Second Glance (44 page)

The sun was a kiss on the back of his neck, and who knew that an afternoon could be so bright? Ethan picked up his skateboard and carried it under his arm. He walked down the driveway and turned right, then set his skateboard on the pavement and began to roll. A boy on a BMX bike rode past him, wearing a backward, upside-down visor. “Hey,” the kid said, as if Ethan was just like everyone else.

“Hey,” he replied, stoked simply to be having a conversation.

“That’s a bitchin’ board.”

“Thanks.”

“What’s with the winter clothes?”

Ethan shrugged. “What’s with the stupid hat?”

The boy spun his wheels. “I’m heading to the skate park. You want to come?”

Ethan tried to keep his face as blank as he could, but it was hard, being this real. You didn’t truly exist in the world, he now understood, until you could get out and make it take notice of you. “Whatever,” he said indifferently, smiling beneath every inch of his skin. “I’ve got nothing better to do.”

What if she’d kissed him?

After three days now, that question had become unavoidable, caught like a thorn in Shelby’s mind. She relived in excruciating detail the moment where she and Eli had been too close in too tiny a space; what his skin had smelled like, how she had seen the smallest of scars beneath his right ear. She had lain in bed imagining how he’d gotten it: chicken pox, a fistfight over a girl, a fall on the sharp edge of a hockey skate.

Frankie Martine. Shelby supposed when you looked like

that

, it didn’t matter if you had a boy’s name.

She had told herself that, really, she wasn’t jealous. In the first place, she hardly knew Eli Rochert. In the second place, in Shelby’s limited experience, romantic love was selfish— linked to want and yearning. Maternal love was the other end of the scale—all about sacrifice. She had given herself entirely to Ethan; certainly there was nothing left to offer to anyone else. And yet, she wondered if love—as rare a commodity as gold—might not share the same properties, capable of being hammered so thin it might expand exponentially.

Had Eli and Frankie Martine spent the past seventy-two hours together?

Shelby sat at the reference desk, her hands poised over her computer keyboard, as if she expected a patron to come up any moment with a challenging inquiry.

How do our lungs screen

out carbon dioxide? How did the dinosaurs die? How many World

Series have the Yankees won?

She knew all the answers. She was just afraid to ask questions.

But it was dinnertime, and the last visitor to the library had left two hours ago. Shelby had to stay until seven, although no one would come in. With a frustrated sigh, she set her head down on the desk. She could sit here forever, and neither Eli nor Watson would enter.

So when the bell above the library door twinkled, Shelby snapped upright, hoping in spite of herself. “Oh, it’s you,” she said, watching the town clerk stagger in beneath the weight of a yellowed box nearly as large as herself—and that was saying something.

“Well, that’s a fine how-do-you-do!” Lottie huffed, wiping her dirty hands on her skirt.

“It just . . . I was expecting someone else.”

“That gorgeous cop?” Lottie grinned. “I don’t know as I’ve ever seen anything so delicious

and

calorie-free.”

Laughing, Shelby came around the desk and helped her haul the box onto the checkout counter. “Trust me, he’s still bad for your blood pressure. What’s this stuff?”

“We had the boiler replaced yesterday—and found about thirty boxes of records no one even knew existed . . . which tells you how old that boiler was. Anyway, I know you were looking for things from the 1930s. I thought maybe you and your detective might want to sort through them.” She raised a brow. “You could make a night of it.”

Shelby opened the top of the box, coughing as the dust flew. Inside were dozens of rolls of paper. “Blueprints?” She reached inside and began to unroll one, using two Hardy Boys mysteries to anchor the ends.

