Read Scribbling the Cat: Travels With an African Soldier Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Military, #General

Scribbling the Cat: Travels With an African Soldier (29 page)

Then I hurried off the rock, across the lawn, and back into the cage before the lion could get any ideas about ambushing me.

I shut the screen door behind me and I stopped, listening. I sensed immediately that K was not asleep. His breathing was uneven and angry. I brushed my teeth and climbed into bed as quickly and quietly as I could. I lay awake for a while, listening to K’s sleeplessness from the other bed, and then I dozed off.

I awoke an hour or two later into the sudden death of a noise, which in this part of Africa is not

silence,

exactly, but more a reduction of something steadying and reassuring and man-made. The generator had been switched off. The startling absence of its companionable throb and the corresponding stillness of the fan’s cooling arms above my bed had jolted me awake. I peeled the sheets off my legs and wiped sweat off my forehead.

Then I heard the crash of something being dropped, a sort of intentionally angry noise that felt

directed

toward me, rather than accidental. Then another noise, this time louder. As if something were being bashed to death. The hesitant pale light of a flashlight caught the kitchen window and blinked at me. I felt my way past the gauzy embrace of my mosquito net and groped toward the kitchen. Mambo paced next to me on the other side of the wire, his scrubby flanks brushing the fence, issuing the breathy grunt that male lions have of expressing themselves: “Uh-uh-uh-uh.”

“Good boy, Mambo,” I told him, not meaning it.

I slipped into the kitchen, where the smell of far-from-fresh crocodile meat was most powerful.

K was hunched over a pile on the floor. His shadow jerked and bulged, gray and enormous on the white wall behind him.

I said, “What are you doing?”

K picked up his bag. It was packed and zipped closed. He wouldn’t look at me.

“It’s the middle of the night,” I said.

“I’m leaving.” K turned around. “You can find your own way home,” he said. He looked murderous, his lips almost purple and his face indistinct.

I leaned against the wall and crossed my arms.

“Get your new friend to drive you home.”

“What’s going on?”

He said, “You know what you’ve done.”

I sighed.

“You’re godless,” K said. Then he added, “And do you know what absolutely terrifies me?” When I didn’t reply, he thrust his head out at me and raised his eyebrows. “Huh?”

“No,” I said.

“I haven’t read my Bible once on this trip,” he said. “Not once.” He breathed at me heavily.

I said nothing.

“I believed in you,” he said. “I trusted you.”

K sent his bag crashing out of the kitchen onto the veranda, where it hit the side of the cage and startled the lion.

K came up to where I was and stood above me. He spoke in such a low, angry voice that it sounded more like he was breathing the words than saying them. “I’ve destroyed all your tapes, your film. You have nothing about this trip. You have nothing to say about me.”

I ducked under his face, sank onto my haunches, and wrapped my arms around my knees. Mambo attacked the cage, trying to paw the duffel bag into life.

“Don’t worry. I don’t hit women,” K said.

I looked up. “I’m not scared.”

“You’re not worth it.”

There was a long silence.

“Evil,” said K, dropping down and pressing his mouth close to my face.

Then he got up and pulled some fishing line out of a reel that had been lying near the kitchen sink and bit through it, so that a small piece of gleaming green line snapped back on his lip. He put the reel into his fishing box and slapped the box shut. “You play with men. You know that? You play with men and you play with their feelings and you are going to destroy yourself. You’re going to destroy your family.”

I stared down at the floor. A line of ants was hurrying from the top of the kitchen table, in long, quivering formation, down the table’s leg and into a crack in the cement at my feet. Each ant carried a grain of white sugar in its jaws. K dropped his fishing box on top of the line and the ants swarmed in a frenzy of confusion. I lifted my feet until the orderly line had re-formed.

When K’s voice came again it was low, but very distinct. “This place is evil. I can feel the evil all around me. It’s like fingers around my neck. That’s how much I can feel evil . . . like fingers around my neck.”

I said, “I don’t know what you’re thinking.”

K laughed humorlessly. “Don’t try that with me.”

“Whatever it is, it’s likely to be worse than the truth.”

“I wasn’t born yesterday.”

“No,” I agreed.

