Search the Seven Hills (41 page)

Read Search the Seven Hills Online

Authors: Barbara Hambly

The meal was over. Sixtus lifted his cup, and said, “To the God of Long Shots,” and Arrius, and Varus, and Felix rose to go.

“See me at the praetorian camp in the morning, Professor,” said the centurion, as Alexandres handed him his cloak. Even out of armor, in his dress tunic of scarlet wool, he had the air of danger. He was a storm trooper to his bones. His slow firm tread retreated across the atrium, accompanied by Felix’s high nattering voice complaining about “Leadin’ m’brother astray, an’ all...”

Varus held out his arm, and the burly gardener draped his cloak with the confidence of a master. “We shall be on our way as well, Julianus. Our thanks for the supper. It has been my privilege to dine with a man whose name has been little more than a legend for the last fifteen years. And our redoubled thanks for the part you played in our daughter’s rescue. Tertullia,” he added austerely, “as I wish a word in private with your mother, I beg you grant us a few moments’ leave.”

The prefect and his lady stepped into the shadows of the hallway. Marcus heard their footfalls recede to the dusty reaches of the leaf-strewn atrium, but if they were having a word in private, it was wholly inaudible. As Sixtus seemed to be absorbed in what sounded like a theological discussion with Dorcas, he rose and went quietly to the couch where Tulla still sat, cradling her empty winecup between her hands.

“I know it’s unseemly,” he said softly, “but because of mourning I won’t be able to see you for nine days. I can’t stand it for all that time, not knowing.” He took her by the hand and raised her up, her brown eyes looking up into his. The evening sun had left the garden, and the little summer dining room was almost dark. He led her gently to the narrow door Alexandros had hacked in the vines, to give access out into the dappled cave of the walkway beyond. “I have to know,” he said simply.

She looked down for a moment at his big hands clasping hers and said, “You know my father. I have nothing to say in the matter.”

“That might have been true before...”

“And besides,” she added, her eyes suddenly bitterly ironic in the semi-dark, “it isn’t likely that there’s another man in Rome who’d have me.”

He gaped at her, hurt as though she had struck him.

“I’m sorry,” she said, tears of contrition flooding her eyes, “I shouldn’t have said that.”

“It doesn’t matter! I swear to you.”

She reached up, gathering a handful of toga in one hand and laying the other gently over his lips. “I know perfectly well,” she said softly, “that half the people of our acquaintance are going to be saying—to my face, even—what a noble gesture it was for you to ask for my hand, ‘All things considered.’ And what the truth is will have to remain in trust, between you and me.

“I thought about it, days and nights, lying upstairs in that stinking place. Listening to the noise downstairs. Never knowing what was going to happen next. Listening to them outside the door, talking about killing me. Hoping they would, before I ever had to come back and face the way people would look at me, that awful contemptuous pity people have for victims. I thought I’d rather die than have you ask for my hand to save me from—that.

“But in the midst of all that, in those awful days and nights, you know, I never stopped chipping at that silly board in the window. Even when I thought I’d rather die, I kept on fighting to live. I don’t know what I thought I’d do afterward, but it wasn’t come back. And then Dorcas came. She said you were combing the city, searching for me—not just waiting for me to be found dead or alive. She said that Papa knew where I was, that Papa would help you get me out somehow.”

In the gray evening light her eyes flooded with tears at the memory. As though frozen by a spell Marcus dared not speak, dared not break the train of her thoughts, but he reached out gently to wipe the tears from her face.

“You know,” she went on softly, “hope is about the worst torture there is?”

“I know,” he replied, remembering Sixtus’ words about the comforts of despair.

She reached up, putting her arms around his neck. It had always been a long stretch, and she smiled at the familiar awkwardness between their two bodies. “Marc, if I can trust you—if I can trust the truth of your feelings about me—the opinions of a lot of people I barely know are so much less than that. Can I?”

“Papa?” said Dorcas softly, watching the tall awkward form in the white toga stoop to embrace the small thin shape of the girl. Their shadows blended in the liquid twilight. In the dining room, Alexandras had begun to light the lamps.

