Saving Henry (22 page)

Authors: Laurie Strongin

Destination: kindergarten.

As Allen and I watched Henry reunite with Ari and Jake and his other friends from his preschool one year earlier, we snapped some photos and fought back the tears. He had a catheter hanging out of his shirt, was swollen from steroids, and his brain-surgery scar was still visible, but he had made it. Enthralled with all the stuff that makes kindergarten a fantasy world, Henry barely even said good-bye.

⢠Making funny faces at Joe

⢠Saying “cheese” or

“queso”

right before a photograph

⢠Getting a hole-in-one in mini-golf

⢠The color gold, particularly when it is sparkly

⢠Chasing (and popping) bubbles

⢠Finding lucky pennies

⢠Slurpees, preferably a cherry/cola mix

H

enry was sure about a lot of things. He was absolutely positive that Batman was the best superhero ever, and that Cal Ripken was the greatest living baseball player. He was certain that eating ice cream first wouldn't ruin his dinner, and that what he had with his girlfriend Bella was true love. He was confident that his Tae Kwon Do training would restore his strength and agility. He knew that root-beer-flavored anesthesia, Batman Band-Aids, and the

sword that his Papa Sy gave him made all the needle sticks and surgeries hurt a little less.

One thing he wasn't so sure about was the tooth fairy.

“How can she fly all over the world and collect all the teeth?” he asked suspiciously.

“How do you know there is only one?” I replied. “Maybe there are lots and lots of tooth fairies,” I posited.

“Good point,” he said.

During his first few months in kindergarten, Henry's friends started to lose their teeth. But not Henry. Henry's teacher took advantage of the growing number of missing teeth to reinforce her lesson in the use of tally marks. Every week an increasing number of gap-toothed smiles produced more tally marks, but not one of them was for Henry. His teeth wouldn't budge. He tried wiggling them. He tried wishing them loose.

“Try now,” he said, asking me to feel how loose his tooth was.

“It's a little looser than yesterday,” I replied. “Definitely.” But in truth, there was nothing doing.

To make sure he was prepared for the big day whenever it came, I bought Henry a small, light blue, silk tooth fairy pillow. It smelled of lavender. The pillow had a little pocket sewn on with small white sequins, and featured the black outline of a tooth. When Henry's first tooth fell out, he planned to put it in the pocket and then put the small pillow under his big pillow in the hopes that the tooth fairy would pay up just like she did for all his friends.

“Come on, you can tell me. Is she real?” he asked at the dinner table one evening, still a little unconvinced.

“She visited me when I was a kid, how about you, Allen?” I replied.

“You bet,” he said.

“How much did she give you?” Henry asked. Clearly the kids at school were talking.

“I hear the going rate is five dollars for the first tooth,” I said.

“Wow,” he responded.

Henry's smile in his kindergarten graduation photo showed a mouth full of baby teeth.

By that summer, Henry's doctors had determined that they needed to extract five of his teeth. The radiation and chemotherapy he had undergone to prepare for the transplant had predictably begun to cause tooth decay. Henry's still-compromised immune system was too weak to fight infection, making it critical to remove the teeth immediately.

“Will it still count?” Henry asked on the way to have surgery at Georgetown where, in addition to removing five teeth, doctors would also insert a tube to stem his ongoing weight loss, yet another harrowing and enduring transplant complication.

“Of course,” I said.

“How will she know where to find me?” He sounded pretty worried.

“Trust me,” I said. “She will. She's magic.”

An hour or so later, Henry's doctors found Allen and me in the hospital waiting room. The surgeries were successful they told us, before presenting us with Henry's teeth.

“We got the teeth, big man,” said Allen as Henry awoke from his anesthesia. We all went upstairs to settle into Henry's fifth-floor hospital room for yet another multiday stay. As night approached, Henry stuffed the teeth into the pocket of his tooth fairy pillow, which he carefully tucked under his hospital-issued pillow. Eventually he fell asleep.

As they did whenever he was in the hospital nearby, Henry's grandparents came to visit. Pop Pop Teddy was first. Figuring that Henry deserved some extra cash, given the anesthesia and all, he rolled up $10 per toothâor $50âand tucked it into the pocket. Nana and Papa Sy offered up a matching gift and tucked in another

$50. When Henry woke up that morning, he reached under his pillow, grabbed the $100, and exclaimed, “She found me!”

The next day Henry shared his news with Jack. “Jackie, the tooth fairy gave me a hundred dollars!” Jack started wiggling his teeth that afternoon, hoping the tooth fairy would find him soon. With a going rate of $20 per tooth, he figured it was a better way to make money than a lemonade stand.

Within days, Henry was discharged from the hospital. Before heading home, Henry insisted that we go to Best Buy, where he procured two new Nintendo Game Boy Advance players, one for him and one for Jack, compliments of his tooth fairy bonanza.

