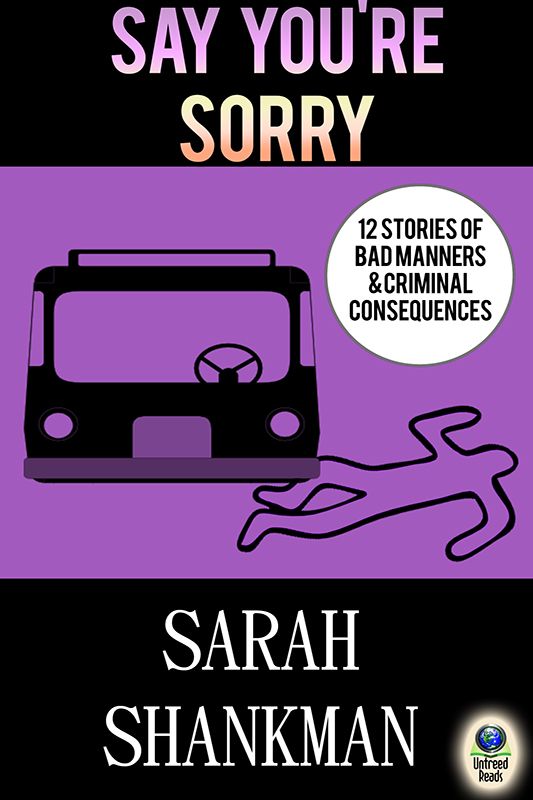

Say You're Sorry

Crossing Elysian Fields on a Hot, Hot Day

Say You’re Sorry: 12 Stories of Bad Manners & Criminal Consequences

By Sarah Shankman

Copyright 2014 by Sarah Shankman

Cover Copyright 2014 by Untreed Reads Publishing

Cover Design by Ginny Glass

The author is hereby established as the sole holder of the copyright. Either the publisher (Untreed Reads) or author may enforce copyrights to the fullest extent.

Stories previously published in print.

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to your ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

This is a work of fiction. The characters, dialogue and events in this book are wholly fictional, and any resemblance to companies and actual persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Also by Sarah Shankman and Untreed Reads Publishing

First Kill All the Lawyers

He Was Her Man

Impersonal Attractions

Keeping Secrets

She Walks in Beauty

Say You’re Sorry

12 Stories of Bad Manners & Criminal Consequences

Sarah Shankman

All You Need Is Love

The whole thing was my mother’s fault.

If she’d said it once, she’d said it a million times:

Georgie Ann, you’re thirty-five years old. If you don’t get out and find someone soon, no one’s going to have you.

I tried not to snap back at her, to remind her that she’d been married plenty enough for the both of us. Most of the time I succeeded. Not always. Everyone has their limits, beyond which they ought not to be pushed.

Look, it’s not as if I didn’t have good reason for being love-shy. Why, I’d been nearly destroyed by the flames of passion. But Mother has a convenient memory, the ability to forget that awful day at St. Philip’s when William detonated my heart. Tiny bits of it stuck to the front of my wedding dress like scarlet polka dots.

Doomsday. That’s what I called it, that gorgeous full-throated spring day five years earlier, when I was left at the altar. You think it never really happens, that old cliché. Well, I’m here to tell you, it does.

I had met William in the most romantic way possible. It was a rainy October afternoon here in Nashville, my thirtieth year, the day after Falstaff, my sweet old pussycat, had passed over to his reward. I’d taken my grief out for a walk, was blindly weeping through neighborhood lanes. I’d missed a curb and had fallen, therefore was both damp and lame.

William came motoring along and spotted me snuffling and shuffling, rather like a character in a country song. He leapt from his car and unfurled his handkerchief, pressing it into my hand. “How can I help?” he asked. “I can’t stand seeing a beautiful woman cry. It breaks my heart.”

Any

beautiful woman?

All

beautiful women? I should have asked. But who thinks beyond the end of one’s nose when the compliments are falling like a fine warm rain?

Besides, William was quite dazzling. Wonderfully charming. Incredibly intelligent. Not to mention sweet. And a good deal more handsome than a man has a right to be. Did I say he was tall? I’m only a hair short of six feet in my stocking feet. You might have mistaken us for brother and sister, with our long limbs, blue eyes, and honey-colored ringlets.

The main thing about William, the architect, was that he made me feel safe. From the moment we met, he felt like home. Not the houses I had skimmed through as a child, barely getting my toys put away before my hummingbird of a mother was packing us up for the next perch, the next husband. William was the home I had always dreamt of. A home whose windows at twilight framed golden Norman Rockwell scenes. A cozy kitchen with soup on the stove. An open book resting on a hassock before an easy chair. A man and woman chatting across a table, the tips of their fingers touching.

I should have noted that William designed mostly high rises. You can see his work in major American cities, sleek and phallic and filled with men in suits massaging cash.

On our aborted wedding day, when William finally called—two hours after the guests had gone, stuffed with crab sandwiches, lubricated with champagne, Mother having seen no reason to waste a perfectly good party—William said that he was sorry, very very sorry, horribly sorry, but, did I remember the Atlanta insurance mogul whose offices he’d been designing? Well, it seems as though the man had suddenly dropped dead, and his really-quite-lovely, much-younger widow was terribly distraught. “You know I can’t stand seeing a beautiful woman cry,” William had said. “It breaks my heart. So I offered her my handkerchief, and then….”

I hadn’t thought that a person could endure such pain. Every cell of my body cried out. My lungs grieved, my skin, my cuticles. Sorrow filled my nights as well as my days, jumped at me from photographs, from letters. A single golden hair of William’s ambushed me from a sweater.