Sixtus glanced over at her. “Yes, child?”

“Do you think he knows?”

“I’m sure he’s being very careful not to,” replied the old man calmly. “We’re all skating on very thin ice, my children—my deacons—and getting closer to the edge all the time. He understands as well as we do the need for care.” He looked gravely from her young, serious, triangular face up into the dark scarred face of Churaldin, and smiled, to make them smile. “Not that I didn’t fully expect to end up thrown to the lions in the end, mind you.”

“It isn’t a joking matter.” The Briton seated himself at his master’s feet on the end of the couch, his dark face solemn under the white bandage. “It’s only a matter of time. Some may be willing to take it on trust that the mystery of Christ’s fellowship isn’t evil, though it may be secret from outsiders, but most people hate what they do not know. The emperor’s been very tolerant, but he’s not going to live forever, the way he’s going—and he has no heir. What will happen when someone else takes the throne? What if the next emperor is a monomaniac like Domitian? Or outright insane, like Caligula?”

The Bishop of Rome flexed his injured shoulder gingerly and considered his two young deacons, sitting at the foot of his couch. For a moment something very close to grief seemed to pass across the back of his eyes; then he smiled. “If I seriously wanted to avoid violent death,” he said thoughtfully, “I wouldn’t have become a Christian at all at my time of life, much less a priest, and I certainly wouldn’t have agreed to be answerable for a pack of quibbling lunatics like the Church of Rome. But the future is the future; it is not time as we know it, but a wholeness in the mind of God. And in any case, Christ never said he had been assigned the task of making our lives on this earth more comfortable and pleasant. He came to rip us from our complacency, to shove us—violently if need be—onto the nasty, hard, tedious, confusing, and quite possibly fatal path to God. And beside that, all else, my children, is quite peripheral.”

He looked up, to see Marcus and Tullia standing handfast in the hacked-out archway of vines.

Tullia came forward without speaking and, to Churaldin’s surprised embarrassment, took his face between her hands and kissed him. Then she turned and embraced Sixtus like a father. “Thank you,” she whispered, “thank you all.” She reached out and clasped Dorcas’ hand, and nodded toward her prospective bridegroom.

“He’s

going to be mewed up for the next week, but if you’re free tomorrow, Dorcas, maybe we can meet?”

“All right,” smiled the older girl, “I’d like that. I’ll introduce you to my son, if you’re interested,” and Tullia laughed.

“If you don’t think the Professor here would be jealous.”

“He might,” decided Dorcas, after giving the matter judicious thought. “My boy’s a real charmer.”

Tullia frowned suddenly, as another thought crossed her mind. She glanced up at Marcus. “Didn’t you say a few moments ago that you’d never met Papa, the Bishop of the Christians? Because Dorcas told me that you had.”

Marcus regarded the three of them for a moment: Dorcas in her plain dress, her strong curling black hair already working itself loose from its confining pins, Churaldin with the slave brand on the side of his face, sitting so familiarly at the feet of that frail enigmatic old man—philosopher, scholar, soldier, former imperial governor of Antioch, and perhaps other things besides.

“If I did,” he replied, “no one ever told me who he was.”

The blue eyes met his, startlingly young under white brows. “For one reason and another, people may have worked to mislead you, my son,” he said kindly. “But I have never told you a word of a lie. And I never will.”

Marcus considered him for a moment in silence, meeting the challenge of that calm, heavy-lidded blue gaze. Then he smiled. “I’ll consider myself warned.” He put his arm around Tullia’s shoulders and led her out into the shadows of the hall.

In writing this book I am attempting merely to entertain, not prove any kind of historical or theological point. The only two characters in it with even a remote claim to historicity are Sixtus and Telesphorus, about whom only their names, and the fact that they were the sixth and seventh popes, are known. Otherwise all persons and situations in this book are totally fictitious, and not meant to resemble any modern-day persons, groups, or events.