Back home, he couldn't wait to get back to school. By late fall of 2001, it was his favorite place. He was so excited when it was his turn to be Door Holder, one of the special jobs his teacher doled out. He thought being Milk Helper was pretty great too. And when the time finally came to have his central line removed, he brought it to school in a plastic bag to share at Circle Time.

“This is my line,” he explained to his gaped-mouth classmates. “I finally got it out.” Then he passed it around the circle. The kids were a bit baffled by the piece of white plastic tubing Henry dangled in front of them. Apparently they hadn't noticed it hanging out from under his T-shirt for the past year. Later, when I asked his teacher, Mrs. Singer, how the children had responded, she explained that the kidsâand everyone else at the school for that matterâdidn't look at Henry as being sick, just as a really nice friend, and a really determined student. When Henry would get tired, he would go to the school office and lie down with a blanket and pillow in the spot his teacher had created for him to take a nap. When he was done, he would get up, smile, and say to the school receptionist, “Gotta go to class. See you later!”

And then off he would run.

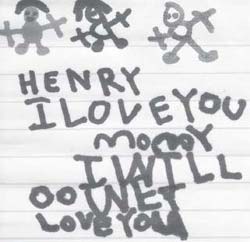

The only job he was never assigned in school was that of the Get

Well Card Helper. This special job was reserved for the times when Henry had to be absent for days and weeks at a time. One student would be asked to collect all the handwritten cards and pictures drawn by the others, put them in an envelope, and get them ready to send to Henry. This job was a quality-of-life saver for Henry, and was, unfortunately, needed a lot more than any of us would have liked.

⢠Climbing trees

⢠His bright blue Pokémon bicycle

⢠Mastering his white-belt basics

⢠Patagonia long underwear

⢠Lightsabers

⢠Wearing flip-flops

⢠Joe

M

osquitoes love Jack.

Therefore, it didn't worry me too much when Jack started to scratch his belly and the first couple of bites popped up. “I'm itchy” just didn't rank high on the list of concerns in our house, or probably anyone else's for that matter, especially one week after September 11, 2001, when it felt like the whole world was falling apart.

An hour later, Jack was still scratching, so I lifted up his shirt

and noticed that he had about a dozen red bumps on his belly. I gave him some Benadryl and put some calamine lotion on the bites and he rejoined Henry, who was watching Pokémon 2000 for the two-thousandth time. I returned to the kitchen where Allen and I resumed our position in front of our small black-and-white TV, watching the jaws of death make its way carefully through the pit of destruction that was once the World Trade Center. The camera focused on the sad, shocked faces of family members walking through the streets, cradling pictures of missing loved ones whose lives they didn't even have a chance to save. Watching this horror, for a few moments I forgot about my problems.

But then something struck me: it didn't seem right. “Why are the bites only on Jack's stomach?” I asked Allen. Before he could answer, I added, “I don't have any, and I always get more than anyone.” Jack and I were in the backyard blowing bubbles together the night before. Allen said he'd go take a look.

While Allen was in the other room, my mind started to wander. Could it be a rash? But Jack had never had a rash on his body before. We hadn't used any new detergent and he hadn't eaten any new foods.

Could it be a bad thingâ

the

bad thing? Could it be chicken pox?

“No!” I yelled to Allen in the other room, as if we had been having a conversation about the possibility. “No way. There is no way that is chicken pox!”

Jack had gotten vaccinated against chicken pox four years earlier when he turned one, mostly to spare him from getting the virus, but also to protect Henry. When the chicken pox vaccination, Varivax, first became available in 1995, it was an enormous blessing for parents of immune-compromised children like Henry, because a disease like chicken pox can cause bacterial infections, such as pneumonia, which his body was too weak to fight. We vaccinated

Henry and Jack at our first opportunity, and every teacher and friend knew to call us immediately if they heard of a case of chicken pox, so we could watch and pray that it passed over our house.

“I think it's just a bunch of bug bites,” Allen said, walking back into the kitchen. I wasn't so sure. I turned off the television and went straight to my computer. While I searched the Internet to confirm that Jack could not possibly have the chicken pox, Allen called our pediatrician to describe Jack's symptoms: itchy red bumps that resemble bug bites, no oozing, no bleeding, and no fever. Jack was a little uncomfortable and tired, but otherwise was fine. They couldn't make a diagnosis over the phone, so Allen drove Jack to the doctor for an assessment while I called Dr. Gillio to see what we needed to do if Jack had the chicken pox.

As I waited for Dr. Gillio to come to the phone, I continued to Google “chicken pox” and frantically looked for more information: What chicken pox looked like. Whether you could get it after being vaccinated or from someone who had been vaccinated. Whether Henry's bone-marrow transplant could have rendered his vaccinations useless. How chicken pox were transmitted. How they were treated. Whether there was anything we could do at this point other than wait. And if getting them really meant Henry could die.

