Sea of Ink (8 page)

Authors: Richard Weihe

Tags: #German, #Biographical, #China, #Historical, #Fiction

43

Many months had passed when he was handed a letter by a stranger who said he was a friend of Shitao’s. He read:

Cousin Bada, I have kept your letter. I have not answered

before

now as I’ve been ill. The same goes for letters I’ve received from other people. Today a friend is returning to Nanchang. I have asked him to bring you this letter, with which I’ve enclosed a small picture. The picture shows the Pavilion of Great Clarity on the bank of a river, surrounded by trees. In the upper half sits an old man in the middle of a bare rock. There is still space on the paper. Would you please add a few words? For me the picture would then be – how should I put it? – indispensable. It would be the most valued treasure in my possession.

Bada Shanren unrolled the enclosed picture and

studied

it for a while. Then he read on:

From everything that I’ve heard, it seems as if you are still skipping up mountains, in spite of your seventy-four or seventy-five years. You are like an immortal! As for me, Zhu Da, I am close to sixty and no longer able to undertake any major activity.

Bada put down the letter, reached for the ink and rubbing stone and took hold of his brush.

He completed the picture with a little waterfall and leaves that emphasized the autumnal mood. Then he painted the following words in the remaining blank space:

Above the Pavilion of Great Clarity bright clouds are opening, infinitely high, as the new register of immortals is carried from the violet chamber. The sky has already unfurled its wings

and nothing of the old dust and muck remains in the world.

When the picture was dry he rolled it up and gave it to a messenger who would be sure to get to Shitao at some point.

44

Nobles and rich men everywhere began to venerate the creations of his brush. He received invitations and was easily

persuaded

when good wine was promised.

Naturally the hosts anticipated that, once sufficiently lubricated and in the right mood, Bada Shanren would reach for his brush and leave behind a magnificent ink drawing. So long as Bada was sober, any

collector

after even just a page from an album with a few drawings would not get a thing. They could place a gold bar under Bada’s nose and still have no success. Thus these people tried other ways of acquiring his pictures, such as pretending they were not keen on his work.

When one evening he was invited to what he thought would be a perfectly harmless drinking session, next to his seat Bada found a bucket full of ink and endless rolls of paper. Paintbrushes of all sizes hung down from the ceiling within his reach.

To begin with he ignored the equipment. They drank lots of wine, laughed, slapped their thighs. He forgot himself.

But much later in the evening one of the men present, who was said to be a famous actor, took the largest brush and started caressing it as if he were stroking his lover’s hair. The brush was the size of a broom and he held it upside down, singing to it in a deep, rattling voice.

His short performance received a boisterous round of applause. Then Bada leapt to his feet and grabbed the brush from the actor. He lowered it deep into the tub, stirring the paint as if it were soup. The host, inwardly delighted, at once fetched one of the rolls of paper and, with the help of some other guests, now put four or five lengths of paper beside one another, carpeting the entire floor.

A mixture of singing and shouting struck up when Bada moved to the middle of the room with the heavy, dripping brush. Now he started, slowly at first, then ever faster, turning around so that the ink flowing from the brush formed a fine compass circle. When the brush had finished dripping, Bada stepped out of the black ring and painted the area of the circle as if he were sweeping a small manège with a broom. In the light of the lanterns the wet ink glistened like varnish.

He immediately painted a second round island next to the first, although as he turned around this time he let the brush tip glide over the paper before filling in the shape with black ink. He continued to paint nothing but circles, some large, some small, one after the other, all of them touching but never overlapping. Gradually the white areas of the paper looked like four-pronged shapes made of curved lines only.

When he had covered all the paper with black balls he hung the brush back on the beam and proclaimed, ‘A sky full of stars.’

But no sooner had he uttered these words than he unexpectedly seized the bucket, which was still half full, and poured the rest of the ink over the paper. It was not long before he had smeared and rubbed the remaining white patches black with his sandals, emitting horrible cries all the while. Some of the guests jumped up and grabbed him by the arm and chest, but Bada shook them off and his voice resounded through the throng of hands: ‘Look, look, the black stars in the black sky! The darkness is a universe!’

