Secrets of the Wee Free Men and Discworld (4 page)

Read Secrets of the Wee Free Men and Discworld Online

Authors: Linda Washington

When Granny Weatherwax and Magrat argue (an inevitability when they get together), each deciding that a person needs more brain or more heart (page 165 of the paperback edition of

Witches Abroad

), you can't help thinking of what the Scarecrow and Tin Man each thought he needed.

Witches Abroad

), you can't help thinking of what the Scarecrow and Tin Man each thought he needed.

During the argument, Nanny notices that the road to Genua is paved with yellow bricksâan allusion to the yellow brick road leading to the Emerald City of Oz. Genua even sparkles like the Emerald City.

Still another nod to

The Wizard of Oz

comes in

Moving Pictures,

where an actor describes the plot of the clickâor movieâhe's working on as “going to see a wizard. Something about following a yellow sick toad.”

28

The Wizard of Oz

comes in

Moving Pictures,

where an actor describes the plot of the clickâor movieâhe's working on as “going to see a wizard. Something about following a yellow sick toad.”

28

But an oblique reference to

The Wizard of Oz

(possibly) can be found in

Pyramids

, when the Sphinx tells young Teppic, “Thou art in the presence of the wise and the terrible.” The fake wizard of Oz described himself as “Oz, the Great and Terrible.”

29

The Wizard of Oz

(possibly) can be found in

Pyramids

, when the Sphinx tells young Teppic, “Thou art in the presence of the wise and the terrible.” The fake wizard of Oz described himself as “Oz, the Great and Terrible.”

29

Â

Â

Even with such building blocks, Pratchett still needs the best patching materialsâhis imagination, skill, and humorâto ensure that the three purposes of good architecture are fulfilled.

That concludes this leg of the tour. Please notice the tip jar on your way out.

Fully Realized Worlds

Discworld works because it takes itself seriously. The people in Ankh-Morpork don't think they're being funny.

âTerry Pratchett at an October 12, 2006, book signing (Anderson Bookshop, Naperville, Illinois)

S

ome fantasy worlds can seem as real as your backyardâalmost like you could step into it the moment you open the book. Worlds like â¦

ome fantasy worlds can seem as real as your backyardâalmost like you could step into it the moment you open the book. Worlds like â¦

Â

The Star Wars Galaxy (various planets

“a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away”)

The incredibly popular film series created by George Lucas chronicled the rise of the Galactic Empire and spawned many series of books written by authors as disparate as Terry Brooks, Jude Watson, Elizabeth Hand, Troy Denning, Kathy Tyres, R. A. Salvatore, Michael Stackpole, and many more.

Lucas came up with the mythology of the various planets (Tatooine, Naboo, Alderaan, Dagobah, and others), cultures, and characters like Luke Skywalker, Anakin Skywalker, Yoda, Han Solo, C3PO, and so on, and revolutionized the movie industry as well as science fiction in general.

Â

Middle-earth

In his quest to develop a mythology for England, Tolkien created a mythical place that seems like an actual place in history. The moment you walk into Bilbo Baggins's hobbit hole in the Shire and trek through the region of Eriador all the way through Mordor, you get a

sense of being in a believable world. (And after the movies, beautifully realized by Peter Jackson and hundreds of craftspeople, Middle-earth seems even more real.)

sense of being in a believable world. (And after the movies, beautifully realized by Peter Jackson and hundreds of craftspeople, Middle-earth seems even more real.)

Like Pratchett, Tolkien was inspired by Norse mythology. Middle-earth is Midgardâthe home of men in Norse mythology.

Â

Pern

Anne McCaffrey has multiple series that take place on Pern, a planet in the Rukbat System. This planet's Earth-like environment came at a price for settlers, thanks to the threat of Threadfallâthe silver spores deposited by an orbiting planet, Red Star. Because the Thread attacked all organic matter, the technologically advanced society returned to a medieval state. Only dragonfire could stop the Thread.

Kahrain, Araby, and Cathay were just a few of the provinces established in the first landing. The society became divided among the weyrs (the homes of the dragons and their riders), the holds (lord-ruled lands), and the halls (those of craftspeople). The series continues under the pen of McCaffrey's son, Todd.

Â

Arrakis/Dune

Frank Herbert's award-winning epic series (now known as “classic

Dune

”) of political intrigue in space took place on the desert planet Arrakis, a fiefdom run by the House Atreides. Arrakis, populated by Fremen and sandworms, was the place for melange, a spice valued throughout the universe. The Fremen searched for their MessiahâMuad'Dibâwhile House Atreides and House Harkonnen battled each other for control of Arrakis.

Dune

”) of political intrigue in space took place on the desert planet Arrakis, a fiefdom run by the House Atreides. Arrakis, populated by Fremen and sandworms, was the place for melange, a spice valued throughout the universe. The Fremen searched for their MessiahâMuad'Dibâwhile House Atreides and House Harkonnen battled each other for control of Arrakis.