As I was reading and printing and panicking and waiting to hear from Allen and Jack, Dr. Gillio got on the phone. I described Jack's symptoms. Since Dr. Gillio was more than two hundred miles away in Hackensack, he couldn't make a diagnosis. He did, however, tell me about the availability of a vaccination called VZIG (varicella-zoster immune globulin) that held the promise of protecting Henry from getting the chicken pox if in fact Jack had it. Henry would have to get vaccinated within ninety-six hours of exposure, before any symptoms appeared. After he got the VZIG, we would have to wait ten to twenty-one days to see if it worked. During that time, Henry could take IV acyclovir, an antiviral medication he had

taken for a year post-transplant, which should strengthen his ability to fight the disease. To top it off, in the event a vaccination and yet another IV drug weren't enough, Henry would need to avoid Jack for a week or so, just to be completely safe.

If Jack had the chicken pox, then he had been contagious one or two days before the rash appeared, which included the day before, when they made forts in their bunk bed and played for hours in each other's sheets and blankets. The reality is that we didn't know if Jack had the chicken pox, and wouldn't know for certain before the ninety-six-hour window was shut. On the phone, Allen and I weighed the risk of getting the vaccine if Jack didn't have the chicken pox (yet another shot) versus not getting the vaccines if he did (possible death).

I could barely speak. “After surviving heart surgery, brain surgery, and a bone-marrow transplant, he couldn't possibly die of chicken pox, could he?” I finally managed.

We hung up and I called Dr. Aziza Shad, Henry's doctor at Georgetown's hematology/oncology clinic, to see if they had a supply of VZIG, which they did. I asked them to prepare the dosage and to call Corum, our home health-care delivery service, and ask them to send us a supply of IV acyclovir. I called Allen again, who had just sat down with Jack in the sick-kid waiting room at the pediatrician's office. They hadn't seen Jack's doctor yet, but Allen agreed with me that we'd better get Henry to Georgetown so if the pediatrician had any question at all about the possibility that Jack had the disease, we could get Henry vaccinated right away.

“It looks like you're going to have to get a shot today to make sure you don't get the chicken pox,” I said to Henry, while we played chess.

“Oh, man,” he said. “That's no fun.”

“Well, let's get it done now, so we can get to the toy store before it closes. I think this calls for a special treat, don't you think?”

He was so used to getting stuck with needles by that time that he was generally OK with it, particularly if it would lead to the acquisition of a new toy. We got in the car and drove to Georgetown so we'd be there before the hematology/oncology clinic closed for the day. While we were on our way, Allen called to say that the pediatrician suspected that Jack had a mild form of chicken pox, the kind you get if you fall outside the 70 to 90 percent likelihood that, once vaccinated, you won't get it at all.

“Jack's being sent to a pediatric dermatologist in the same building to get a second opinion,” Allen told me.

Just as I hung up, a horrifying thought crept into my head. I was more than eight months pregnant. Though I had somehow failed to absorb the information at the time, I remembered that when I was searching the Internet an hour earlier for any information about the most serious risks associated with chicken pox, I saw something about pregnant mothers and babies and birth defects and death. I called Allen back and asked him to go back and ask the pediatrician what we needed to do to protect our baby and me.

My mind was flooded with another set of questions: Did I have to avoid Jack and Henry? Did I need to get the same vaccination as Henry? Was it safe to get it so far along in my pregnancy? Did we need to give the baby the vaccination as soon as he was born? Was I protected since I'd had the chicken pox as a kid? Was the baby protected for the same reason? Was Jack going to be OK? Was Henry going to die? Were things ever going to get easier? Could I take even one more day of this shit?

But Henry was sitting in his car seat right behind me, so I didn't ask any of them. Instead, Henry and I talked about which superhero was coolerâBatman or Batman Beyond. I preferred the old-school style, but Henry made a good case for Batman Beyond.

“Mom, his Batsuit is so cool. He can shoot batarangs and he can fly. Come on!”

Â

F

or the first time in my life, I was afraid of Jack. Henry and I arrived at the clinic at Georgetown's Lombardi Cancer Center just before closing time, where we learned that the VZIG was actually two shots, not one. I called Allen for an update on Jack. Allen was in with the dermatologist, who was fairly sure that Jack had the chicken pox, but could not say definitely without a blood test and skin biopsy, which involved needles and stitchesâthe equivalent of torture to Jack.