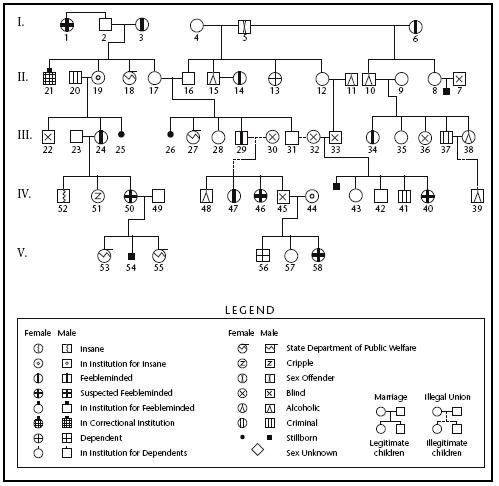

PEDIGREE CHART

of the

WILKINS FAMILY

Eugenics Survey of Vermont,

1927

The key seemed to link alcoholics and cripples and sexual offenders and illegitimate children and criminals. Shelby peered closer at some of the symbols.

In Institution for Feebleminded.

Feebleminded. Suspected Feebleminded.

Oddly, the records were curled into a clock-dial format, so that it seemed that all of these social ills were spreading with subsequent generations, and rooted to the two unfortunates in the center who’d married and procreated. A second chart, a bar graph, reorganized the family by “Social” and “Unsocial” individuals, according to the legend.

Social: Those who seem to be desirable citizens—law-abiding, self-supporting,

and doing some social work. Unsocial: insane and suicides.

Undetermined: Those who, while not definitely showing either of the

defects, do not seem to show any socially desirable tendencies, and those

about whom too little is known to make any judgment possible.

“Lottie,” she said, “where did you find this?”

She unrolled a second chart on top of the first. PEDIGREE OF A GYPSY FAMILY, THE DELACOURS. A handwritten message floated down to the floor. “Tell Harry—sex-deficiency seems to be holandric. Perhaps use charts in hearings for Sterilization Bill?” The stationery was printed at the top: Spencer A. Pike, Professor of Anthropology, UVM.

The box was filled with more genealogies and correspondence and index cards written in a careful hand, which seemed to be case studies of the people who had figured into these pedigree wheels: Mariette, a sixteen-year-old girl at reform school, had a history of petty larceny, an inability to control her temper, an abnormal interest in sex, and a slovenly disposition. Oswald had dark skin and shifty eyes, had retained his tribe’s roving tendency, and—as a result of an “illegal union,” had produced seven subnormal children in as many years. Shelby pulled out the Fourth Annual Report of the Vermont Committee on Country Life. It fell open to a dog-eared page, an article cowritten by H. Beaumont and S. A. Pike. “Degenerate traits do not breed out,” Shelby read aloud. “But they may be held at bay and diluted with a favorable choice of mate.”

“Eugenics,” Lottie read, holding up another annual report. “What on earth is that?”

“It’s the science of improving hereditary qualities by controlling breeding.”

“Oh, you mean like they do for cattle.”

“Yes,” Shelby said, “but these people did it to humans.”

Eli had gone off duty at nine, but years ago he’d made it a habit of doing a final check before he went home—sort of like tucking his town in for the night. Normally, when he felt like things were settled, he’d drive back to his place . . . but tonight, with Cecelia Pike’s murder weighing on his mind, he just didn’t feel like his work was finished.

He drove aimlessly down the access road to the quarry, Watson at his side. Solving this case wasn’t going to get him a citation. It wasn’t going to bring Cissy Pike back to life. And no prosecutor was going to try a nonagenarian with advanced liver disease. So why did any of this matter?

Watson turned and butted Eli on the arm. “It’s too cold out. I’m not rolling down your window.”

The answer was: Cissy Pike had gotten him thinking. About what it meant to belong—to a family, to a lover, to a heritage—and what it cost to hide the truth. He knew, as a detective, that even people you thought you knew could surprise you with their actions. But it turned out that you could surprise yourself, too.

Eli wanted to go to the ceremony that Az Thompson would perform to gather the remains of Cissy Pike and her child. Not because he was a cop involved in the case . . . but because, like her, he was half-Abenaki. And because, like her, he knew what it felt like to keep that hidden.

Watson sidled closer on the seat, burrowing his nose in the neck of Eli’s shirt. “All right,” he conceded, and opened the window. Watson liked driving that way, the wind flapping his loose lips up and down like small wings. Suddenly, he raised his nose and began to howl.