The series began in 1965 and after Herbert's death was continued by his son, Brian, and Kevin Anderson.

Â

Earthsea

Ursula LeGuin's archipelago of islands (Gont, Roke, Karego-At, Atuan, Havnor, etc.) is the setting where magic and mayhem abound. In A Wizard of Earthsea to The Other Wind and books of Earthsea short stories, LeGuin showed the history of Earthsea from the Creation of Eá through Ged's birth and rise from wizard to archmage to Tenar's adoption of Therru/Tehanu the dragon/child, who reached adulthood.

With Ged's wandering tendencies, readers tour the islands from Roke to the farthest shore where dragons fly and the dead walk. In this series, prepare to see dragons, creatures of the Old Powers, and plenty of feats of magic.

Â

The Hyborian Age of Conan

Robert E. Howard's creation, Conan the Barbarian, a.k.a. Conan the Cimmerian, lives on thanks to such writers as L. Sprague de Camp, Lin Carter, Robert Jordan, and Dale Rippke.

Conan lived in the Hyborian Age, supposedly after Atlantis sank but before other civilizations sprang into being. Kingdoms like Nemedia, Ophir, Zamora, Brythunia, Hyperborea, and Aquilonia sprawled across this mythical form of Earth. Hyperborea, from Greek mythology, was the original happiest kingdom on earth (way before Disney World)âa vacation spot for Apollo. Some believed that Hyperborea was Great Britain.

Having been a warrior, a thief, a mercenary, and a pirate, Conan later became king of Aquiloniaâthe most powerful kingdom. Not your average hero. When you read the exploits of Cohen the Barbarian in Interesting Times and The Last Hero, you can't help but see the parody.

The books spawned two Conan movies, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, one in 1982 and the other in 1984.

Â

Hogwarts and the London of Harry Potter

J. K. Rowling, the only author who outsells Terry Pratchett in Britain and possibly every other author in the world, created an instantly memorable character in Harry Potter and the other students and faculty of Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Although the stories take place in modern-day England, Rowling's world of wizards and witches is almost an alternate universe, where Muggles are not allowed.

The movies bring to life the Hogwarts of our imaginations with its gloomy edifice surrounded by rolling hills and eerie forest. Inside the castle, the ghosts, moving stairways, dark passages, and “live” pictures are all thereâas is the incredible danger Harry and his friends face.

Â

Star Trek's Worlds

The old television series, created by Gene Roddenberry in 1966, spawned other series and well over one hundred books. In the twenty-third century after a third world war, Captain James T. Kirk and his intrepid crew traveled from planet to planet “boldly going where no man has gone before.” The governing body for humans and aliens was the United Federation of Planets. (Kind of reminds you of the Republic, doesn't it?)

The first series was written by James Blish until his death. But many, many writers, including Margaret Armen, Larry Niven, Gordon Eklund, Walter Koenig, Michael Jan Friedman, and Diane Duane, contributed to the series. Then came other TV series and books: Star Trek: The Next Generation: Star Trek: Deep Space Nine; Star Trek: Voyager; and Star Trek: Enterprise.

Â

Midkemia/Kelewan

Raymond Feist's Riftwar Saga covered the wars with the Tsurani, an alien race of beings from Kelewan. Pug, one of the main characters

of the series, lived on Midkemia, a planet with three continents established by feudal societies, where dukes and princes lived peacefully or at war with elves, dark elves (moredhel), and dwarves. As with many fantasy lands, magic abounded. Oh, and there were dragons and dragonlords, too.

of the series, lived on Midkemia, a planet with three continents established by feudal societies, where dukes and princes lived peacefully or at war with elves, dark elves (moredhel), and dwarves. As with many fantasy lands, magic abounded. Oh, and there were dragons and dragonlords, too.

The Tsurani society had a Far East flavor while the Midkemians went the medieval Europe route. Other series followed such characters as Arutha and Pug beyond the Riftwar drama.

Â

The World of the Wheel of Time

Robert Jordan's massive Wheel of Time series might seem like The Lord of the Rings upon first glance with its Emond's Field, the Shire-like village from which Rand al'Thor and his friends (Mat, Egwene, Perrin) hailed. After all, we know we're in the midst of a society like something out of a Renaissance fair. The world opened much wider as Rand traveled with his friends and the Aes Sedaiâa female channeler or mageâand later went their separate ways (a breaking of the fellowship). With its Westlands, city states (Tar Valon), blighted areas, and seas, you feel as if you live there.

Terry Pratchett: Man of Mystery

Act I, Scene I:

In Which the Players

Are Discussed

In Which the Players

Are Discussed

Setting: Your home or wherever you happen to be now.

