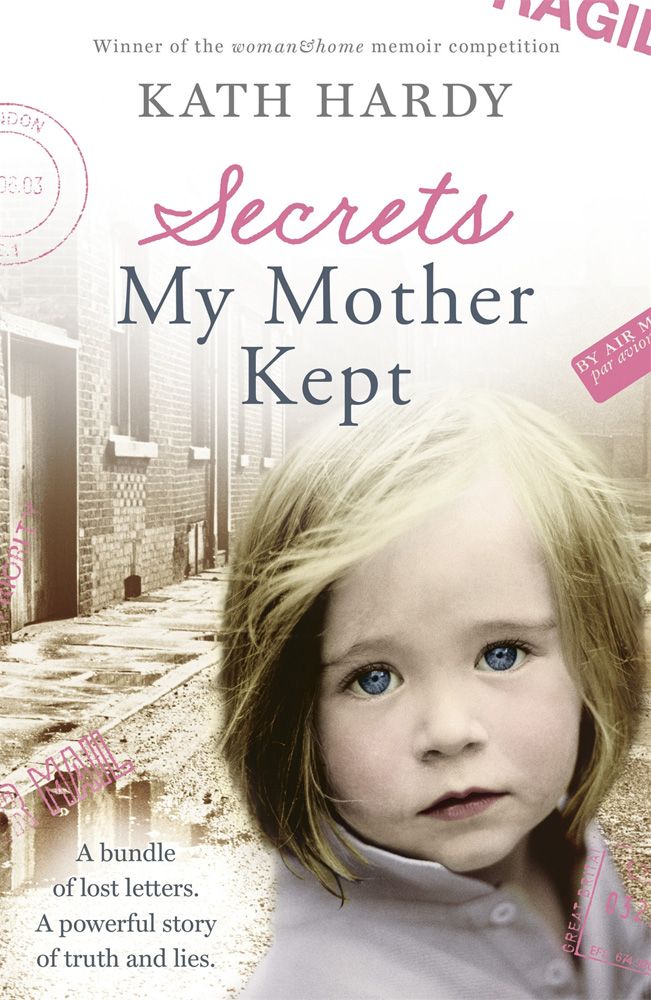

Secrets My Mother Kept

Read Secrets My Mother Kept Online

Authors: Kath Hardy

Kath Hardy

Kath Hardy grew up on a council estate in Dagenham in the 1950s and 60s, the second youngest of ten children. She was a teacher for more than 30 years, before becoming an education advisor. She now lives in Suffolk with her husband, and has two grown-up children.

Secrets my Mother Kept

Kath Hardy

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette UK company

Copyright © Kath Hardy 2013

The right of Kath Hardy to be identified as the Author of the Work

has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any

means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be

otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that

in which it is published and without a similar condition being

imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 444 76326 3

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

To Mum and Aunty, the towering forces in my life, who both in their own way shaped me into the person I am today.

Contents

11 Aunty, Mum and the Empty House

16 Getting Ready for Big School

40 A New Flat and a New Romance

59 A New Home and a New Sadness

61 Fitting the Jigsaw Together

Prologue

I remember wishing it wasn’t so cold, but at least the sun shone through the breaks in the clouds.

‘The sun shines on the righteous,’ Aunty used to say.

It was four weeks since Mum had died. Standing still and straight next to my siblings, I thought of those who were missing: Marge, Marion’s identical twin, and Mary, a year older, both in Australia with their families; my secret sister Sheila in the Isle of Man . . .

The priest stood next to the grave and said the prayers of internment in a soft clear voice. Mum was cremated soon after she died and now we were burying her ashes on the small family plot, next to her mother and father and older sister ‘Aunty’. The only marker was a small plain wooden cross and the plot was overgrown with rough grass. I wished we had decided to scatter her ashes somewhere beautiful and not in that barren East London graveyard with its dilapidated statues and neglected monuments.

No one was crying except for me, and I wasn’t crying for Mum, I was crying for myself.

I had begun to notice the changes in Mum during my weekly visits. She had lost weight, and was shrunken and grey. She had never had many wrinkles, but now her eyes were old and tired, and although she was only seventy-three, she looked frail and ill.

‘Kath,’ she said softly as I took her up a cup of tea, ‘I need to clear out the cupboard in here.’

I looked at her lying in that bed and, to my shame, felt angry. In a few weeks I was having an operation – a serious one. It was my turn to be ill now; I needed her to look after me. Why was she talking about tidying the cupboard? It was blocked in by the wardrobe and no one had opened it in years.