“And you can’t write my story. I won’t let you write about this.”

“It’s not up to you what I do.”

“Yes it is!” Suddenly K imploded, his face fell in on itself, and his shoulders collapsed. “You fucked him, didn’t you? You fucked him!”

I stared at K. I said, “No.” But I knew that whatever I said it wouldn’t make any difference. K had gone into that place in his head that is beyond reason.

“Then if you didn’t fuck him, you . . . you . . . you did something else. I told you,” he hissed, “you have nothing to say about me. I’ve destroyed the interviews. Your film. All of it. You’re evil!”

I glanced up at the shelf, where my suitcase lay and in which I had kept my tape recorder and camera, my tapes, film, notes, and my diary. It was open and my stuff lay strewn across the top of it.

K’s eyes followed mine and he nodded. “All of it,” he repeated.

At that moment I hated K, not for trying to reclaim what he had given me (that I could understand), but for assuming that he could claim what was mine.

We faced each other in the shimmering light of the flashlight.

Then he said, threatening, “I’m leaving.” But he didn’t move.

“It’s okay,” I said. “Leave if you want.” I covered the back of my neck with my hands and rocked back and forth on my heels, curled up completely against K. And against Mapenga and the lion. And against everything these men had ever done and everything they would ever do. And against everything I had ever done and ever would do. I wanted to get off the island and wash their words and their war and their hatred from my head and I wanted to be incurious and content and conventional. I didn’t care about the tapes, or the film. I didn’t care about K’s story or Mapenga’s bravado. I didn’t care about any of it, because putting their story into words and onto film and tapes had changed nothing. Nothing K and Mapenga had told me, or shown me—and nothing I could ever write about them—could undo the pain of their having been on the planet. Neither could I ever undo what I had wrought.

I said, “I’m sorry.”

“What?”

“You’re right,” I said. “I have nothing to say about you.” I stood up and looked at him. “Nothing.”

I had shaken loose the ghosts of K’s past and he had allowed me into the deepest corners of his closet, not because I am a writer and I wanted to tell his story, but because he had believed himself in love with me and because he had believed that in some very specific way I belonged to him. And in return, I had listened to every word that K had spoken and watched the nuance of his every move, not because I was in love with him, but because I had believed that I wanted to write him into dry pages. It had been an idea based on a lie and on a hope neither of us could fulfill. It had been a broken contract from the start.

An age of quiet spun out in front of us. Even the creatures outside had ceased pulsing and calling, as if the heat of K’s anger had rushed out of the room to the world beyond the veranda and stilled the restive frogs, trilling insects, and crying night birds. Sweat gathered in a little stream under my chin and plopped onto the floor between my feet.

He said softly, “You’re not what I thought you were.”

“No.”

Mambo groaned and pressed himself up against the cage, and a rooster from the laborers’ village gave a high, warning howl, “Ro-o-o-o-ooooo!”

K said, “It doesn’t matter.”

“No,” I said. “It doesn’t.”

Because at that moment it seemed to me that who K and I were mattered less than the fact that we were in this together. Two people in a faint pool of light from a dying flashlight beyond which there was darkness, Mambo, an insomniac cockerel, a great stretch of crocodile-rich water, Mozambique, and Africa. And beyond that, a whole, confused world where people like us were doing exactly what we were doing—trying to patch together enough words to make sense of our lives.

Suddenly K’s face was level with mine—he was kneeling in front of me—and I could see, by the light of the lamp, that he was crying. Two silver trails, like the gleaming path left on cement by a snail, shone down his cheeks. “Sorry,” he said. The tears came out of his eyes in sheets and out of his voice in clouds, making his words blurred and sluggish, like a drunk’s. “Shit, I’m so sorry.”

I said, “Me too.”

A mosquito drifted onto my wrist like a casual piece of fairy dust. I pressed it with my thumb and it left a smudge of blood on my skin. I wondered, vaguely curious, if it was K’s blood, or mine.

“Why do I destroy?” he asked.

I said, “Why do I push people to destruction?”

“Because you’re a woman,” he said.

I said, “Because it’s what you do. It’s what you’ve always done. You have a genius for it.”