“Jesus, Watson, people are sleeping.”

The dog only keened a higher note, then stood up on the seat and began to wag his tail in Eli’s face. Faced with the possibility of driving off the road, Eli pulled over. Watson leaped through the open window as they rolled to a stop, and loped to the fence that surrounded the eastern wall of the quarry. He started to bark, then stood on his hind legs and caught his claws in the chain links as someone on the other side stepped forward. The kid was wearing gloves. It was cold out, but not

that

cold. Squinting, Eli tried to make out a face beneath the brim of the baseball cap, but all he could see was skin that glowed as white as the moon. “Ethan?” he called out.

The boy’s head came up. “Oh,” he said, deflating before Eli’s eyes. “It’s you.”

“What are you doing here? Who let you into the quarry?”

“I let myself in.”

“Your mom know you’re here?”

“Sure,” Ethan said.

Eli knew that the quarry was blasting tomorrow at dawn—they always let the police department know, for the sake of safety—and that having Ethan in the vicinity of explosives was not a good idea. “Climb over,” he ordered.

“No.”

“Ethan, it’s just as easy for me to haul ass over the fence and get you myself.”

Ethan took a step back, and for a moment Eli thought he would bolt. But then he tossed his skateboard into Eli’s hands, and hurtled toward the chain-link. Scrambling effortlessly as a spider, he dropped to the ground beside Eli and held out his wrists. “Go ahead. Cuff me for trespassing.”

Eli stifled a smile. “Maybe I’ll break protocol. I’m assuming this is your first offense.” He started walking to the car. “Want to tell me how you wound up here?”

“I went outside and just kind of kept going.”

Eli looked down at the gloves on Ethan’s hands again.

“Didn’t she tell you?” the boy said bitterly. “I’m a freak.”

“She didn’t tell me anything.” Eli pretended that he couldn’t care less whether Ethan chose to continue the conversation. He dropped Ethan’s skateboard, walked to the back of the truck, and whistled for Watson. “Well. See ya.”

The boy’s mouth dropped open. “You’re leaving me here?”

“Why shouldn’t I? Your mom knows where you are.”

“You mean you believed me?”

Eli raised a brow. “Is there a reason I shouldn’t?”

In response, Ethan threw his skateboard into the pickup and got into the passenger seat. Eli started to drive. “When I was born, my fingers were webbed together.” He felt Ethan’s gaze shoot to his hands on the steering wheel. “The doctors had to cut them apart.”

“That’s gross,” Ethan said, and then he blushed. “Sorry.”

“Hey, you know, whatever. It’s just the way I was made. Didn’t keep me from doing what I wanted to do.”

“I have XP. It’s like being allergic to the sun. If I go out during the day, even for a minute, I get burned really badly. And it

does

keep me from doing what I want to do.”

“Which is?”

“Swim in a bathing suit and dry off in the sun. Take a walk outside during the day. Go to school.” He glanced at Eli. “I’m dying.”

“So’s the rest of the world.”

“Yeah, but I’m going to get skin cancer. From all the exposure to the sun before anyone knew what I had. Most kids with XP die before they’re twenty-five.”

Eli felt his stomach tighten. “Maybe you’ll be the one who won’t.”

Ethan stared out the window for a few miles, silent. Then he said, “I woke up early, and no one was around. So I went outside. Hung out at the school, skateboarding. But then the other kids had to go home, to bed. And I wasn’t even tired, because I’d been sleeping all day. I just kept walking, and I wound up here. I’m a freak,” he repeated. “Even when I try, I don’t fit in.”

Eli turned to him. “What makes you think it’s different for anyone else?”

Ross had fallen asleep over the keyboard, where he was currently inventing a ghost. He woke up, ran his tongue behind his teeth, and tasted despair. Even after brushing and rinsing with Listerine he still couldn’t shake it—bitter as licorice, with small crystals that melted on the tongue and left it the sunset color of hopelessness. Grimacing, he padded downstairs to the kitchen to pour a glass of juice and realized he’d forgotten about Ethan. It was nearly midnight—and his nephew would have been up for hours.