Â

Us:

Take a street-smart detective/cop/medieval monk/nosy British aristocrat/bounty hunter/little old lady well versed in psychology and an impossible case, and what do you have? A definitive work of mystery fiction by the likes of Terry Pratchett, P. D. James, Ed McBain, J. A. Jance, Lawrence Block, Janet Evanovich, Sue Grafton, Agatha Christie, Lilian Jackson Braun, Arthur Conan Doyle, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Wilkie Collins, Edgar Allan Poe, Ellis Peters, Dorothy Sayers, Sara Paretsky, Ross Macdonald, Ruth Rendell, Patricia Cornwell, Robert Parker, Ngaio Marsh, Ken Follett, Tony Hillerman, Margery Allingham, Georges Simenon, Donald Bain/Jessica Fletcher, and many others.

Take a street-smart detective/cop/medieval monk/nosy British aristocrat/bounty hunter/little old lady well versed in psychology and an impossible case, and what do you have? A definitive work of mystery fiction by the likes of Terry Pratchett, P. D. James, Ed McBain, J. A. Jance, Lawrence Block, Janet Evanovich, Sue Grafton, Agatha Christie, Lilian Jackson Braun, Arthur Conan Doyle, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, Wilkie Collins, Edgar Allan Poe, Ellis Peters, Dorothy Sayers, Sara Paretsky, Ross Macdonald, Ruth Rendell, Patricia Cornwell, Robert Parker, Ngaio Marsh, Ken Follett, Tony Hillerman, Margery Allingham, Georges Simenon, Donald Bain/Jessica Fletcher, and many others.

You:

Terry

Pratchett

?

Discworld

Terry Pratchett?

Terry

Pratchett

?

Discworld

Terry Pratchett?

Us:

Glad you asked.

Glad you asked.

You:

I really didn't. I'm just reading this.

I really didn't. I'm just reading this.

Us:

Since you asked, consider the mysteries solved by Commander Samuel Vimes and other members of the Watch.

Since you asked, consider the mysteries solved by Commander Samuel Vimes and other members of the Watch.

Every great work of mystery fiction needs at least two ingredients: (1) an intriguing mystery, many times involving a formidable adversary, and (2) someone to solve it. In a mystery subgenre such as police procedurals, a team of experts are put to the test. But many whodunit mysteries rest on the personality of the leading detectiveâamateur or professional.

The City Watch miniseries has many of the elements of mystery subgenres (classic whodunits, private-eye novels, cozies, police procedurals, suspense, thrillers) and defies them all.

30

For that reason, we'd dub Pratchett's main detectiveâSam Vimesâthe “Hardest-Working Crime Solver” in mystery fiction. Wondering why?

30

For that reason, we'd dub Pratchett's main detectiveâSam Vimesâthe “Hardest-Working Crime Solver” in mystery fiction. Wondering why?

You:

Not really, no. But I'm sure you'll tell me.

Not really, no. But I'm sure you'll tell me.

Us:

We will in the next scene. We have a lot of lines in that one.

We will in the next scene. We have a lot of lines in that one.

DISC-CLAIMER:

Plot spoilers ahead. Read at your own risk.

Act I, Scene II:

In Which Mystery

Subgenres Are Discussed

In Which Mystery

Subgenres Are Discussed

Us:

First, some handy definitions of mystery subgenres:

First, some handy definitions of mystery subgenres:

Â

Whodunits

Who took the countess's priceless diamond bracelet? Who killed the blackmailer? With mysteries like these, the main question, naturally, is “Whodunit?” The whodunit subgenre is the largest of the mystery subgenres. In books of this ilk, “great ingenuity may be exercised in narrating the events of the crime, usually a homicide, and of the subsequent investigation in such a manner as to conceal the identity of the criminal from the reader until the end of the book, when the method and culprit are revealed.”

31

This group includes “

cozies

”, “locked room” mysteries, and “aristocop”

32

mysteries. (For more on “aristocop” mysteries, see “

The Titled Crime Solvers: It's in the (Blue) Blood

”.)

31

This group includes “

cozies

”, “locked room” mysteries, and “aristocop”

32

mysteries. (For more on “aristocop” mysteries, see “

The Titled Crime Solvers: It's in the (Blue) Blood

”.)

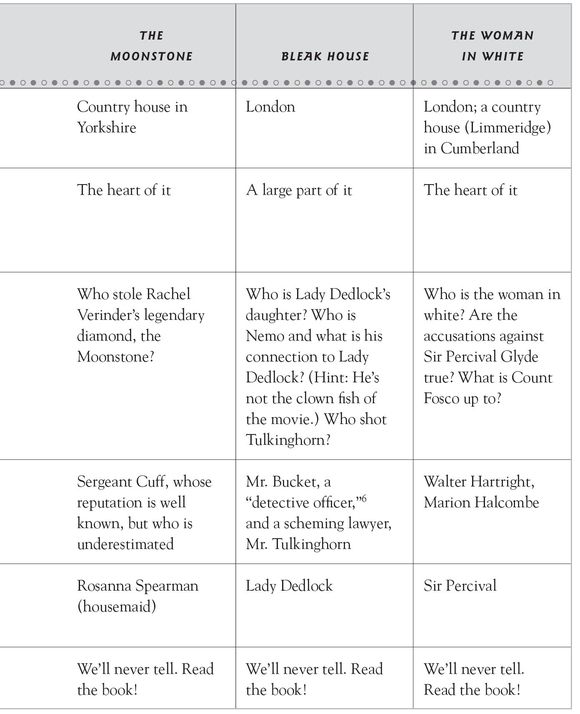

With classic whodunits such as

The Woman in White

and

The Moonstone

by Wilkie Collins, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” by Edgar Allan Poe (considered the first published detective story), or

