Schreiber's Secret

Read Schreiber's Secret Online

Authors: Roger Radford

SCHREIBER’S SECRET

Roger Radford

Parados Books

First published in the United Kingdom in 1995 by Parados Books Revised edition 2013

Copyright © Roger Radford 1995 and 2013

The right of Roger Radford to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious add a resemblance to real persons,

living or dead is purely coincidental.

E-book ISBN 978 0 9518998 3 0

Parados Books 72 Redbridge Lane East,

Ilford, Essex IG4 5EZ, United Kingdom

htttp://radford46.wordpress.com

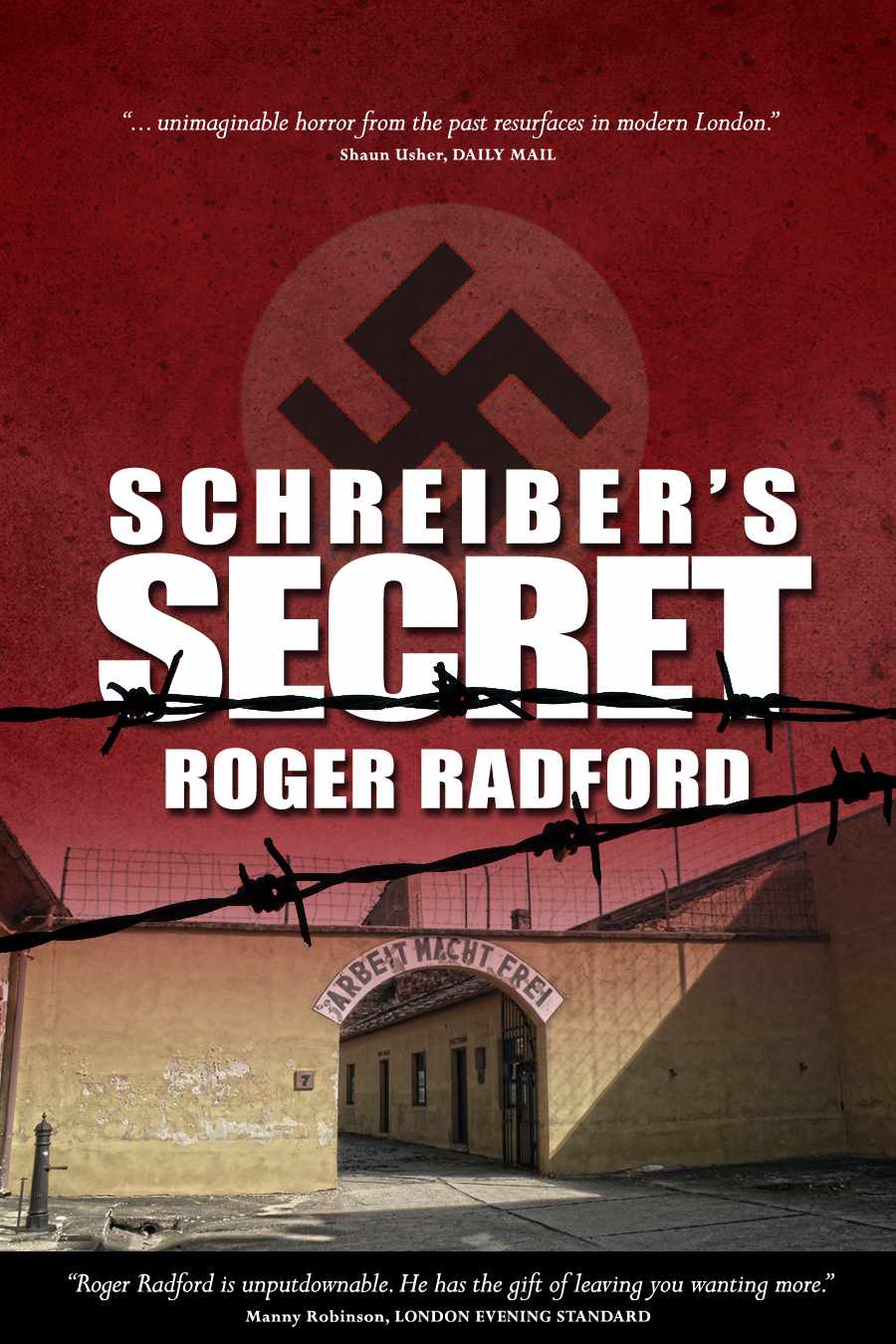

Front cover photograph © Pedro Cambra

Used by permission

Cover Design Concept

by Antony Hepworth of Freshly Squeezed Design

Cover Design Layout and Typography

by Suzanne Fyhrie Parrott

About the Author

Roger Radford is also the author of

The Winds of Kedem

(

international bestseller),

Cry of the Needle

and

High Heels & 18 Wheels: Confessions of a Lady Trucker

(with Bobbie Cecchini). A former war correspondent in the Middle East, he now lives with his wife in London.