Even a cursory reading of the writings of the early church fathers will indicate that the early church was a theological battleground. The width of the spectrum of opinions, and the vituperativeness with which the Fathers defended their own opinions and attacked others’, is almost unbelievable to present-day Christians. It is recorded that the Gnostic Christians accused the Catholic Christians of evading martyrdom if they could, but it is likewise recorded that hundreds of Christians in the province of Bithynia flocked to the new magistrate of the province requesting to be martyred. (He sent them away in disgust.) I have attempted to portray the Christians not as plaster saints, but as the upper-middle-class Romans must have viewed them—alarming and incomprehensible.

Most Christian catacombs date from the third and fourth centuries

A.D.

Only two or three of the oldest (including the catacomb of Domitilla) were in use at the time of this story.

When the Temple of Atargatis on the Janiculum Hill was excavated, numerous charred infant skeletons were discovered in its cellars.

Tacitus and Suetonius both refer to the Christians as a sect of the Jews.

All quotes given at the chapter-headings are contemporary.

Barbara Hambly (b. 1951) is a

New York Times

bestselling author of fantasy and science fiction, as well as historical novels set in the nineteenth century.

Born in San Diego and raised in the Los Angeles suburb of Montclair, Hambly attended college at the University of California, Riverside, where she majored in medieval history, earning a master’s degree in the subject in 1975. Inspired by her childhood love of fantasy classics such as

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

and

The Lord of the Rings

, she decided to pursue writing as soon as she finished school. Her road was not so direct, however, and she spent time waitressing, modeling, working at a liquor store, and teaching karate before selling her first novel,

Time of the Dark

, in 1982. That was the birth of her Darwath series, which she expanded on in four more novels over the next two decades. More than simple sword-and-sorcery novels, they tell the story of nightmares come to life to terrorize the world. The series helped to establish Hambly’s reputation as an author of intelligent fantasy fiction.

Since the early 1980s, when she made her living writing scripts for Saturday morning cartoons such as

Jayce and the Wheeled Warriors

and

He-Man

, Hambly has published dozens of books in several different series. Besides fantasy novels such as 1985’s

Dragonsbane

, which she has called one of her favorite books, she has used her background in history to craft gripping historical fiction.

The inventor of many different fantasy universes, including those featured in the Windrose Chronicles, Sun Wolf and Starhawk series, and Sun-Cross novels, Hambly has also worked in universes created by others. In the 1990s she wrote two well-received Star Wars novels, including the New York Times bestseller

Children of the Jedi

, while in the eighties she dabbled in the world of Star Trek, producing several novels for that series.

In 1999 she published

A Free Man of Color

, the first Benjamin January novel. That mystery and its eight sequels follow a brilliant African-American surgeon who moves from Paris to New Orleans in the 1830s, where he must use his wits to navigate the prejudice and death that lurk around every corner of antebellum Louisiana. Hambly ventured into straight historical fiction with

The Emancipator’s Wife

, a nuanced look at the private life of Mary Todd Lincoln, which was a finalist for the 2005 Michael Shaara Prize for Civil War writing.

From 1994 to 1996 Hambly was the president of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. Her James Asher vampire series won the Locus Award for best horror novel in 1989 and the Lord Ruthven Award in 1996. She lives in Los Angeles with an assortment of cats and dogs.

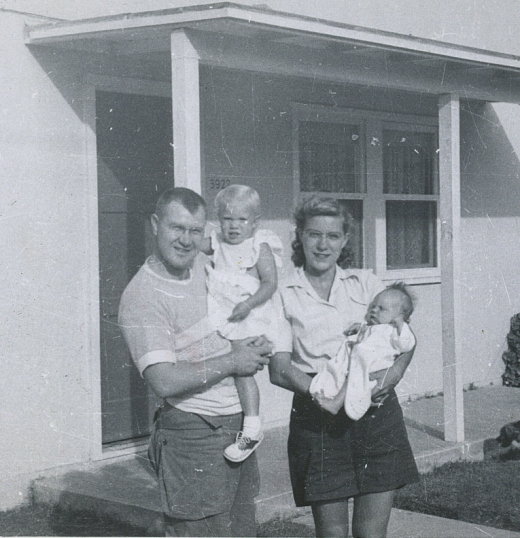

Hambly with her parents and older sister in San Diego, California, in September 1951.