Bleak House

by Charles Dickens, you might think of the well-crafted plots faster than the characters' names.

The Woman in White

and

The Moonstone

by Wilkie Collins, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” by Edgar Allan Poe (considered the first published detective story), or

Bleak House

by Charles Dickens, you might think of the well-crafted plots faster than the characters' names.

You:

Bleak House

is on DVD. Let's see, there's Esther Summerson, Lady Dedlock, Mr. Tulkinghorn, and there's â¦

Bleak House

is on DVD. Let's see, there's Esther Summerson, Lady Dedlock, Mr. Tulkinghorn, and there's â¦

Us

(

interrupting

)

:

The Sherlock Holmes novels, on the other hand, are classic whodunit detective novels. You might read them

because

of Sherlock Holmes, rather than the plot specifically. (For more about that, don't miss “Vimes versus Holmes: The Smackdown” in Act II, Scene I.)

(

interrupting

)

:

The Sherlock Holmes novels, on the other hand, are classic whodunit detective novels. You might read them

because

of Sherlock Holmes, rather than the plot specifically. (For more about that, don't miss “Vimes versus Holmes: The Smackdown” in Act II, Scene I.)

You:

My favorite Sherlock Holmes novel isâ

My favorite Sherlock Holmes novel isâ

Us:

Let's move on to private-eye novels. These are nonpolice detective novels. The characters are realistic rather than eccentric. These mysteries are populated by “old school” characters like Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, Nick and Nora Charles, Lew Archer, or the

Continental Op and “the next generation”: V. I. Warshawski, Matthew Scudder, Kinsey Millhone, Stephanie Plum, or the erudite Spenser (no revealed first name). (If you're confused about which author wrote which character, see the end of the chapter for a list.)

Let's move on to private-eye novels. These are nonpolice detective novels. The characters are realistic rather than eccentric. These mysteries are populated by “old school” characters like Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, Nick and Nora Charles, Lew Archer, or the

Continental Op and “the next generation”: V. I. Warshawski, Matthew Scudder, Kinsey Millhone, Stephanie Plum, or the erudite Spenser (no revealed first name). (If you're confused about which author wrote which character, see the end of the chapter for a list.)

This is where personality counts. Many private eyes in fiction have similar traits. They're tough (they have to be, to solve the grisly crimes in their beat), jaded, hard drinkers (or at least alcoholics on the mend), and have enough determination to stay with a case even after someone tries to run them over or push them out of a window. Most are good at what they do, or at least keep at a job until the truth is revealed.

Â

Cozies

.

According to an article written by mystery writer Stephen P. Rodgers,

33

a cozy mystery is “a mystery which includes a bloodless crime and contains very little violence, sex, or coarse language. By the end of the story, the criminal is punished and order is restored to the community.”

.

According to an article written by mystery writer Stephen P. Rodgers,

33

a cozy mystery is “a mystery which includes a bloodless crime and contains very little violence, sex, or coarse language. By the end of the story, the criminal is punished and order is restored to the community.”

With cozy mysteries, you might think of such characters as Hercule Poirot, Jane Marple, Lord Peter Wimsey, Jessica Fletcher, Jim Qwilleran/ Koko/Yum Yum. (You can't get much cozier than two cats.) Rather than ranked as strictly amateur sleuths, characters like Hercule Poirot and Lord Peter Wimsey are considered criminologists and are regularly consulted by the police. (And Poirot

is

a former cop.)

is

a former cop.)

Â

Police procedurals.

According to a definition posted at the Mystery Guide site, “police procedurals must be realistic depictions of official investigations. They emphasize teamwork, methodical pavement-pounding, lucky breaks, administrative hassles, and endless paperwork.”

34

According to a definition posted at the Mystery Guide site, “police procedurals must be realistic depictions of official investigations. They emphasize teamwork, methodical pavement-pounding, lucky breaks, administrative hassles, and endless paperwork.”

34

If you're a fan of such shows as

Prime Suspect, CSI,

or

Law and Order

(with all of its spin-offs)â

Prime Suspect, CSI,

or

Law and Order

(with all of its spin-offs)â

You:

What has this got to do with Terry Pratchett?

What has this got to do with Terry Pratchett?