‘War criminals deserve the fullest retribution for their crimes...they should be shot on sight without trial...’

WINSTON S. CHURCHILL, 1943.

‘There must be an end to retribution. We must turn our backs upon the horrors of the past, and we must look to the future.’

WINSTON S. CHURCHILL, 1946.

Critics' praise for Roger Radford

...flamboyant action, as unimaginable horror from the past resurfaces in modern London.

SHAUN USHER,

Daily Mail

The hunt for war criminals entered a new dimensional after Britain announced that she would be seeking evidence about citizens living in this country for crimes committed during the war. And Roger Radford, in this, his second novel, has skilfully taken this as the plot for an absorbing book,

Schreiber's Secret

, which follows the initial success of his first novel,

The Winds of Kedem

. The story takes us through the horrors of the Nazi transit camp at Theresienstadt, and how the lives of one of the inmates, Herschel Soferman, and the notorious camp commandant, Hans Schreiber, become inextricably entwined.

Fifty years later, brutal murders in Redbridge stun the world. Two journalists become involved. But all is not as it seems and the journalists, crime reporter Mark Edwards and colleague Danielle

Green, wade deep in red herrings and a twisting and turning plot, including a brilliant description of the Old Bailey court trial of the alleged war criminal. If there was such a word as 'unputdownable' I would use it to describe

Schreiber's Secret

. Radford has the gift of leaving you wanting more.

MANNY ROBINSON,

London Evening Standard and Essex Jewish News

CHAPTER 1

Theresienstadt, winter 1943

“Welcome to Paradise.”

Herschel Soferman, hungry and exhausted after his long and arduous journey from Berlin, dropped his worldly possessions on the dirt-caked floor. The bundle of old clothes stared at him mournfully as his tired eyes lifted towards the source of the greeting. He did not possess the strength even to smile at the outrageousness of it.

“Where are you from?” came the scratchy voice again, penetrating the half-light of dusk struggling to filter through the grimy windows of the barracks.

“I’m a Berliner and I’m hungry.”

“Let me see,” the voice continued, “what day is it today? Friday. You’re unlucky, I’m afraid. Friday is soup. Mondays are best. That’s when we get a small loaf of mouldy bread. The rest of the week it’s soup. If you find a piece of potato in it, you’re a rich man. Otherwise it tastes like dishwater. In fact, we’re all pretty sure it is dishwater.”

The voice took shape and form as its owner stepped forward. “I’m Oskar Springer. I’m from Frankfurt.”

Soferman, unprepared for such verbosity, shook the man’s outstretched hand weakly. It had the consistency of a chicken’s foot. In fact, the Frankfurter appeared to him to resemble a scrawny cockerel. The head, seemingly too large to be supported safely by the emaciated structure upon which it bobbed, was framed by large, fleshy, almost succulent ears. For a fleeting moment Soferman imagined slicing them off and consuming them in cannibalistic fervour. A dry cackle forced its way from his throat.

“I’m Herschel Soferman,” he rasped almost apologetically. “I’m twenty-two. How old are you?”

“I’m twenty-one, Herschel,” Springer sighed, the deep-set eyes belying their age. “I know I look much older,” he added quickly. “Tell me a Jew who doesn’t age nowadays. Especially here. Come, let me show you our room upstairs. It’s paradise compared to the filth here.” The elfin-faced man giggled. “There I go using that word again.”

Soferman smiled weakly. He had been ordered to report to Room 189 of Block 4 of the “Hanover” barracks, and now he was about to find out how luxurious his new accommodation would be. He picked up his rucksack and followed his diminutive host up two flights of stone steps to the first floor and then turned left into a corridor. Springer scampered through the first door on the right. There were twelve bunks arranged closely and in orderly fashion around the room. Upon each

was a mattress and one folded blanket. The residents must all be fellow countrymen, thought the new arrival. The room was so tidy that only a bunch of German Jews could have been responsible.