45

He was astonished when one day he received a reply from his cousin Shitao, in which the latter expressed his gratitude for Bada’s words above the picture of the hermit. The letter was accompanied by a small roll of paper.

The picture I have sent you is called

A thousand wild dashes of ink, Shitao wrote.

They are the traces of my brush, which I let dance over the paper in delight at your words. I really ought to have painted an orchid or bamboo or a heron, but that would have been like trying to hold a candle to the master. These modest dashes, however, are the genesis of all these things, the joy of the brush. Will we ever meet?

Bada unrolled the picture and let it work on his soul. Dots of ink were connected by fine diagonal lines. The overall pattern looked like the traces of bark beetles on bare wood. In between were coral shapes with nodes or a pattern of just ovals. The only larger coherent mass of colour was at the left-hand margin, consisting of lumpy shapes with very fine branchwork.

When Bada stuck the rolled-out picture to the wall and viewed it from the other side of the room, it had changed. It no longer looked just like a collection of apparently meaningless dots, lines and blobs, but like a section of a garden in bloom with boughs full of fruit, luxuriant round shrubs, wild orchids, a squat, withered tree trunk and branches spread out wide with fine petals.

He could not help laughing.

His cousin had almost put one over on him.

46

Over time Bada was a less frequent visitor to drinking sessions, and after a few years he even kept his distance from them altogether.

With each year that he got older, he found the present less important and flat. Memories of events that lay far back in the past popped up in his mind. He tried to recall how, as a young man, he had thought about the world. He remembered his father’s eyes and his lips, which moved without a word ever falling from them – the father who he always understood nonetheless.

It was the first time he had gone weeks without

painting

. Instead he sat in a corner almost motionless for hours, buried in his thoughts.

He suddenly remembered the balls of ink that Abbot Hongmin had given him. He had never touched them. He found them straight away in a casket. Now he rubbed, for the very first time, the ink of the great ink-maker, Pan Gu. Then he set out a small piece of paper and dipped his brush.

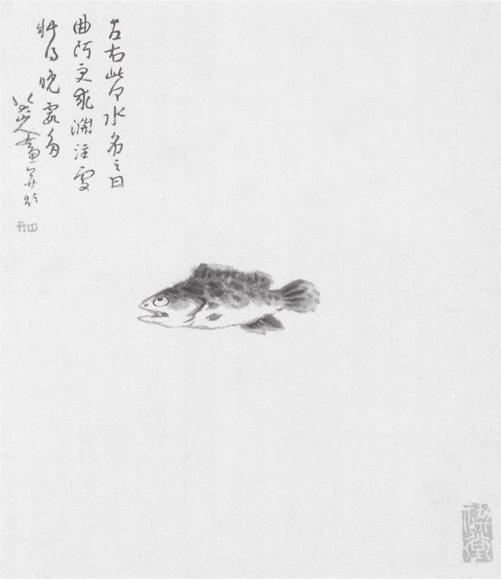

In the centre of the paper he painted a fish from the side, with a shimmering violet back and a silver belly, the tail fins almost semicircular like the bristles of a dry paintbrush. The fish’s mouth was half open, as if it were about to say something. Its left eye peered up to the edge of the paper with an expression combining fear, suspicion, detachment and scorn.

The eye was a small black dot stuck to the upper arc of the oval surrounding it.

The fish swam from right to left across the paper.

Bada painted this one fish and no other, then put his name to the paper.

He had perished long ago, but he was still alive. All he feared now was the drought, when the ink no longer flowed and life had been worn down to nothing.

That is how he saw himself.

Fish

47

As rubbing the ink was increasingly

becoming

a strain, Bada would sometimes just make movements with the dry brush.

And yet he painted every day, even if no pictures were produced.

He was not yet satisfied with his art; he wanted finally to do away with the chattiness of his earlier pictures.

