Scarface (12 page)

Authors: Andre Norton

While Sir Francis was obeying that order Justin wandered around the cove. As far as he could see none but the tide and the birds had ever been there before them. Even the goat path showed no evidence of any feet save their own. And yet there was the knife and it had been recently lost. There was no dimming of the steel by time or weather.

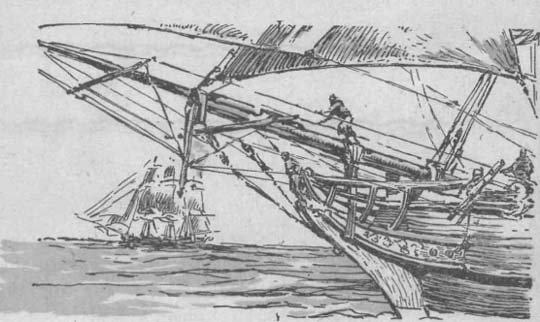

“Justin, here comes a boat! We’ll have company at our fishing.”

With his hand on the knife in his belt Justin turned. Young Hynde was right, a small dugout was heading into the cove, its single passenger dipping his paddle with the ease of one knowing full well where he was bound.

“Why, ’tis only Danby Johns,” Sir Francis said disappointedly.

“Send him away, Justin, else he’ll make our ears ring with his old talk of flowers. The lack-wit!”

Johns had sighted the two on shore. His bristled jaw dropped and he was the picture of dull astonishment. But he pushed on until he was able to splash through the surf and draw up the dugout above water level.

“Whar be th’ other?” he asked.

“What other?” Justin countered. With a quick hand he shut off the stream of questions about to burst from Sir Francis.

“ ’Im wot wos ’ere afore.” Danby screwed up his face in a visible mental activity. “Ain’t I seed ye afore, marster? In th’ night time loike?”

Had Justin been alone he would have claimed drinking acquaintance with the fellow, but because Sir Francis stood there—all ears—he hesitated too long.

“Aye, now I ’members. Ye would ’ave me speak o’ them wot comes at night! Got any rum, marster? I’ll be yer man right willin’ fer that.”

“There’s no rum here,” Justin said brusquely. Sir Francis was looking at him oddly, drawing a little apart so that he could watch both Danby and Justin. “Who is the man you came to meet?”

“Why ’im wot ye wanted to ’ave word wi’ afore, marster. Th’ Cap’n who’ll settle Marster Shrimpton—may th’ Lord rot th’ flesh from ’is stinkin’ bones! Leavin’ a pore owld sailor man wot always did right t’ lie in jail fer want o’ a ’andful o’ shillin’s. Black-’earted ’e is, that’s wot— plain black-’earted!” Danby was now so deep in his own woes that Justin had to shake him to gain attention.

“But this captain is to meet you here?’

“Aye. Wot ’ave ye done wi’ ’im, marster?” Danby stared about him as if expecting to see someone rise out of the sand.

“There’s no one here now—”

“Then I’ll wait. Mayhap ’e’s fergot th’ hour loike.” Danby dropped down into the sand, taking no further interest in the other two. Justin waved Francis back against the rock wall of the cove where he joined him.

“Listen to me now, Francis,” he half whispered. “This may be of grave importance. Sir Robert does not lie at home tonight so we cannot reach him. But do you go to your uncle as speedily as you can and show him that knife you found. Tell him what Johns has said of meeting someone here and that I will stay hid above that I may spy upon this meeting—”

Francis twisted out of his grip with some of his old petulance.

“Why must I go? I want to see too—”

Justin took firm hold of the remaining rags of his patience. “Because that message must surely reach your uncle and there is no one else to go. I am depending upon you for this, Francis. Now we shall leave here together, but when we are above and out of sight, you will go on alone. Come.”

They did just as Justin had planned and Johns watched them scramble out of sight with little interest. Luckily their second contest of wills occurred well beyond the rim of the cliffs. There Sir Francis flatly refused to do as he was bid and Justin used his final weapon—the threat that their fencing lessons were ended for all times.

“Sir Robert will make you teach me!”

“Francis, you are acting like an unbreeched babe!” snapped Justin. “Would you let these pirates escape?”

“Pirates! How know you that it is a pirate Danby has come to meet?”

