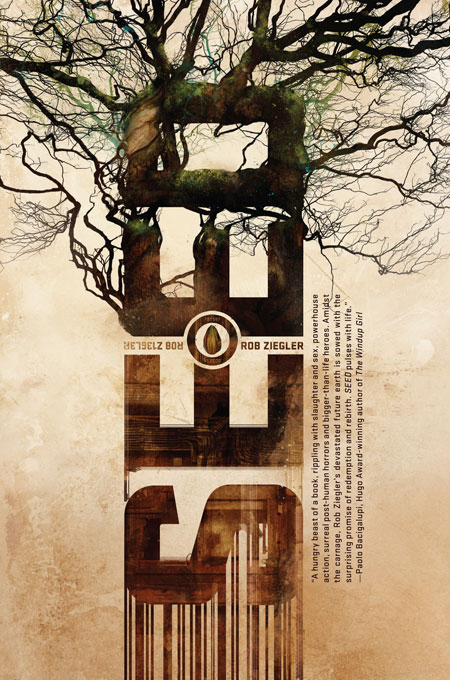

Seed

Authors: Rob Ziegler

SEED

ROB ZIEGLER

NIGHT SHADE BOOKS

SAN FRANCISCO

Seed

© 2011 by Rob Ziegler

This edition of

Seed

© 2011 by Night Shade Books

Cover art and design by Cody Tilson

Interior layout and design by Amy Popovich

Edited by Ross E. Lockhart

All rights reserved

First Edition

ISBN: 978-1-59780-323-6

E-ISBN: 978-1-59780-324-3

Night Shade Books

Please visit us on the web at

http://www.nightshadebooks.com

For Cindy

CHAPTER 1

he prairie saint wore a white lab coat with a black cross fire-branded onto the lapel, blotting out the name of some long dead doctor. He paced, pale and tall, between two burning fifty-gal drums. Spit flew from his lips as he sermonized, his stage the wrecked maw of a department store at the end of the abandoned shopping mall, his audience a captive huddle of migrants clad in paper FEMA refugee suits, sheltering from the sandblasting north Texas wind. Sweat gleamed on his forehead.

he prairie saint wore a white lab coat with a black cross fire-branded onto the lapel, blotting out the name of some long dead doctor. He paced, pale and tall, between two burning fifty-gal drums. Spit flew from his lips as he sermonized, his stage the wrecked maw of a department store at the end of the abandoned shopping mall, his audience a captive huddle of migrants clad in paper FEMA refugee suits, sheltering from the sandblasting north Texas wind. Sweat gleamed on his forehead.

He preached the end of days.

Brood yawned. He sat against the wall with Pollo and Hondo Loco, carving grit from beneath his fingernails with a sheet metal blade ground into the shape of a hook. The rhythms of the prairie saint’s grind lulled him. When he could no longer keep his eyes open, he tied black hair behind his head with a leather thong and settled deep into the oversized flak jacket he wore hidden beneath the broad spread of a canvas zarape.

Beside him, Pollo’d quietly bent bird-thin shoulders over a clamshell he held in one dirty palm. He seemed fixed on the sewing needle he held in his other hand. With intense concentration, he dipped the needle’s point into the tiny black pool of charcoal and water he’d mixed in the shell. Raised the needle, pressed it to sun-browned skin at the tip of his protruding sternum. The tiny glyph of a flightless desert bird slowly took shape there. One animal in a broad spiral that covered the boy’s ribs, shoulders, arms. Goners, he called them. Brood laid a hand lightly on the back of Pollo’s shaved head. Stubble upbraided his fingertips.

“

Hermano

,” Pollo murmured. He didn’t look up, didn’t break the meditative rhythm of his dip-and-pierce. He stared at an empty spot in front of him. Wind moaned against the building. The prairie saint ground on.

Brood let his eyes close. Found a happy half-waking dream already waiting: Rosa Lee was mere days away.

