Sara Paretsky - V.I. Warshawski 10 (26 page)

Read Sara Paretsky - V.I. Warshawski 10 Online

Authors: Total Recall

“I’ll consider it,” she said majestically, “but after

last night’s debacle I don’t trust you to consider the best interests of my

patient.”

I made the rudest face I could muster but kept my

voice light. “I wouldn’t deliberately do anything that might harm Paul Radbuka.

It would be a big help if Mr. Loewenthal could see these documents, since he’s

the person with the most knowledge of the history of his friends’ families.”

When she hung up, with a tepid response to think about it, I let out a loud

raspberry.

Mary Louise looked at me eagerly. “Was that Rhea

Wiell? What’s she like in person?”

I blinked, trying to remember back to Friday. “Warm.

Intense. Very convinced of her own powers. She was human enough to be excited

by Don’s book proposal.”

“Vic!” Mary Louise’s face turned pink. “She is an

outstanding therapist. Don’t go attacking her. If she’s a little aggressive in

believing her own point of view—well, she’s had to stand up to a lot of public

abuse. Besides,” she added shrewdly, “you’re that way yourself. That’s probably

why you two rub each other the wrong way.”

I curled my lip. “At least Paul Radbuka shares your

view. Says she saved his life. Which makes me wonder what kind of shape he was

in before she fixed him: I’ve never been around anyone that frighteningly

wobbly.” I gave her a thumbnail sketch of Radbuka’s behavior at Max’s last

night, but I didn’t feel like adding Lotty and Carl’s part of the story.

Mary Louise frowned over my report but insisted Rhea

would have had a good reason for hypnotizing him. “If he was so depressed that

he couldn’t leave his apartment, this at least is a step forward.”

“Stalking Max Loewenthal and claiming to be his cousin

is a step forward? Toward what? A bed in a locked ward? Sorry,” I added hastily

as Mary Louise huffily turned her back on me. “She clearly has his best

interests close at heart. We were all rather daunted by his showing up

uninvited at Max’s last night, that’s all.”

“All right.” She hunched a shoulder but turned back to

me with a determined smile, changing the subject to ask what I knew about

Fepple’s death.

I told her about finding the body. After wasting time

lecturing me on breaking into the office, she agreed to call her old superior

in the department to find out how the police were treating the case. Her

criticism reminded me that I’d stuffed some of Rick Hoffman’s other old files

into Fepple’s briefcase, which I’d dumped into the trunk and forgotten. Mary

Louise said she supposed she could check up on the beneficiaries, to see

whether they’d been properly paid by the company, as long as she didn’t have to

answer any questions about where she’d gotten their names.

“Mary Louise, you’re not cut out for this work,” I

told her when I’d brought Fepple’s canvas case in from my car. “You’re used to

the cops, where people are so nervous over your power to arrest that they

answer your questions without you needing any finesse.”

“I’d think you could find finesse without lying,” she

grumbled, taking the files from me. “Oh, gross, V I. Did you have to spill your

breakfast on them?”

One of the folders had a smear of jelly on it, which

was now on my hands as well. When I looked deeper into the bag, I saw the

remains of a jelly donut mushed up with the papers and other detritus. It was

gross. I washed my hands, put on latex gloves, and emptied the case onto a

piece of newspaper. Mitch and Peppy were extremely interested, especially in

the donut, so I lifted the newspaper onto a credenza.

Mary Louise’s interest was caught; she put on her own

pair of gloves to help me sort through the rubble. It wasn’t a very

appetizing—or informative—haul. An athletic supporter, so grey and misshapen it

was hard to recognize, jumbled in with company reports and Ping-Pong balls. The

jelly donut. Another open box of crackers. Mouthwash.

“You know, it’s interesting that there’s no diary,

either in here or on his desk,” I said when we’d been through everything.

“Maybe he had so few appointments he didn’t bother

with a diary.”

“Or maybe the guy he was seeing Friday night took the

diary so no one would see Fepple had an appointment with him. He took that when

he grabbed the Sommers file.”

I wondered if wiping the jelly out of the interior of

the case would destroy vital clues, but I couldn’t bring myself to dump the

contents back into the mess.

Mary Louise pretended to be excited when I went to the

bathroom for a sponge. “Gosh, Vic, if you can clean out a briefcase, maybe you

can learn to put papers into file jackets.”

“Let’s see: first you get a bucket of water,

right?—oh, my, what’s this?” The jelly had glued a thin piece of paper to one

side of the case. I had almost pulped it running the sponge over the interior.

Now I took the case over to a desk lamp so I could see what I was doing. I

turned the case inside out and carefully peeled the page off the side.

It was a ledger sheet, with what looked like a list of

names and numbers in a thin, archaic script—which had bloomed like little

flowers in the places it was wet. Jelly mixed with water had made the top left

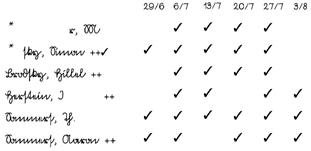

part of the page unreadable, but what we could make out looked like this:

“This is why it’s such a mistake to be a housecleaning

freak,” I said severely. “We’ve lost part of the document.”

“What is it?” Mary Louise leaned over the desk to see

it. “That isn’t Howard Fepple’s handwriting, is it?”

“This script? It’s so beautiful, it’s like engraving—I

don’t see him doing it. Anyway, the paper looks old.” It had gilt edging;

around the lower right, which had escaped damage, the paper had turned brown

with age. The ink itself was fading from black to green.

“I can’t make out the names,” Mary Louise said. “They

are names, don’t you think? Followed by a bunch of numbers. What are the

numbers? They can’t be dates—they’re too weird. But it can’t be money, either.”

