Secret sea; (9 page)

Authors: 1909-1990 Robb White

Pete was so mad that he was shaking when he got to his feet. The boy stopped, let the loaf of bread fall, and drew back his right arm, the can of beans shining in his hand.

Slowly then Pete began to grin. He thought of himself—a strapping six-footer, a big hero with a Navy Cross—knocked silly by a street urchin.

"Okay," Pete said. "Go heat 'em up in the galley."

The boy relaxed his arm just a little. His eyes watched Pete warily from under the tangle of hair.

"Fm licked," Pete said. "Go heat your beans."

The boy suddenly smiled. Pete was surprised at the shyness of it and at the way the toughness disappeared.

The boy put some coal on the Shipmate stove and put the two cans of beans into a pan of water.

"Don't want you to think I'm stingy," Pete remarked, "but can you eat two cans of beans?"

The boy looked around. "Why not?"

Pete shrugged. "Lots of beans."

The boy pointed at his stomach. "Big hole." 90

MIKE

"Go right ahead," Pete said.

The boy picked up the coffeepot and shook it, hstening to the coffee sloshing around.- "Hah," he said, *7oe."

"What?"

"Jamoke. Java," he said, putting the coffee on the back of the stove. "Gut rust."

"What'd you hit me with?" Pete asked, leaning back against the drainboard.

The boy silently held up his fist and then one foot, shod with the heavy Army shoe.

Pete inspected the fist, then the wrist and arm and shoulder. In the rags and tatters the boy looked small and helpless, but Pete discovered that he had a wide, flat pair of shoulders under the baggy shirt, slim hips, and a boxer's legs.

"How old are you?" Pete asked.

"Let's don't get personal, Mac," the boy said.

"My mistake." Pete looked at the boy's back. "Ever worked around boats?"

The boy swung around. "Listen, nosy, for two lousy cans of beans I don't get grilled, see?"

"You're an unpleasant little citizen," Pete remarked.

The boy's eyes were glittery and hard as he surveyed Pete. "What do you expect for two cans of beans, mate, true confessions?"

"Skip it," Pete said. "I thought perhaps you had the instincts of a human being."

The boy turned back to the stove and poked

SECRET SEA

his dirty finger down into the water. He flipped the cans out, opened one of them, and hoisted himself -up on the shelf. Then, carefully, he began eating, pouring the beans out in gobs on slices of bread. He was making quite a mess of himself and the environs.

Pete got a big spoon out of the drawer and held it toward him. **New invention,'' Pete said.

The boy took the spoon. "Oh, a pantywaist," he said.

The first can of beans went down with hardly a swallow, and he opened the second can. In a very short time he had eaten all the beans and a loaf of bread. Wiping beans around his face with the back of his wrist and hand, he got down off the shelf.

"What time do you eat breakfast, mate?"

Pete looked at him. "Listen, horrible," he said slowly, "from now on you keep off this boat."

"Some eggs would be good," the boy said. "I haven't ate a egg in a long time. Eggs, sunny side up, and bacon—for me."

Then he walked out through the cabin, up the companionway, and across the deck. Pete went topside in time to see him rowing away in a boat which had once been a small crate but now had enough tar in it to keep it from leaking too badly.

Blood On The Faceplate

JL ete went ashore early in the morning. As he rowed up to the stinking, dirty wharves, he looked for the excuse of a boat the boy had used but didn't see it. Pete had locked up every hatch

SECRET SEA

and port on the Indra and he hoped that the dirty urchin wouldn't break a skyhght to get another can of beans.

The first thing he did was call Mr. Williams.

"Weber showed up last night," Pete said.

"Where?"

"Can you see a black sloop about fifty feet long down in the basin?"

"Yes. I see it. Is that Weber's?"

"Yes, sir."

"I'm not surprised, Pete. That's his only play now. Since he hasn't been able to get the log, he can only follow you. What are your plans?"

"I sneaked out last night. He knows I'm gone, but I don't think he knows yet where. I'm way down the bay, anchored in the stream."

"Good work."

"I'm going to scour the beach today and get somebody to go with me if I have to shanghai a man. Then I'll get out of here on the tide tonight."