It had been hard work to make Rosa laugh. A speckle of acne on her cheeks made her shy, and she tried to be hard. Hard like her stone-faced Tewa brothers who spent their days watching the south road into Ojo Caliente, scoped rifles cradled in their arms. Likely to shoot anyone who came along and couldn’t show seed, and even some who could. But Rosa’s hair shone black as the charcoal in one of Hondo Loco’s water filters, and Brood hadn’t been able to let her alone. When he’d finally coaxed a laugh out of her it was as though he’d found a secret button in her belly, and every time he pressed it a bell would ring.

His mother had told him, when he was very young, not to fall in love until he was eighteen. The world was a hard place, she’d said, and love just made things harder. But Brood figured he’d never live to be eighteen, so he may as well be in love.

He held the memory of Rosa Lee deep in his chest, a second and secret heart, beating life into him. He could still hear the jingle of what seemed a thousand silver bracelets, fine as spider webs against her brown wrists as she’d taken him by the hand. Led him deep under the Ojo pueblo to a secret cave lit by biolumes. There in the thick sulfur stench of the hot spring got him drunk on myconal brewed from mushrooms. She’d pulled off her stained t-shirt and brought Brood to her breasts, cocooned him within the folds of her black, black hair. She’d smelled like the sweet figs that the Tewa grew in long plastic greenhouses lining the Ojo ridge top.

Brood inhaled deeply. Came awake to the smell of dust, acrid plastic smoke from the barrel fires, the sour shit stench of dysentery.

The prairie saint’s grind crescendoed. He paused, stared out at the migrants, waited. The silence stretched. The prairie saint glared. The migrants regarded him with hollow faces. The prairie saint’s three acolytes stepped forth from the department store’s shadow. Tall boys, thick faces, well fed. They each wore the red scarves over their heads and red-splashed paper FEMAs, signifying

La Chupacabra

. They stepped forward, glaring, until a few weary “amens” rose from the migrants. The prairie saint pulled his shoulders back, smiled approval, preached on.

“Amen,” Pollo echoed. He smiled but his eyes remained empty, fixed on his clam shell and needle.

Hondo Loco trembled with silent laughter beneath the greasy foil blanket he’d wrapped around bony shoulders. He pushed grey dreads out of his face and smiled black gums at Brood.

“Blessed are the meek,” he whispered, and laughter wheezed out of him. He settled back under his blanket, settled his chin against his chest, let dreads cover his face. A tired old man—he even pretended to snore a little.

One of the

Chupes

stepped forward, tossed a broken hunk of Styrofoam into a barrel fire. He stood over it for a moment, scanned the gathered migrants, then leered at a group huddled nearby.

Brood saw a girl there. A smear of dirt on her cheek, rats’ nests in her hair. She shuddered, obviously sick. Tendons protruded from her neck. The Tet, in full rigor. The

Chupe

boy motioned and his two companions stepped up. The girl turned her back, scooted closer into her group, a herd animal sheltering from predators. An older woman wrapped an arm around her. A young boy whispered something and the woman shushed him. The

Chupes

surrounded the group. One grabbed the girl’s hair.

“You got bad Tet, don’t you, baby bitch?” Brood heard him say. “You going north with us.”

The older woman stood. Soiled yellow FEMAs hung loose from her hungry frame as she faced the

Chupes

. The third

Chupe

gave her a kindly smile. Then drove his fist into her face. The old woman dropped. The sick girl cried out.

Anger flared in Brood. The girl had black hair. Black like Rosa Lee’s, black like Brood’s mother. He started to rise.

Hondo’s hand snaked out, gripped Brood’s forearm, hard as a hawk’s claw. The old man gave his head a tiny shake. As Brood watched, a blade flashed in the barrel fires’ sallow glow. A

Chupe

had his knife under the girl’s chin. He stood her up, marched her away from the crowd, sat her against the wall.

“You wait right here, girlie. You think about going anywhere, I cut up your momma.” He held up the blade for her to see. The girl sobbed, quivering like a snared rabbit. The other two

Chupes

laughed. The prairie saint preached on, never pausing.

Brood clenched his jaw, let out a breath, settled back against the wall. Hondo released his arm.