“They could be dates, if they were written European

style—that’s how my mother did it—day first, followed by month. If that’s the

case, this is a sequence of six weeks, from June 29 to August 3 in an unknown

year. I wonder if we could read the names if we enlarged them. Let’s lay this

on the copier, where the heat will dry it faster.”

While Mary Louise took care of that, I looked through

every page of the company reports in Fepple’s bag, hoping to find another sheet

from the ledger, but this was the only one.

Stalker in the Park

M

ary Louise

started work on the files I’d pulled out of Rick Hoffman’s drawer. I turned

back to my computer. I’d forgotten the search I’d entered for Sofie or Sophie

Radbuka, but the computer was patiently waiting with two hits: an invitation

from an on-line vendor to buy books about Radbuka, and a bulletin board for

messages at a family-search site.

Fifteen months earlier, someone using the label

Questing

Scorpio

had posted a query:

I am looking for information about Sofie

Radbuka, who lived in the United Kingdom in the 1940’s.

Underneath it was Paul Radbuka’s answer, entered about

two months ago and filling pages of screen.

Dear Questing Scorpio, words can

hardly express the excitement I felt when I discovered your message. It was as

if someone had turned on a light in a blacked-out cellar, telling me that I am

here, I exist. I am not a fool, or a madman, but a person whose name and

identity were kept from him for fifty years. At the end of the Second World

War, I was brought from England to America by a man claiming to be my father,

but in reality he was a committer of the most vile atrocities during the war.

He hid my Jewish identity from me, and from the world, yet made use of it to

smuggle himself past the American immigration authorities.

He went on to describe the recovery of his memory with

Rhea Wiell, going into great detail, including dreams in which he was speaking

Yiddish, fragments of memories of his mother singing a lullaby to him before he

was old enough to walk, details of his foster father’s abuse of him.

I have been wondering why my foster father tracked me

down in England,

he concluded,

but

it must be because of Sofie Radbuka. He might have been her torturer in the

concentration camps. She is one of my relatives, perhaps even my mother, or a

missing sister. Are you her child? We might be brother and sister. I am

yearning for the family I have never known. Please, I implore you, write back

to me, to PaulRadbuka@ survivor.com. Tell me about Sofie. If she is my mother

or my aunt, or possibly even a sister I never knew existed, I must know.

No follow-up was posted, which wasn’t too surprising:

his hysteria came through so clearly in the document that I would have shied

away from him myself. I did a search to see if Questing Scorpio had an e-mail

address but came up short.

I went back to the chat room and carefully constructed

a message:

Dear Questing Scorpio, if you have information or questions about

the Radbuka family that you would be willing to discuss with a neutral party,

you could send them to the law offices of Carter, Halsey, and Weinberg.

These were the offices of my own lawyer, Freeman Carter. I included both the

street address and the URL for their Web site, then sent an e-mail to Freeman,

letting him know what I’d done.

I looked at the screen for a bit, as if it might

magically reveal some other information, but eventually I remembered that no

one was paying me to find out anything about Sofie Radbuka and settled down to

some of the on-line searches that make up the better part of my business these

days. The Web has transformed investigative work, making it for the most part

both easier and duller.

At noon, when Mary Louise left for class, she said all

six policies I’d brought with me from Midway were in order: for the four where

the purchaser was dead, the beneficiaries had duly received their benefits. For

the two still living, no one had submitted a claim. Three of the policies had

been on Ajax paper. Two other companies had issued the other three. So if the

Sommers claim had been fraudulently submitted by the agency, it wasn’t a

regular occurrence.

Exhaustion made it hard for me to think—about that, or

anything else. When Mary Louise had left, waves of fatigue swept over me. I

moved on leaden legs to the cot in my supply room, where I fell into a feverish

sleep. It was almost three when the phone pulled me awake again. I stumbled out

to my desk and mumbled something unintelligible.

A woman asked for me, then told me to hold for Mr.

Rossy. Mr. Rossy? Oh, yes, the head of Edelweiss’s U.S. operations. I rubbed my

forehead, trying to make blood flow into my brain, then, since I was still on

hold, went to the little refrigerator in the hall, which I share with Tessa,

for a bottle of water. Rossy was calling my name sharply when I picked up the

phone again.

“Buon giorno,”

I said, with a semblance of brightness. “

Come sta? Che cosa posso fare per

Lei?

”

He exclaimed over my Italian. “Ralph told me you were

fluent; you speak it beautifully—almost without an accent. Actually, that’s why

I called.”

“To speak Italian to me?” I was incredulous.

“My wife—she gets homesick. When I told her I’d met an

Italian speaker who shared her love of opera, she wondered if you’d do us the

honor of coming to dinner. She was especially fascinated, as I was sure she

would be, by the idea of your office among the

indovine

—p-suchics,” he

added in English, correcting himself immediately to “sychics.” “Do I have this

correct now?”

“Perfect,” I said absently. I looked at the Isabel

Bishop painting on the wall by my desk, but the angular face staring at a

sewing machine told me nothing. “It would be a pleasure to meet Mrs. Rossy,” I

finally said.

“Is it possible that you could join us tomorrow

evening?”

I thought of Morrell, leaving for Rome on a ten A. M.

flight, and the hollow I would feel when I saw him off. “As it happens, I’m

free.” I copied the address—an apartment building near Lotty’s on Lake Shore

Drive—into my Palm Pilot. We hung up on mutual protestations of goodwill, but I

frowned at the painted seamstress a long moment, wondering what Rossy really

wanted.

The page I’d found in Fepple’s briefcase was dry now.

I set the machine to enlarge the copy and came up with letters big enough to

read. The original I tucked into a plastic sleeve.