Us

(

as if you hadn't spoken

)

:

âyou probably like your mysteries by the book, according to realistic police procedures. This is the form popularized in America by the late Ed McBain, Patricia Cornwell, Tony Hillerman, J. A. Jance, Joseph Wambaugh, and many others. But looking at the European police scene, you'll find such characters as Roderick Alleyn, Adam Dalgliesh, Endeavour Morse, the world-weary Jules Maigret, Reginald Wexford, and the forensics experts Brother Cadfael or Kay Scarpetta. These crime solvers walk a grisly beat.

(

as if you hadn't spoken

)

:

âyou probably like your mysteries by the book, according to realistic police procedures. This is the form popularized in America by the late Ed McBain, Patricia Cornwell, Tony Hillerman, J. A. Jance, Joseph Wambaugh, and many others. But looking at the European police scene, you'll find such characters as Roderick Alleyn, Adam Dalgliesh, Endeavour Morse, the world-weary Jules Maigret, Reginald Wexford, and the forensics experts Brother Cadfael or Kay Scarpetta. These crime solvers walk a grisly beat.

Â

Suspense.

Sometimes suspense and thrillers are lumped together. In suspense stories, the focus is on whether the villain will be caught before he or she strikes again. These are the edge-of-your-seat mysteries, many of which involve females as lead charactersâthe kind who can't help investigating even when the body count climbs. When you think of suspense, you might think of writers like Mary Higgins Clark (

Moonlight Becomes You

), Nancy Atherton (

Aunt Dimity Goes West

), or Anne Perry (

The Cater Street Hangman

). We would add Terry Pratchett to that list, even though Vimes has never shown his feminine side.

Sometimes suspense and thrillers are lumped together. In suspense stories, the focus is on whether the villain will be caught before he or she strikes again. These are the edge-of-your-seat mysteries, many of which involve females as lead charactersâthe kind who can't help investigating even when the body count climbs. When you think of suspense, you might think of writers like Mary Higgins Clark (

Moonlight Becomes You

), Nancy Atherton (

Aunt Dimity Goes West

), or Anne Perry (

The Cater Street Hangman

). We would add Terry Pratchett to that list, even though Vimes has never shown his feminine side.

You:

I see. I would've preferred a chart, though. Visual aids rule, you know.

I see. I would've preferred a chart, though. Visual aids rule, you know.

Us:

Moving on to the

thriller,

the focus is on fast-paced action where chase scenes and technology abound. The villains may be megalomaniacs bent on taking over the world or simply average joes gone postal. With thrillers, the main element is time. The clock is ticking to catch that kidnapper before the victim is killed or the bomb explodes. Writers like Tom Clancy, Ken Follett, and Elmore Leonard are well known in this subgenre.

Moving on to the

thriller,

the focus is on fast-paced action where chase scenes and technology abound. The villains may be megalomaniacs bent on taking over the world or simply average joes gone postal. With thrillers, the main element is time. The clock is ticking to catch that kidnapper before the victim is killed or the bomb explodes. Writers like Tom Clancy, Ken Follett, and Elmore Leonard are well known in this subgenre.

Act I, Scene III:

The Plot Thickens

The Plot Thickens

Whodunits

Us:

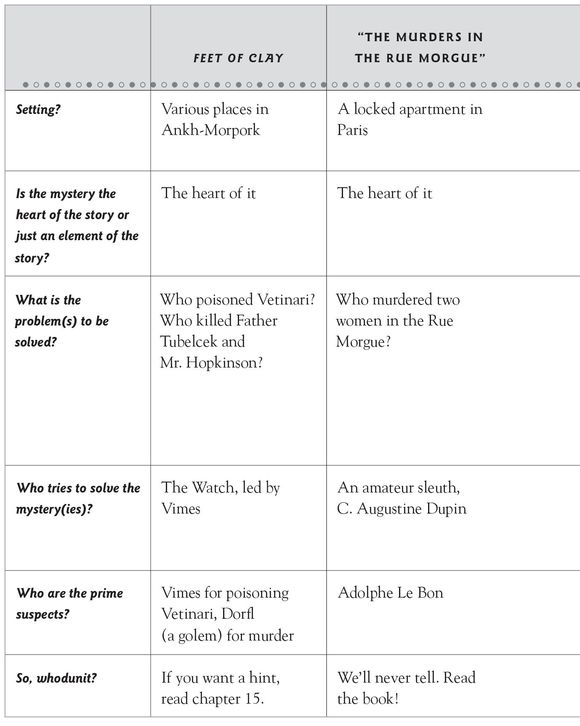

The Pratchett novels

Men at Arms

and

Feet of Clay

can be described as “who-or-what-dunits,” thanks to the fact that you never know what species (dragon, dwarf, werewolf, vampire, golem, troll, etc.) might have done the crime. Even so, both novels have the same “whodunit” elements as do classic works by Wilkie Collins, Charles Dickens, and Edgar Allan Poe. See for yourself as we compare

Feet of Clay

to Collins and Dickens's novels.