"Weather's making up . . . but I guess you'd better get out to sea as soon as you can."

"I'm going to. I'll let you know what progress I make."

"Good luck."

Then Pete called up the hospital where John was and sat in the bad-smelling phone booth until he heard Johnny's voice.

"Hello, Jawn. How you coming?"

BLOOD ON THE FACEPLATE

"Pete? Is that you, Pete? Listen, you know what I can do?"

Johnny's voice sounded very excited and Pete could hear him half laughing.

"What can you do?" Pete asked.

"I can wiggle it, Pete. Honest. I can wiggle it back and forth."

"Wiggle what, Jawn?"

"My thumb. My right thumb. You ought to see it. Just as easy."

Pete didn't know why that hit him so hard. A fourteen-year-old boy could—wiggle his right thumb.

"Good work, Jawn. How're they treating you?"

"Fine! I get sort of tired of all the things they do with me, but I can wiggle my thumb now. So I guess they're all right."

"Stay with 'em, boy."

"When are you going to sail, Pete?"

"Not for a while yet, I guess. Got a few more things to do."

Johnny's voice was suddenly slow. "I wish I was going with you, Pete."

"Next time. Give Maw my love."

"I will. Be careful, Pete. You know why," Johnny said.

It was late in the afternoon when Pete Martin trudged back down to the wharves. He felt tireder than he ever had in his life and com-

SECRET SEA

pletely defeated. He felt angry, too, as he remembered the way men had laughed at him when he had asked them to sign on as a hand aboard the schooner. And he felt sorry for the men who had asked to go because the only ones who had asked were just hulks of men, derelicts, drunks, bums, and drifters who only wanted a place to sleep and something to eat. Pete had listened to them all, but not one of them was able-bodied enough to go to sea.

He called up Mr. Williams from a hash house and told him what had happened.

"Too bad, Pete. But the black sloop is still in her berth. Weber and his men have been gone since noon. .. . Whoa, here they come now. They're getting aboard her. Looks like something has happened to one of them—he's got a bandage on his head and the others are helping him aboard."

"Is it Weber?"

"No, it's one of the others. Anyway, Pete, with this storm making up you might as well sit it out in the bay."

"All right," Pete said. "I'll wait unless Weber makes a move."

Pete went out into the darkness, climbed down to his rowboat, and rowed slowly out toward the Indra, his back to her, his eyes looking at the white city.

When he bumped against the Indra he turned, 96

BLOOD ON THE FACEPLATE

threw the painter around the mainsheet bitt, and swung himself up on deck.

The first thing he saw was the new, bright scar on the mahogany hatch of the companionway. The hasp of the lock had been torn off, and the door lay back, both hinges broken.

On the deck, as Pete ran toward the companionway, were drops of blood.

Pete swung himself down the steep companion ladder and stopped in the doorway of the main cabin.

It looked as though a hurricane had swept through the interior of the boat. Books, charts, instruments littered the deck. All the diving gear had been taken down and thrown to one side. Looking through into the galley and his cabin, he saw that the same thing had happened forward.

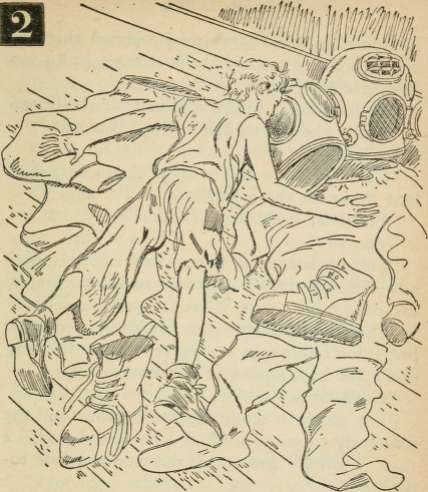

Pete flipped on the overhead light and stepped into the cabin. Lying between the two diving suits, which looked almost like the collapsed bodies of men, was another body. Pete recognized the ragged khaki shirt, the baggy pants.

The boy was lying awkwardly, his neck twisted back and his face down on the faceplate of the heavy helmet. In the light Pete saw blood running very slowly across the glass faceplate and on down the polished metal helmet.

