jerusalem, the Phoenicians provided both wood—their famous “cedars of Lebanon”—and craftsmen. In the Old Testament it is mentioned that Jerusalem fish markets were supplied from Tyre, and the fish they sold was probably salted fish, since fresh fish would have spoiled before reaching Jerusalem.

It is a Mediterranean habit to credit great food ideas to the Phoenicians. They are said to have spread the olive tree throughout the Mediterranean. The Spanish say the Phoenicians introduced chickpeas, a western Asian bean, to the western Mediterranean, though evidence of wild native chickpeas has been found in the Catalan part of southern France. Some French writers have said the Phoenicians invented bouillabaisse, which is probably not true, and the Sicilians say the Phoenicians were the first to catch bluefin tuna off their western coast, which probably is true. The Phoenicians also established a saltworks on the western side of the island of Sicily, near present-day Trapani, to cure the catch.

Ancient Phoenician coins with images of the tuna have been found near a number of Mediterranean ports. At the time, bluefin tuna, the swift, steel-blue-backed fish that is the largest member of the tuna family, might have attained sizes of over 1,500 pounds each, but this is according to ancient writers who also believed the fish fed on acorns. Seeking warmer water for spawning, bluefin leave the Atlantic Ocean, enter the Strait of Gibraltar, pass by North Africa and western Sicily, cruise past Greece, swim through the Bosporus and into the Black Sea. At all the points of land near the bluefin’s passage in the Mediterranean, the Phoenicians established tuna fisheries.

About 800

B.C.

, when the Phoenicians first settled on the coast of what is today Tunisia, they founded a seaport, Sfax, which still prospers today. Sfax became, and has remained, a source of salt and salted fish for Mediterranean trade. The Phoenicians also founded Cadiz in southern Spain, from where they exported tin. Almost 2,500 years before the Portuguese mariners explored West Africa, the Phoenicians sailed from Cadiz through the Strait of Gibraltar and on to the West African coast.

The Phoenicians are also credited with the first alphabet. Chinese and Egyptian languages used pictographs, drawings depicting objects or concepts. Babylonian, which became the international language in the Middle East, also had a long list of characters, each standing for a word or combination of sounds. But the Phoenicians used a Semitic forerunner of ancient Hebrew, the earliest traces of which were found in the Sinai from 1400

B.C.

, which had only twenty-two characters, each representing a particular sound. It was the simplicity of this alphabet as much as their commercial prowess that opened up trade in the ancient Mediterranean.

I

NLAND FROM THE

port of Sfax are dried desert lake beds where salt can be scraped up in the dry season. This technique, the same as was used 8,000 years ago on Lake Yuncheng in China, and referred to as “dragging and gathering,” was the original Egyptian way of salt gathering, the method used for harvesting natron in the wadi of Natrun. The Arabs called such a saltworks a

sebkha,

and on a modern map of North Africa, from the Egyptian-Libyan border to the Algerian-Moroccan line, from Sabkaht Shunayn to Sebkha de Tindouf, sebkhas are still clearly labeled.

In ancient times, the Fezzan region, today in southern Libya, had contact with Egypt and the Mediterranean. Herodotus wrote of the use of horses and chariots for warfare in Fezzan, which was unusual at the time. Even more unusual, horses also may have been used to transport salt. By the third century

B.C.

, Fezzan was noted for its salt production. Fezzan producers had moved beyond simply scraping the sebkhas. The crust was boiled until fairly pure crystals had been separated, and they were then molded into three-foot-high white tapered cylinders. Traders then carried these oddly phallic objects, carefully wrapped in straw mats, by caravan across the desert. Salt is still made and transported the same way today in parts of the Sahara.

Other books

Water From the Moon by Terese Ramin

The Letters by Suzanne Woods Fisher

Take a Chance on Me by Kate Davies

Deals With Demons by Victoria Davies

Prom Dates from Hell by Rosemary Clement-Moore

Checkered Flag by Chris Fabry

We Are Water by Wally Lamb

River-Horse: A Voyage Across America by William Least Heat-Moon

The sword in the stone by T. H. White

Finding Ashlynn by Zoe Lynne