The Pratchett novels

Men at Arms

and

Feet of Clay

can be described as “who-or-what-dunits,” thanks to the fact that you never know what species (dragon, dwarf, werewolf, vampire, golem, troll, etc.) might have done the crime. Even so, both novels have the same “whodunit” elements as do classic works by Wilkie Collins, Charles Dickens, and Edgar Allan Poe. See for yourself as we compare

Feet of Clay

to Collins and Dickens's novels.

You

(

happily

)

:

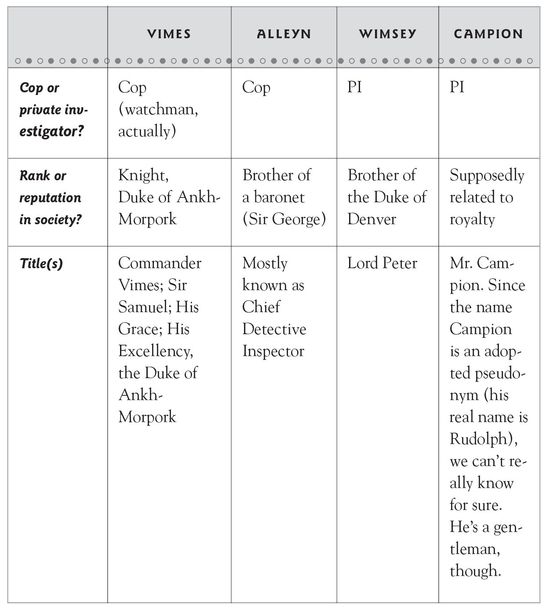

A chart! (

See charts on pages 36 and 37.

)

(

happily

)

:

A chart! (

See charts on pages 36 and 37.

)

Us:

The Fifth Elephant

also has a locked-room mystery element as Vimes investigates the theft of the famed Scone of Stone from a locked museum and a mysterious death that took place in a locked area.

The Fifth Elephant

also has a locked-room mystery element as Vimes investigates the theft of the famed Scone of Stone from a locked museum and a mysterious death that took place in a locked area.

Act II, Scene I:

Enter ⦠the Detective

Enter ⦠the Detective

Vimes versus Holmes: The Smackdown

Us:

Sherlock Holmes is unquestionably the most famous detective in fiction.

Sherlock Holmes is unquestionably the most famous detective in fiction.

You:

No question about that.

No question about that.

Us:

But Holmes is the kind of clue-analyzing detective who rubs a clue-hating cop like Vimes the wrong way. A discussion of methods might result in a

Smackdown

battle of Vimes and Holmes. We can't help but wonder who would win in a battle of the minds. Maybe it would go like this.

But Holmes is the kind of clue-analyzing detective who rubs a clue-hating cop like Vimes the wrong way. A discussion of methods might result in a

Smackdown

battle of Vimes and Holmes. We can't help but wonder who would win in a battle of the minds. Maybe it would go like this.

You:

Will Holmes and Vimes enter from stage left or stage right?

Us

(

brightly, because we always agree with you

)

:

Uh, thanks for sharing that. Take it away, Holmes and Vimes.

Will Holmes and Vimes enter from stage left or stage right?

Us

(

brightly, because we always agree with you

)

:

Uh, thanks for sharing that. Take it away, Holmes and Vimes.

Holmes:

“How often have I said ⦠that when you have eliminated

“How often have I said ⦠that when you have eliminated

the impossible, whatever remains,

however improbable

, must be the truth?”

35

however improbable

, must be the truth?”

35

Â

Â

Vimes:

“The real world was far too

real

to leave neat little hints. It was full of too many things. It wasn't by eliminating the impossible that you got at the truth, however improbable; it was by the much harder process of eliminating the possibilities.”

37

“The real world was far too

real

to leave neat little hints. It was full of too many things. It wasn't by eliminating the impossible that you got at the truth, however improbable; it was by the much harder process of eliminating the possibilities.”

37

Holmes:

“I have a lot of special knowledge which I apply to the problem, and which facilitates matters wonderfully. Those rules of deduction ⦠are invaluable to me in practical work. Observation with me is second nature.”

38

“I have a lot of special knowledge which I apply to the problem, and which facilitates matters wonderfully. Those rules of deduction ⦠are invaluable to me in practical work. Observation with me is second nature.”

38

Vimes:

“Every real copper knew you didn't go around looking for Clues so that you could find out Who Done It. No, you started out with a pretty good idea of Who Done It. That way, you knew what Clues to look for.”

39

“Every real copper knew you didn't go around looking for Clues so that you could find out Who Done It. No, you started out with a pretty good idea of Who Done It. That way, you knew what Clues to look for.”

39

Holmes:

“There is no branch of detective science which is so important and so much neglected as the art of tracing footsteps.”