Now he used only Pan Gu’s ink, albeit very thriftily.

How many more strokes could he manage before the last of the ink had been worn away? Innumerable?

Truly, he thought, it is no mere empty saying that ink wears the man down and not the other way round.

Deep night, the oil lamp was smoking.

The sound of heavy rain, the wind rattling the window.

He could not find sleep. He thought of the fine,

polished

jade clasps in his wife’s hair.

Why did this memory never grow old?

48

Or he would dip the brush into a bowl with clean water and paint invisible figures on the paper.

He had set himself one final goal.

He wanted to paint flowing water.

For hours he practised with only the brush and no ink, until his arm hurt. He began in the upper

right-hand

corner, bringing the paintbrush downwards and describing a long curve to the left while reducing the pressure on the brush. Then he let the stroke peter out by slowly lifting the brush and drawing it towards his chest. At the point where the line turned to the left he started a second line which he took downwards,

veering

slightly to the right, then let it run parallel to, and below, the course of the first one, before joining the end of both strokes with a semicircle.

When he had taught his hand these three movements, he put down his brush and for several days carried them out just using his fingers on the blank paper.

He spread out many pieces of paper on his desk. At night, in the darkness, he dipped the tip of his middle finger into a bath of ink and let his finger execute the three curved strokes, without being able to see the traces of ink in the darkness.

He continued like this all night long.

When the first light of morning lit up the desk, a shoal of fish appeared which vanished into the depths of the room.

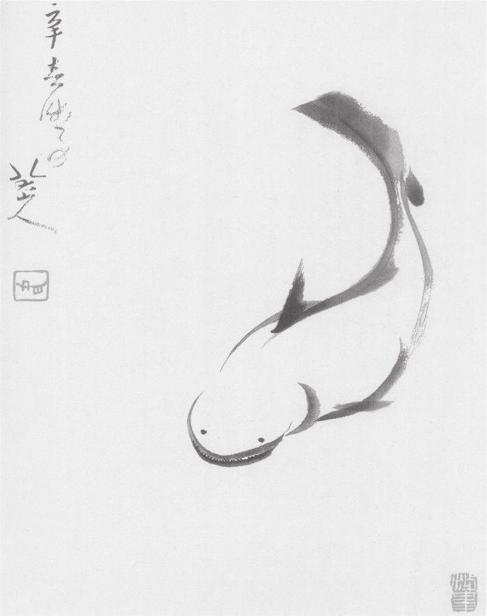

A feeling of great calm flowed through Bada. Slower than ever, he rubbed the ink in the water until he had the right degree of blackness. He dipped the paintbrush and wiped the drops of ink on the peach stone. He closed his eyes and executed the strokes several times over in his mind before putting brush to paper.

Finally, his eyes still half closed in deep

concentration

, from his wrist he let the brush paint a curve to the left, starting as a broad and watery line because of the pressure he applied, then becoming thinner as he lifted the brush. He went over this curve again, just a touch below, and at the end of the first brushstroke he inserted a dash in the form of a pointed sail and, where the second line ran out, a small crescent whose concave side arched to the left.

From the lower point of the crescent he drew two parallel semicircles, one just below the other, reaching to the end of the higher first line. Finally he shaded the narrow white strip between the two semicircles and planted two fat dots to the right and left of the inner edge of the curve.

It had all happened in a few seconds.

Then he put his brush aside, stuck the picture on the wall, and wandered out of the city, up a mountain.

He recalled the master’s words.

If the hand is supple and agile, the picture will be too, and it will move in various directions. The picture does not only show the movement of your hand, it is a reflection of its dance. If the hand moves with speed, the picture acquires vitality; if it moves slowly, the picture acquires weight and intensity. The brush guided by a hand of great talent creates things that the mind cannot follow, which transcend it. And if the wrist moves with the spirit, the hills and streams reveal their soul.

When he returned that evening from his walk, the catfish on the wall looked at him with its tiny eyes.

Bada saw the water and all of a sudden his hand seemed to be a fin.

Catfish