I waited for his reaction. To my surprise, K took the edge of his shirt and wiped the sweat off my face and the tears from his cheeks. Then he smiled and cupped the back of my head—which, speaking from experience, is not unlike getting cuffed by a lion. He said, “Okay, my girl. Get yourself under a mosquito net before you get bitten to death.”

WE SLEPT FOR a couple more hours. Before dawn I heard K get up. The screen door on the veranda whined open and slammed shut as he let himself out of the cage. I lay in bed watching the gray dawn turn pink and the lake magic itself into a shiny, flat, rose-colored mirror. Mapenga was up—I heard him talking to the lion as he hurried up from the pavilion to the workshops. Kapenta rigs motored home steadily; I could see their craning necks and long-reaching nets. They evoked a brood of ancient herons. As they pulled up onto the island, I could hear the men who crewed the boats shouting to one another. They were calling out the night’s catch in high, singing voices and I envied them.

Mapenga was saying to the lion in a steady, laughing voice, “Mambo Jambo, boy. How’s the lion? Mambo, my boy. How’s Mambo?”

I got up and lit the stove to make tea. K came back from his early-morning prayer session. He looked, as he often did after being with God, as if his face had been lightly glazed—a sort of peeling shine glowed off his cheeks. He put his arm over my shoulder and asked if I was okay.

“Fine.”

Mapenga shouted to me that he’d like some tea, if I was making some anyway. K asked for hot water and honey. I cleared a place from the debris of last night’s supper (wineglasses, the remains of a fish skeleton seething with greasy ants). Mambo came to the wire and took a few, halfhearted swipes at the laundry I had hung up over the top of the cage. He needed breakfast.

The routine of tea, the casual domesticity, the drying underwear on the fence, the unfed cat, the two-o’clock-in-the-morning quarrels, the implied apology, the unwashed dishes.

From a distance, whatever this was could easily be mistaken for a marriage.

The Big Silence

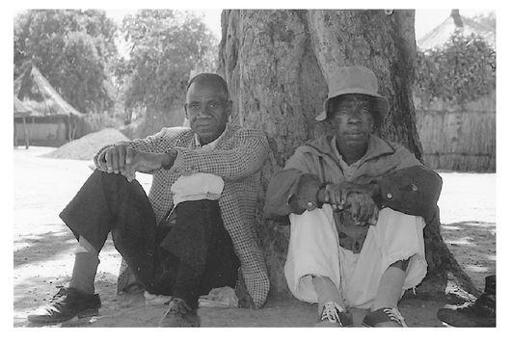

The Elders

MUKUMBURA IS WHERE K was stationed when he wasn’t on patrol. It was where he came to relax from the war. Once a month he left the bush and came back to Mukumbura to sleep and get drunk and clean his gun and have a shower. And to account for every round fired in the last three weeks.

“Bullets aren’t free, man. We need a gook for every round.”

Then he was issued with fresh ammunition and three weeks’ supply of food and sent back out into the bush with three other men. There, jumpy and cracking, and worn down by the heat and the dirt and the fear and the killing, they shot at everything that moved. Fuck the bullet counter back at HQ.

Mukumbura-by-the-Sea, they called it. But there was no sea. Just a huge, ugly sand dune; a desolate stretch of land that looked as if all the leftovers from the beautiful parts of the country were snipped off and left here in an untidy pile of tailings and scrub. To its north, the silted wasteland sank into a river and thereafter into Mozambique. To the south it roped over rocky knots of land until it stalled in the lush valleys that fell beyond Mount Darwin.

Of all the places we came to follow K’s war, this was the most frozen in time. It was as if the war had stepped away from its desk for a moment, but would be right back. Loops of barbed wire ran along high security fences, which snaked and seared through a uniformly blond landscape. A flagpole poked stiffly from the tired tide of sand. Long, low buildings buckled under a flat glare of sun—green and metallic and hot. These crouching saunas were buildings for men without women, men who had no expectation or need of comfort. The old airstrip was still serviceable, not because of any upkeep since the war days but because nothing had had the energy to ruin it. For nearly thirty years, it had baked itself flatter and firmer. A flock of goats helpfully kept its surface nibbled down to a scrub. A torn, white plastic bag jerked and danced across it.