40

Vimes:

“I never believed in that stuffâfootprints in the flower bed, tell tale buttons, stuff like that. People think that stuff's policing. It's not. Policing's luck and slog, most of the time.”

41

“There is no branch of detective science which is so important and so much neglected as the art of tracing footsteps.”

40

Vimes:

“I never believed in that stuffâfootprints in the flower bed, tell tale buttons, stuff like that. People think that stuff's policing. It's not. Policing's luck and slog, most of the time.”

41

Â

Pratchett and the Private Eye

Us:

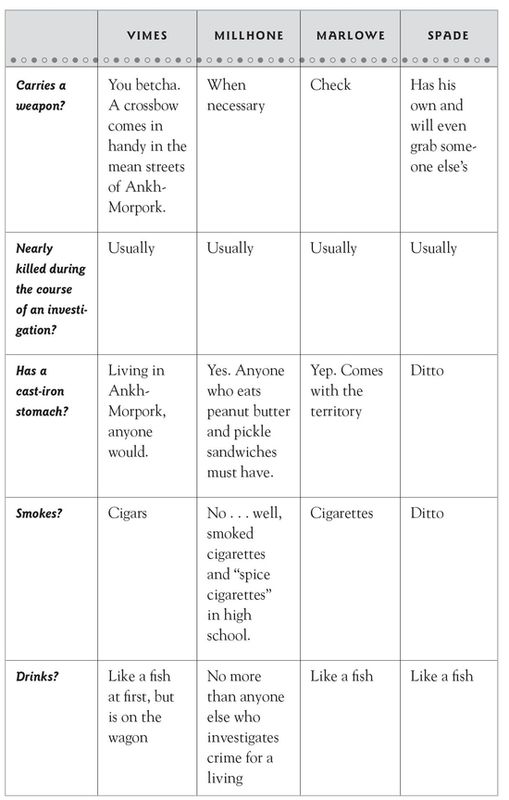

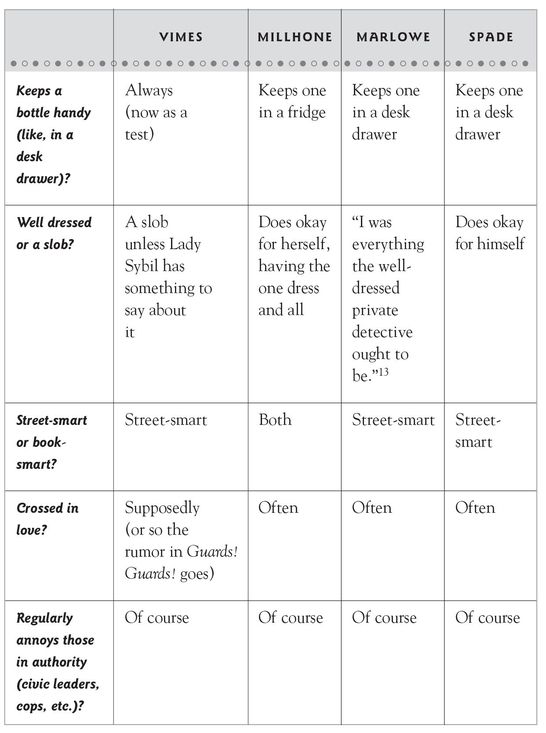

Although Vimes isn't a private investigator, he's asked to turn in his badge a number of times during the course of the series, which forces him to act like one. (See

Jingo

and

Guards! Guards!

) So, how does he fit in the hard-edged world populated by the likes of Kinsey Millhone, Philip Marlowe, and Sam Spade?

Although Vimes isn't a private investigator, he's asked to turn in his badge a number of times during the course of the series, which forces him to act like one. (See

Jingo

and

Guards! Guards!

) So, how does he fit in the hard-edged world populated by the likes of Kinsey Millhone, Philip Marlowe, and Sam Spade?

You:

Uh, you'll use another chart, perhaps?

Uh, you'll use another chart, perhaps?

Us:

Good idea!

(See chart

here

.)

Good idea!

(See chart

here

.)

Us:

Vimes may be hard-boiled like this lot, but he's also slightly cracked, thanks to living in Pratchett's world. Like Marlowe, he can be insubordinate, even though he can never one-up Vetinari, Ankh-Morpork's Patrician. Like Sam Spade, Sam Vimes is quick with an elbow when it comes to a fight. And, like Sam Spade, he fights dirty.

Vimes may be hard-boiled like this lot, but he's also slightly cracked, thanks to living in Pratchett's world. Like Marlowe, he can be insubordinate, even though he can never one-up Vetinari, Ankh-Morpork's Patrician. Like Sam Spade, Sam Vimes is quick with an elbow when it comes to a fight. And, like Sam Spade, he fights dirty.

Like all classic fiction private eyes, Vimes works cheapâmore than Carrot's $43 per month, plus allowances (the

Last Hero

rate). (Marlowe earns $25 dollars a day, plus expenses, and Archer gets $50 a day, plus expenses.)