Thankfully, the results wouldn't be available in time to help us decide whether to treat Henry, so we could spare Jack. If we had more time, we would have had to balance the pain and discomfort to Jack with the consequences of not doing it at all. The treatment for Jack if he did or did not have the chicken pox was essentially the sameâoatmeal baths, Benadryl, calamine lotion, or none of the above, depending on how bad he felt. So, it wouldn't feel so great subjecting him to a blood test and skin biopsy, which we knew from experience with Henry involved using something that looks like a small apple corer to extract a chunk of skin, leaving a hole that required stitches. No matter how many times Jack had sat and watched Henry get poked and stitched up, he had never warmed to the idea of having to be the patient himself.

“Let's just get it over with,” Henry said. He had quickly decided that it would be best to get both shots at the same time and just get it over with, so we could get to the toy store before it closed. “Two shots, two presents,” he said. “And one for Jack, too,” he added.

So Henry's two nurse friends, Suzanne and Kathy, each armed with a shot, stood next to me and Henry and we all did the count-

down: “Five, four, three, two, one. Go!” On the way out, Suzanne asked Henry if he'd go on another date with her to Cactus Cantina. “How about tomorrow?” he answered.

And so the decision was made. We would have to wait through the twenty-one-day incubation period to see if it worked. In the meantime, Henry had scored a date out of the deal.

Dr. Shad explained that I wasn't at risk since I'd already had the chicken pox, and neither was the baby as long as he remained in my body. Allen got similar information from the pediatrician and Jack's new dermatologist. I wasn't due for a few weeks, so we still had time to get more information about the risk to the baby once he was born.

As promised, Henry and I headed to Tree Top Toys, a local toy store, to get two treats each for Henry and Jack. Henry picked the card game Skip Bo and a spin-art kit. He thought Jack would like a new several-hundred-piece Knight's Kingdom LEGO set. Henry and I returned to an empty house. I packed a bag for Allen and Jack, and left it along with the LEGOs and a love note on the front porch. Allen and Jack picked up the goods and relocated to my parents' apartment. They planned to stay there for the next five days while Jack was contagious and, thus, the most significant threat to Henry's life. At some point during the waiting period, I would have a baby, and we and our family and friends would find a way to make it through the chaos that continued to define our life.

After Henry fell asleep, I sat alone in the dark in our kitchen and turned on the television, only to learn that in addition to the horrifying terrorist acts that had occurred in New York and Washington and those that may yet occur, potentially lethal letters containing anthrax spores were circulating throughout the country with the potential to deliver death right through our mail slot. Within days, neighbors throughout Washington were sealing their mailboxes,

preferring to collect their mail in plastic bins outside their homes, which they would go through wearing plastic gloves.

I didn't know what to be scared of anymore.

Â

I

stayed home from my job, took my prenatal vitamins, did spin art, and played hundreds of games of Skip Bo, Uno, and Blink with Henry. Each afternoon I looked through the mail spilling into our foyer, convinced that no one would be that heartless.

Three days later, Allen and I couldn't take the separation any longer. Jack's chicken poxâor bug bites or rash (we never did find out definitively what he had)ânever got any worse than they were the first day we noticed them. In fact, they were smaller. The itching was gone and the blisters never came. So Allen and Jack moved into our basement, where they ate their meals, watched movies, slept in sleeping bags, and tried to make a good time of it for another few days. Henry and I lived upstairs, and we all spent a lot of time shouting up and down the basement stairs. After the kids fell asleep, Allen and I met in the kitchen in front of the television. We watched the firefighters search for bodies, bereaved family and friends walk the streets of New York with fliers featuring pictures of lost loved ones, and reports of yet another anthrax-laden letter. We held hands across the table, but we didn't speak. We were too worn out and overwhelmed to say much of anything.

I awoke to an e-mail from Sharon in Israel. She was writing to share with us, Mark Hughes, Arleen Auerbach, and Zev Rosenwaks the most wonderful news: Their third PGD attempt had worked. She was pregnant.

Three long years of struggle, living under the shadow of death have finally reached a dramatic turning point for our family. We

will wake up tomorrow morning with renewed hope. This is a celebration of scientific ingenuity, state of the art medicine, and the most profound expression of human collaboration. Through this long journey yet to be continued, Yavin and I were always guided by a combination of ideas:

A focused attitude of doing everything possible regardless of geographic, financial, physical and emotional difficulties, and a deep understanding of the word “hope” and its role in our life. We always felt that although the outcome of this effort would be crucial, the road we took and the decisions we made along the way would help us get through life in one piece even if we fail. This sober point of view makes us especially happy and relieved today, knowing that thanks to all of your work and effort our future seems to be so much brighter.

Our warmest thoughts are with our very special friendsâLaurie and Allenâwho not only paved the way in a very practical manner, but also reminded us again and again what real optimism and determination are all about. The Nashes, whom we have never met nor spoke to, helped us believe this can really work when we were confronting obstacles along the way.

We send our deepest thanks and appreciation halfway around the globe for all that you have done for our family, and a special thanks in advance on behalf of all those families that will be fortunate enough to be as lucky as we were.