“I don’t. I only suspect that that is the case. Now get to the Major and he will be heartily proud of you for this —your helping to catch pirates. Mayhap you will even be brought into court to tell your story.”

That last argument told. For Francis set off and left the older boy to find what he hoped would be suitable cover from which he could watch the cove and those in it.

Chapter Twelve

OLD FRIENDS' MEETING

GOOD HIDING places which overlooked the cove were hard to find and the one Justin at length selected was none too comfortable. In fact he thought that he was like to be grilled by the sun unless Johns' friend came quickly. But as yet the old man did nothing but snore in a patch of shade which Justin envied him fiercely.

Lulled by the heat and silence Justin himself must have

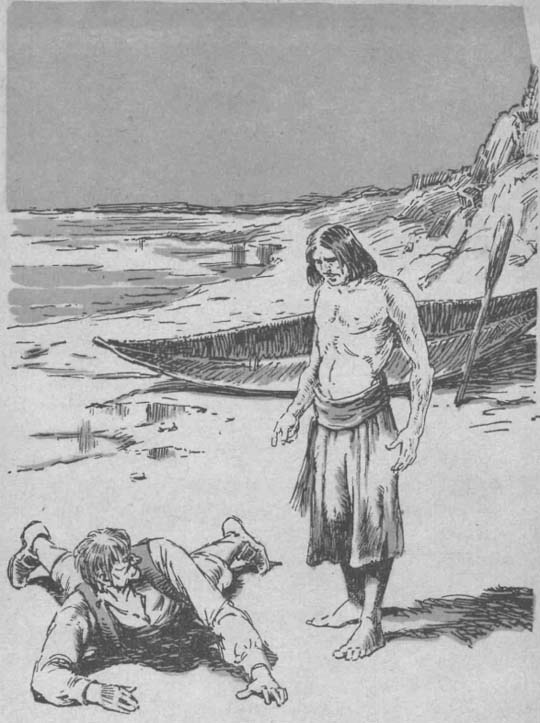

dozed because when the man they both awaited came, it was without his seeing. He roused just in time to see a half-naked half-breed fetch Johns a savage kick.

“Up wi' ye, ye rum bottle!”

Danby grunted and then, opening his eyes, scrambled up in a great hurry.

“Aye, Cap'n. âEre I beâ”

“ âEre ye be a-snorin' so half th' island could come humpin' up without yer seein'! Addle-pate!”

The red-brown hand of the breed slapped full across Johns' face with force enough to send him sprawling back across the rock beneath the shadow of which he had been sleeping.

“No one be'ere,” he jabbered hastily. “They wos gone âours agoâ”

“They? An' who wos they?” The breed came closer to Johns, his hand at his sash. But Johns had noted that gesture and now he fairly babbled.

“Boysâthey wos fishin' loike. But they was goneâ'ours ago.”

“Boys!” The breed turned away from Danby and began a search of the cove, examining the sand and the edge of the cliff track with care. Something he found at the latter place froze him for a long moment and then, as a cat might leap, he was back to catch Johns' bent shoulders in a racking grip which brought a thin whimper from the old man.

“What manner o' boys, ye lack-wit? There be th' mark o' âeeled shoes on that path!”

“They wos quality right enough. One o' âem wos that

brat as lives wi' Major Cocklyn. An' th' otherâloikely âe's gentry tooâ”

“Ye bottle-befogged numskull! Ye fish-brained dog! âEre ye âad th' whole answer t' our riddle in yer 'andsâan' let 'em go! What wouldn't we give t' get Cocklyn's brat! I 'ave a fair mind t' see th' color o' yer liverâ”

By some feat of strength, which Justin would not have believed the frail old man still had in him, Danby broke out of the other's grip and ran towards his dugout, striving to thrust it into the sea. But the breed did not follow himâexcept with a contemptuous burst of laughter. And when Johns discovered that no pursuer was breathing down his neck, he turned and faced inland again.

“Ye never said as 'ow ye wanted 'em,” he whined.

“True enough. An' who can expect wit from a broken pate? No, I'll not lay finger on ye now, Johns. Come back, ye 'ave word fer meâ”

Warily Johns left the refuge of the dugout, but he kept a boulder well between them as he returned.