Last Hero

rate). (Marlowe earns $25 dollars a day, plus expenses, and Archer gets $50 a day, plus expenses.)

Â

Murder with a Cozy Feel

Us:

Although many of Pratchett's mysteries take place within the teeming sprawl of Ankh-Morpork, some have a cozy element. So, while Pratchett might mention that a man has been beaten to death with a loaf of dwarf bread (and that's easy to believe if you know about the consistency of dwarf and other battle breads), you won't actually see the crime take place or see any (at least

much

) blood.

Although many of Pratchett's mysteries take place within the teeming sprawl of Ankh-Morpork, some have a cozy element. So, while Pratchett might mention that a man has been beaten to death with a loaf of dwarf bread (and that's easy to believe if you know about the consistency of dwarf and other battle breads), you won't actually see the crime take place or see any (at least

much

) blood.

You:

You mean like in

Saw IV

?

You mean like in

Saw IV

?

Us

(

as if you hadn't spoken

)

:

While Fletcher and Marple have the edge on coziness, Vimes at least is a contender.

(

as if you hadn't spoken

)

:

While Fletcher and Marple have the edge on coziness, Vimes at least is a contender.

Â

Us:

During a period known as the “Golden Age” of mysteries in Great Britain (between World War I and World War II), such writers as Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh, Margery Allingham, and Dorothy Sayers wrote their novels. They were the “queens” of English detective mysteries, the creators of the upper-class detectives Roderick Alleyn (Marsh), Albert Campion (Allingham), and Peter Wimsey (Sayers).

During a period known as the “Golden Age” of mysteries in Great Britain (between World War I and World War II), such writers as Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh, Margery Allingham, and Dorothy Sayers wrote their novels. They were the “queens” of English detective mysteries, the creators of the upper-class detectives Roderick Alleyn (Marsh), Albert Campion (Allingham), and Peter Wimsey (Sayers).

If they're the queens, Pratchett must be the joker.

You

(

shifts uneasily at your current location on Earth

)

:

No comment.

(

shifts uneasily at your current location on Earth

)

:

No comment.

Us:

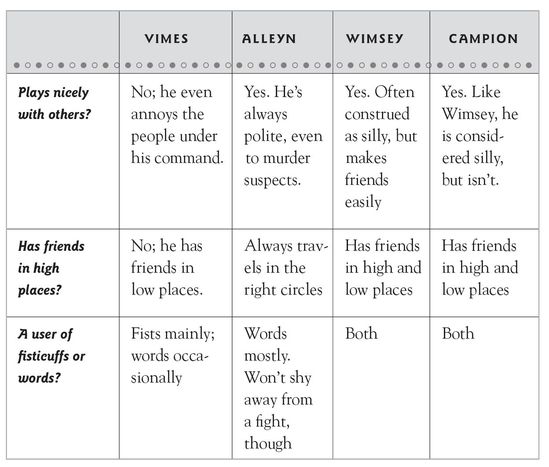

Pratchett plunks his square-peg character into the round hole of this gentlemen's league of suave, well-dressed, and well-educated detectivesâa description no one would dream of using for Vimes.

Pratchett plunks his square-peg character into the round hole of this gentlemen's league of suave, well-dressed, and well-educated detectivesâa description no one would dream of using for Vimes.

Here's how he measures up to the other members of the gentlemen's league.

Us:

Vimes would be the first to admit that, unlike his esteemed colleagues, he's no gentleman, nor the son of a gentleman. Thrust into society, thanks to his marriage to Lady Sybil and promotions for services rendered, Vimes is the thorn in everyone's side. Vimes's problem is that he can't stop annoying the upper crustâLords Selachii, Rust, and others, many of whom happen to be the assassins hired to kill him or Vetinari. If he encountered Alleyn, Wimsey, or Campion, Vimes might be tempted to stick him with a lobster fork rather than pass him one.

Vimes would be the first to admit that, unlike his esteemed colleagues, he's no gentleman, nor the son of a gentleman. Thrust into society, thanks to his marriage to Lady Sybil and promotions for services rendered, Vimes is the thorn in everyone's side. Vimes's problem is that he can't stop annoying the upper crustâLords Selachii, Rust, and others, many of whom happen to be the assassins hired to kill him or Vetinari. If he encountered Alleyn, Wimsey, or Campion, Vimes might be tempted to stick him with a lobster fork rather than pass him one.

Other books

Caledonia Fae 05 - Elder Druid by India Drummond

When Past & Present Collide: WP&PC by Sarah Hardy

Racing the Hunter's Moon (Entangled Bliss) by Sally Clements

The Bubble Reputation by Cathie Pelletier

Dawn of Night by Kemp, Paul S.

Havana Gold by Leonardo Padura

2000 - The Feng-Shui Junkie by Brian Gallagher

Dead Over Heels by Alison Kemper

Scorpions' Nest by M. J. Trow