The hands of every clock in my apartment stopped at the hour of my abandonment. If they ever moved after that, I never caught them at it. Each hour was one hundred slow murderous years on the rack. Yet rising from my bed of nails was impossible. Diversion, Mother said. I needed diversion. I needed to get out. But how could I?

I was blind with weeping, but I could still hear the whispers:

Georgie Ann, the poor thing. Deserted. Altar. Pitiful. Would die myself.

I resigned my job by telephone. “Dr. Wilson,” I croaked at the head of the English department, “the worms are at me. I won’t be back again.”

He protested, of course, but to no avail. How could I stand before a classroom of sweaty undergraduates to explain the sexual imagery of

Love’s Labour’s Lost

? Navigate the crannies of the heart with Byron, Shelley, Keats, the Three Musketeers of Romanticism?

I couldn’t. For quite a long time, I could do nothing but contemplate my own demise.

I lay upon my bed and considered my father’s old hunting rifle. I pulled it from the back of my closet, loaded it, racked it back and forth. I became enchanted with that racking. It called to me like a siren. But, my mother’s daughter in that regard, I couldn’t bear the thought of blood and brains and teeth and bone splattered across my snowy ceramic tiles.

I dreamed of Virginia Woolf, and one gray afternoon found myself swaying for hours at the edge of Percy Priest Lake, my pockets filled with stones. But my imagination showed me my pale bloated face, nibbled by perch, and I had too much pride to ever let anyone see me like that. So I trudged back home to pore over the labels of antkiller, rosedust, ammonia, to count the sleeping pills my family doctor had scrawled a prescription for, pressed into my hand on the steps of St. Philip’s on Doomsday. He’d had a crumb of crab sandwich on his lip.

Then, of course, there were the days when my agony would flip-flop and point itself outward, full speed ahead, like a divining rod, toward William. And I would recite a rosary of palliatives: guns, knives, ropes, bombs. But those thoughts passed, and in the end I opted for seclusion, solitude, retreat.

I took a very early retirement from the world.

Rilke said it best: “…your solitude will be a hold and home for you…and there you will find all your ways.”

I withdrew into my home. I lived quite comfortably in a rambling top-floor apartment in one of Nashville’s oldest apartment complexes, a gray elephant of a place shingled in softly silvered wood. I had two huge bedrooms, an L-shaped living room with French doors opening into a high-ceilinged dining room, closets galore. I’d moved in when I’d returned to Nashville right after graduate school and had never had any reason to leave.

Now, I thought, I never would. I had a little money from my father. Invested wisely, it would see me through to the grave. I would never have to leave my apartment again. Not alive, anyway.

Five years passed, and I didn’t set foot across my threshold with the sole exception of annual visits to the dentist and doctor. The pansies and petunias in my windowboxes came and went. I cooked. I read. I cut my own hair. Catalogues, mail order, groceries by phone, books, magazines, newspapers, everything I needed came to me. I didn’t desire the world. I didn’t miss it. I was perfectly content.

Mother, of course, wasn’t. She called me noon and night. “Georgie Ann, this isn’t natural. You must go out. You must have a life.”

“I do, Mother.

My

life.”

She tried every subterfuge known to woman. She said she was dying. I waited, and she didn’t. She proffered a first-class trip around the world. I demurred. The President of the United States was in town. He was coming for dinner. “Really, Mother,” I said.

The next day, there it was in the Nashville

Banner

. The President and First Lady and the President’s most attractive, not to mention single, campaign advisor, had indeed dined with my mother and stepfather Jack, a major fundraiser here in Tennessee.

“I am sorry I missed that,” I allowed. And I was. I would have horsed myself out for the First Couple.

I shouldn’t have admitted it. Mother saw a chink in my defenses, and she went hog wild.

What she did, precisely, was she burned me out.

She would never admit it, of course, but the very next night after the President’s visit,

someone

started a fire on my service porch. It gobbled the whole apartment—filled with over-stuffed furniture, old lace, gauzy curtains—in twenty minutes flat. Thank goodness it didn’t spread to other units. I had time to grab only a few clothes, the sterling flatware handed down from Gram, and Wabash, my cat.

Now where was I to go? To Mother’s, it seemed, as she and Jack showed up so conveniently, Stepdad Number Five wheeling his big old Mercedes through the fire trucks. My neighbors had called, Mother said.

“Bullshit,” I spat. “You torched my home.”

“Oh, Georgie Ann,” she said. “Don’t be ridiculous. Come stay with us in Belle Meade. You can have the whole guest wing. You’ll never even see us.”

Having no other choice, I took her up on it. I’d squat in their red brick mansion on the very best street of Nashville’s very best neighborhood, but only for a bit. Seeing that she had to work fast, Mother was parading prospects past my door before I’d washed the smoke from my hair.

“Mr. James here is just stopping by to talk about our portfolio.”

“Mr. Jones is helping Jack with his will.”

“I don’t believe you’ve met Mr. Smythe. He’s down from New York developing that new shopping center.”

There was nothing palpably wrong with any of these men. No two-headed monsters. No machetes secreted behind their backs. Not even a single pot belly.

But I wasn’t interested. I would never be interested. “Look, Mother,” I said, “all I want is to collect my fire insurance and get myself relocated.”

“And lock yourself up again?”

“I can’t see why not.”

It was then that Mother actually rolled on the floor. It was a scene from a bad novel. She screamed and, furthermore, rent her clothing, a perfectly lovely rose-sprigged afternoon dress.

I was impressed.

“Oh, all right, Mother,” I relented. “I’ll go outside, occasionally, if you will promise never ever to try and fix me up again.”