“Ye be no mad at Johnsâ”

“Mad? No, we're th' best o' friends, Danby. Now then, what news do ye carry?”

“Marster Shrimpton, 'e âas bin t' th' Governor, 'e 'as. But thar ain't no sloop o' war t' spareâthat wos wot th' Governor said t' 'im. An' 'is Cap'nâ'e say'e ain't afeared o' any pirate livin' an' that 'e is willin' t' sail. Sa Marster Shrimptonâ'e be still two ways 'bout it. Only them in townâthey says 'is luck is runnin' out. An' two men from th' brigâthey cut an' run larst night. They 'eard some storiesâ”

The breed chuckled. “Likely they did, likely they did.

“

Up wi' ye, ye rum bottle!”

Well, so Marster Shrimpton is still o' two minds? We must change that, an' speedily, so âe'll o' oneâours! I 'ave a use fer th'

Endeavor

an' th' time is runnin' out. âEre.” From his sash he pulled a purse and tossed it to Johns who snatched with eager fingers. “Go drink an' tell more tales to th' sailors.”

“Aye. Right ye be! An' wot 'bout th' other oneâ”

“Th' other one?”

“Aye, th' lad wot 'as bin arskin' fer yeâ”

The other man was still. Beneath the twisted rag he wore around his head, greasy locks of hair made a ragged fringe to hide his forehead and eyes and a coarse beard masked mouth and chin. But about him there was something oddly familiar, so that Justin longed to see him more clearly.

“Someone 'as bin arskin' fer me, John's?”

“Aye. Came down in th' night an' give me rum 'e did an' arsked 'bout those from th' sea. Thar be 'em in th' town as says 'e is one o' ye wot is a-lookin' out news from the' Governor fer ye. Marster Shrimpton, 'e does say 'e should be in th' jail alongside o' 'em othersâ”

“So that one 'as bin a-arskin'â Well, wonders thar 'ave bin in th' pastâone can never tell. Should 'e arsk again, Johnsâ” He hesitated so long that Danby ventured to prompt him.

“Aye

;

âwot would ye'ave Danby do?”

“Iffen 'e arsks againâsend 'im t' me, Johns. By that way ye know ofâ”

Danby was eager enough to get awayârunning his dugout into the waves with the spryness of a younger man. But the breed made no move out of the cove. Instead he crouched

in the sand and started dribbling the stuff through his dirty fingers in an ever widening circle. AlmostâJustin caught a breathâalmost as if he were searching for something lost.

The boy crawled as close as he dared to the lip of the cliff. He was mad to see the man below at closer quarters âbut not so mad that he lost all caution.

Unfortunately there was no way down into the cove which did not lie in plain view and long before he could get down he would be sighted by his quarry. If he could have only hidden down thereâ!

Grunting impatiently the breed got to his feet. Then, before Justin could move to follow, he set off along the shore at a smart pace, scrambling over the rocks at the far end of the cove and splashing through the tide pools. Justin hurried along the top of the cliff, only to be fronted within a few paces by a hedge of thornbushâand, when he had won around that, the shore as far as he could see was bare of all except the birds. The breed was gone.

Tired, hot, and ill-pleased with himself, Justin started back to Bridgetown. And at last he had time to wonder what had happened to Francis. That the younger boy was sulking somewhere and had not delivered the message was evident, and Justin was planning just what he would say to Sir Francis upon the occasion of their next meeting when a familiar figure in an unaccustomed hurry came puffing down the lane toward him.

He had never before seen Amos' dignity so ruffled, his pace so fast, and when the serving man came up with Justin the haste and heat left him panting so that he could hardly demand in steady speech:

“Where be Sir Francis? Look ye, Lady Hynde would 'ave âimâ”

“I sent him to Major Cocklyn a good time ago.”

Amos merely goggled without understanding. “'Er Ladyship is in a tantrum. Best get 'im 'ome, Marster Blade.”

“I tell youâhe is home! I sent him there with a message to his uncle.”

“Th' Major âas bin a-sittin' wi' some gentlemen all th' afternoon. Sir Francis never came. Marsterâiffen somethin' 'as bin 'appenin' t' Sir Francis 'er Ladyship'll 'ave our 'eads, she will! 'E never came 'ome, 'e didn't!”

“Mayhap he went to the governor's palace. We'll look there.”