‘Mum, can you drink this?’ I offered her the cup, but she turned her head away. Mum’s bed was in the box room. I had slept most of my childhood nights in that room. First my sister Mary and I had slept together in a big double bed that took up most of the room. Once Mary had left home I shared the same bed with Mum. I used to dread the rare occasions when I was told to change the sheets because I didn’t like to see the black speckles of mould that bloomed where the sheets touched the damp walls. There was a large air vent in the external wall but Mum covered it in plastic bags to stop the draughts and I guess that was why the walls were always running with moisture. The bedroom window looked out over our street, Valence Avenue. It was one of the main through routes in Dagenham. It was lined with tall horse chestnut trees, which we would scramble under every autumn searching for conkers.

Inside, the paintwork was peeling, and there was never any carpet on the floor, so when I got out of bed in the mornings my toes would freeze. As well as a double bed there was an old 1930s-style wardrobe and dressing table that had been donated by a well-meaning relative, and squeezed into the remaining space. These held a strange mixture of my things and Mum’s and smelt of mothballs and damp. I still dream about that smell, and that room.

After Mary had left home she would sometimes send little presents home for Margaret and me. A pair of socks, a bar of soap, a flannel – small things, but I treasured them. We didn’t really have things of our own, so I would squirrel these treasures away in my drawer of the dressing table. I never used any of them – they were far too special to use – I just got them out to touch and look at from time to time. There was no light bulb attached to the fitting that dangled from the centre of the ceiling because Mum couldn’t afford to replace it. Consequently homework had to be done sitting at the top of the stairs under the landing light. Downstairs was always much too noisy and busy and there was never any room for books.

As I stood in that room as an adult, it seemed to me that for all the happy memories, the walls were permeated with secret sorrows.

I hadn’t got round to sorting out the cupboard while Mum was alive, but several months after the funeral I agreed to help my older sister Josie clear Mum’s room. She and our sister Pat had never married and still lived in our old childhood home.

We began to sort through all the assorted junk and paraphernalia. Josie was looking hot and flushed, and I was worried about her.

‘Are you sure you’re okay, Josie?’ I asked. ‘We can stop for a rest if you like.’

She shook her head.’ No, I’m fine.’

Her hair was fine like Mum’s had been, but she dyed the grey. Josie had always been a very neat person, and was usually well groomed and conscious of her appearance. Her fingernails were always manicured and her hair perfectly styled. The one thing she had never been able to control was her weight, and it was this that was now making her breathless.

Cobwebs dangled from the top and sides of the cupboard, and my mind spun back fourteen years to when I had not long been at college, and my jewellery box mysteriously disappeared from the dressing table. Patrick, my then boyfriend, had bought me some large gold hoop earrings for my twenty-first birthday, a gold ingot pendant and some pretty gold and silver bangles. When I had questioned Mum about it she told me she had put the box in the cupboard to keep them safe. At the time I’d believed her totally, and it was only later that I realised that she must have sold them. Still, I watched closely as Josie groped about in the cupboard.

‘What’s this?’

She reached to the back of the shelf and pulled out a dusty old bag full of yellowing envelopes. They were all written in the same unfamiliar sloping hand, all with different postmarks, some dated from before I was born, but all addressed to me, Kathleen Stevens. I swallowed as I realised that she’d found something far more precious than that old jewellery box. Something that would have the potential to change my life; to help unravel the mysteries that had dogged it.

1

The Mummy Lady

Thinking back now, my memories of Dagenham began towards the end of the 1950s. I remember a patch of blue sky and someone singing ‘Lulla Lulla Lullaby’ in a soft, sweet, sad voice. I don’t know how old I was, or who was singing, but the melody, though simple, was haunting. Rationing had ended several years before, and food was plentiful for those who could afford to buy it. However we were poor. Crushingly poor. We lived in the same house that our grandparents had moved to in the 1920s, but Dagenham had already begun a downward slide. The once well-kept red brick houses were starting to deteriorate, and many of the original tenants had moved on.

I don’t suppose growing up as the second youngest in a single-parent family of ten is ever a bowl of cherries. Trying to do that as a Catholic in 1950s Dagenham was even harder. Pat was the oldest sister I knew, and I loved her to bits. She had shiny black hair and twinkling brown eyes that I could see through her glasses. To me she was all powerful; her strong arms kept me safe and she knew the answers to all my questions. Well, nearly all. I remember her taking me on a special visit one day. I suppose I must have been about three and my only younger sibling, Margaret, would have been about eighteen months old.