Remembering his instructions in the Navy not to move a man if there was any chance that his

SECRET SEA

back had been broken, Pete stooped and felt for the pulse in the limp wrist and then he saw the faceplate cloud with the boy's breathing. Pete moved first one arm and then the other and then the legs. There was no catch in the limp, dead movement. Then, very carefully, he moved the head and at last lifted the boy up, convinced that the backbone and neck were intact, and carried him into his own cabin. There the mattress and bed clothes had been yanked off and thrown on the deck.

Pete put the boy down on the mattress and got a wet cloth from the kitchen. Swabbing back the matted, dirty hair, he saw a very ugly purple welt across the face from the temple down almost to the mouth. The skin had been smashed open at the cheekbone and was still bleeding.

Pete got the first-aid kit and put a sulfa powder dressing on the boy's cheek. He was looking for any other wounds when the boy came to and began to struggle. Pete put his hand on his chest and held him down.

"Take it easy, mate," he said.

The boy raised his head. **Where'd they go?"

"They've gone."

The boy settled back and put his hands to his forehead. He groaned a little and then opened his eyes. "You shoulda been here," he said.

"What happened?"

BLOOD ON THE FACEPLATE

The boy tried to sit up, and Pete helped him get his back against the soHd bunk.

**I thought it was you," the boy said, taking time out to feel around inside his mouth with the end of his tongue. "Thought Fd come out and chat a while. When I got on board, I saw how the hatch had been broken open. So I sneaked down into the cabin, and there were two joes taking the place apart. I went back to the lazaret and got a marlinespike and came back to the cabin.

"They were really wrecking the place. I sneaked along the bulkhead there." The boy pointed into the main cabin. "I let one of them have it with the marlinespike and went for the other one when the first one let out a grunt. I was doing fine until the third one came out of the galley. I only saw him for a second—a tall, skinny drink of water—before he slapped me in the face with a pistol."

"You're going to have a first-class shiner," Pete said. "What did the skinny one look like?"

"I hardly saw his face. I was watching the barrel of that gun." The boy pushed himself up with his hands and got to his feet. He held his head in both hands. "See any cracks in my head?"

"No. Just where he walloped you."

The boy looked out with his good eye from under the tangle of hair. "What were they looking for, mate?"

"For something they'll never find," Pete said 99

SECRET SEA

slowly. **Something that is only in my memory."

''Good thing they didn't get in there. Look at the mess!"

Pete sat down on the framework of the bunk and looked into the main cabin.

Weber was closing in on him—fast. Pete knew that his only way of escape was the open sea.

He looked speculatively at the boy. The kid was certainly a scrapper. No one had asked him to take on Weber's gang singlehanded. And under all the dirt and matted hair the kid had intelligence in his eyes. Maybe, Pete thought. It's a long chance but I'm desperate now. I've got to get out on open water.

"How you fixed for beans, mate?" the boy asked.

"Would you settle for a steak dinner?"

The good eye looked suspicious. "Don't kid me, Mac."

Pete looked at him. "Son, I'm in no mood to kid anybody. Come along."

"Where are we going?"

"Ashore," Pete said.

When Pete tied up at the wharf, he told the harbor police what had happened and asked that they keep an eye on his boat for the next few hours. Then he took the boy into the nearest decent steak house. Across the table, with the linen tablecloth, the boy looked very much out of place in his ragged clothes and with the uncut

BLOOD ON THE FACEPLATE

hair. When the waiter came, frowning, Pete gave him fifty cents and ordered two steak dinners. Then he waited until the boy was half through wolfing the food before he said, "How would you like to sail with me?" "Sail where?" "Gulf."

"What's in it for me?"

"Maybe a thousand bucks, maybe nothing." "What's the gag?" "I need help, that's all," Pete said. The boy ate two or three huge mouthfuls before he looked at Pete again. "Do you mean that, mate?" he asked, his voice low. Pete nodded. "I eat every day?" "Three times," Pete said.

The boy put his knife and fork down on the clean tablecloth, pushed back his chair, and said, "Let's go."

"Hold hard," Pete said. "What about your parents? Will they let you?"

"I ain't got any parents, Mac. And nobody can tell me whether I can go or not, see?"