Privately Justin thought that Francis Hynde was in hiding somewhere, prepared to pay off his guardians with a great fuss. And when they were deep in the search, being berated for their laxness, he would come forth with some tale to excuse himself. It was just the sort of play which Francis liked best.

“Seen Sir Francis, marster?” replied the sentry at the back lane, the favorite entrance of the Baronet. “Aye, 'e did come up th' lane 'bout an 'our since. Wanted t' know iffen 'is Excellency were back yet, 'e did. When Hi said no, 'e were off aginâmet someone down by that far 'ouse thar an' wint off wi' 'im.”

By the far house! Justin flung a word of thanks to the soldier and hurried down the lane, with Amos at his back. The far house was the corner house where the wider lane met a narrow runnel between dwellings. Blank doors and shuttered windows faced them. There was no one on either street as far as they could see.

“Vas you vishing sometings, my fine sir?”

The voice seemed to lisp out of the air and it was Amos who slapped the shutter open so that the weasel visage behind its crack was clear. Hook nose made a parrot's beak upon a mottled white face. But there was no fear in those small dark eyes nor in the crooked mouth which smiled gap-toothed at them.

“Vas you vishing sometings?” the woman repeated.

“Aye.” Justin assembled some small show of manners. “We are hunting a small boy, ma'am. He was last seen talking to a man at this corner. Did you chance to sight him?”

“A small boy is it? Zare vas such a von. He did have him a new knife vitch he showed to ze man. And ze man said that if he vould come vit him zare might be yet a sword alsoâ”

“The man! What was he likeâthis man?”

“Tall he vosâbigger nor you, young sir. And he had no ears on his head. Red vas his hair yet. And he did tell ze young lord zat he vos a sailorman.”

“Which way did they go when they left here?”

“Down zare, young sir. Toward ze harbor yet.”

Amos showed a grave face. “We'd best go t' th' Major, Marster Blade. Iffen they 'ave 'im in one o' those boozin' dens it'll take th' soljers t' 'ave 'im out agin.”

Justin shook his head. “Soldiers would never get him out. That rats' nest can hide âhalf a hundred who'll never be found. No, we needs must chance it alone, Amos. Or better let me goâI have knowledge of such placesâ”

In his impatience he did not heed that the serving man drew a little away from him, nor did he note the strange

new hardness in the man-servant's tone as he answered:

“Aye, marster, doubtless that be best.”

So they parted, Amos going back toward Cocklyn's home while Justin took the downward road in great strides, seeking the noisome tangle of the lower town.

It was to the Harp and Bottle that he went first, for Danby's hints about the place were a clue. And the first man he saw within, once his eyes were accustomed to the murk, was Johns himself with a full tankard before him and a smile of childish pleasure on his bearded lips. Sitting with him were two strange seamen who were deeply interested in what the old man was telling them.

“Be ye alookin' fer some'un, marster?” The half-breed waiter lounged up to Justin, wiping his hands on his rag apron.

“Aye, a child. He has run away and was seen in these parts. I had some hopes he might be foundâ”

“ 'Ere?” the waiter shrugged. “Well, there be brats aplenty 'ereabouts, marster. Take yer pick. But none in th' Harp. This ben't no place fer 'em. Best 'unt along th' wharves loikeâth' lads play at fishin' an' sich thar.”

But Danby had sighted Justin and now he pushed away from his companions with a sudden indifference which left them puzzled, coming up eagerly to the boy.

“'Ow be ye, marster? Are ye asearchin' fer 'em wot ye spoke onâ?”

“Not now, Danby. I am looking for the boy who was with me in the coveâ”

“Then 'ave ye come t' th' right place. Th' Cap'n was awantin' t' see 'im loikwise. Come âere. 'Tis best not t' keep th' Cap'n awaitin'. 'E be an onpatient manâ”

He seized upon Justin and urged the boy toward the back room of the Harp and Bottle, half pushing him through the rough hide door curtain. They were then in an evil-smelling black pocket filled with kegs among which Danby threaded his way with the ease of much practice.

Then the old seaman put his two hands on the wall itself and pushed sharply to the right. A rough panel moved sidewise far enough to leave space for a body to squeeze through. Danby pawed at Justin's arm pulling him into the room beyond.