“You can have the bed next to mine if you like,” said Springer. “We lost Pavel yesterday. TB. It’s a wonder I haven’t caught it yet. Anyway, the one good thing about our barracks being so overcrowded is that we manage to keep warm in winter, although we put on as many clothes as we can.”

The mere mention of the season caused Soferman to shudder. It was freezing. He stepped over to the room’s solitary window and peered out at the courtyard below. Hundreds of people were milling to and fro, cowed not only by the inclement weather. They wer

e

Untermensche

n

, the lowest of the low, and they knew it. Soferman stood mesmerized by them. A procession of pregnant snowflakes began to fall. Everything would be white by the evening.

“I take it you’ve already been to the low barrack to get your identity card stamped,” said Springer, breaking the spell.

Soferman fumbled in the right pocket of his overcoat. He and his travelling companions had been herded from the railway station to the collection centre. There, tired and hungry, they had been searched for forbidden goods and had had their identity cards stamped with the date of arrival and the inscription “ghettoized”.

“You don’t have to show me that, my friend,” said Springer kindly.

Soferman felt foolish as he held up the card. It had been an automatic reaction.

“Come, I’ll show you the washroom. The water’s freezing, but then you don’t exactly smell like a bed of roses.”

As Herschel Soferman followed the smaller man out of the barracks, little did he realize how much he would come to rely on Oskar Springer for his very survival, and how much he would grow to love him for his selflessness and ingenuity.

Furthest from the Berliner’s mind was the notion that he could be forced to act out a drama equal to the most brutal excesses of ancient

Rome.

The two young men learned quickly that they had many interests in common. Both had a passion for the works of Schiller, Goethe and Kant. This was all the more remarkable in Soferman’s case since he had worked in Berlin as a humble presser and was largely self-taught.

Springer had enjoyed the benefit of a university education. They differed also in that the Berliner had spent most of his formative years in an orphanage, while Springer was the second son of a family of eight. The Frankfurter had lost contact with them when the Nazis had decided finally to solve the problem of their own Jews. Every transport was “to the East” and fear of the unknown was not helped by the occasional rumour of mass slaughter, although most people had developed a finely tuned mechanism for denial.

For the first few weeks following his arrival, Herschel Soferman played the willing pupil to Springer’s tutoring. He learnt that Theresienstadt was a transit ghetto set up in the old fortified Czech town of Terezin and that thousands of Jews from Bohemia and Moravia had already passed through on their way to “resettlement” further east. Now it was the turn of Jews from Germany and Austria to flood the ghetto.

“Never volunteer for anything,” Springer told his young ward. “Always keep a low profile and learn to survive by your wits. The longer we stay in the ghetto, the better. And whatever you do, don’t make yourself a candidate for resettlement. The Nazis are word jugglers. They’ve even produced a film. One of the Germans who comes to the cookhouse told me they called it ‘Beautiful Theresienstadt’. It was made by Kurt Gerron. You know, the famous actor and director. Poor bastard. He must have done a wonderful job. They sent him on a transport to Auschwitz and ...”

“Auschwitz?” Soferman cut in.

“Oh, I forgot. You’re fresh meat. You probably haven’t heard of it yet. They say it’s a death camp where they gas and murder Jews. Nobody wants to go there to find out if the rumours are true. Most people think it’s a big ghetto with self-administration like here. I actually once got a postcard from my uncle Mordechai. It was a put-up job, of course. The first few lines extolled the virtues of the place. But then he wrote that he had met Yaacov Weiss, his closest friend.”

“Well, that seems quite positive.”

“Not quite. His friend Weiss was killed years ago. O

n

Kristallnach

t

. But you can’t tell anyone here that everything’s a sham. They just don’t want to believe it.”

Soferman shivered in the chill air.

“Anyway,” Springer went on, “one day not so long ago I saw the director crouching on his knees, pleading with the SS that he had made a magnificent film for them. ‘That’s just the trouble, Jew-swine,’ the SS officer shrieked, ‘it was so good that no one must ever know how you got the shits to act so well.’ He then smashed Gerron over the head with a stick and threw him on the transport.”

With that, Springer danced a sort of macabre jig.

“An actor. Who cares?” he continued as he bobbed up and down. “A painter, a scientist, a candlestick maker. They all end up the same way. Most of them are German Jews like us. You know, those who were more German than German, who’d lost all thei

r

Yiddishkei

t

.” The jig continued.