“Satori pays for Tet,

homito

,” he said. “

La Chupes

just getting themselves fed. Same as us.” He leveled one milky eye at Brood. “Same as us.”

“

Sí

.” Brood spit onto the cracked tile floor. “Don’t mean they ain’t bitches, every single one of them.” A slight smile crossed Hondo’s grizzled lips.

“

Sí

.”

The girl’s head fell between her knees and she shuddered, whether with sobs or Tet, Brood couldn’t tell. He eyed her for a moment, shook his head, and shut her from his mind.

He reached inside his zarape, shifted aside the ancient flak jacket and withdrew a hunk of smoked rabbit meat. Tore a piece off, nudged Pollo’s shoulder. Pollo snatched the meat without looking.

“Amen,” he said quietly.

“

De nada

.”

“Don’t be shy,” Hondo said. He extended his hand once more. Brood tore off a second hunk and placed it Hondo’s calloused palm. Hondo winked. “Amen.”

….

It had been a

Chupe

who’d turned them on to the prairie saint. They’d been rolling north on Hondo’s wagon, tailing a caravan up Route 83 a hundred or so miles north of old Laredo when they’d pulled into a hollowed-out gas station to siesta away the day’s heat. They’d found the

Chupe

there. A short whiteboy in splashed-red FEMAs, squatting on the remnants of a curb in the shade of a solitary cinderblock wall.

“

Que onda

,

guero

?” Brood called as Hondo pulled the wagon up short on the broken asphalt.

“Sorry, sir,” the whiteboy mumbled. “Don’t speak Spic.” Indecipherable swirls of tattoos covered his cheeks and forehead. Brood hopped down from the wagon.

“Crazy Tats. Where’d you get those tats, homes?”

The

Chupe

said nothing, just stared out at the empty distance where heat shimmers rose off the desert floor and the hollow west Texas wind whipped phantoms out of the dust.

“

Él está bendecido

.” Hondo tapped a finger against his temple. Brood shrugged. “What’s the matter, son?” Hondo asked the kid. The whiteboy blinked, then, and turned his eyes to Brood.

“Got anything to eat?”

“Your boys don’t take care of you?” Brood aimed a finger at the splash of red on the whiteboy’s paper FEMAs. The whiteboy stuck his tongue behind his lip and shook his head a little.

“Not so much.”

“We maybe got something to eat.” Brood smiled. “You anything to trade?”

“Maybe.”

“Satori?”

“What else? Got wheat.”

“Let’s see.”

The whiteboy hesitated. His eyes narrowed, fixed again on some distant patch of desert. Brood spread his hands wide.

“Don’t be scared, homie. S’all good.”

“All good,” Pollo echoed, distantly.

“You hungry, right?”

The whiteboy’s eyes refocused on Brood. He nodded, slid a bony hand inside the open top of his

Chupe

-stained FEMAs and withdrew a square of greasy cloth. Unfolded it, delicately proffered it. A dozen seeds lay there, thin as needles. Brood held his breath and leaned in real close, squinting. Knew instantly the seeds were wrong, too long, too frayed. Hope forced him to reach out anyway. He pinched a single seed between thumb and forefinger, brought it close to his nose, swallowed hard as he saw the tiny Satori barcode running its length. He closed his eyes, ran the barcode against his finger, searching for smooth perfection, genetic inherency.

Felt instead the lazed edge of a counterfeit.

He smiled again at the

Chupe

. Held the seed aloft on the tip of his index finger. It balanced there for a moment, trembling in the dry breeze as though mustering its courage, then sailed away into the Texas wastes.

“Hey!” the whiteboy cried.

“Fucking cheat grass.” Brood swatted the cloth away from the boy’s hand. Worthless seed drifted up, out, was gone. The whiteboy stood, watching it go. Violence rose in his face. Brood took a short step back—reached beneath his zarape, gripped the leather-wrapped handle of the hooked blade tucked in the waistband of his canvas pants.

The whiteboy hesitated, gradually seemed to chill, to assess the situation for the first time. He took them in, Brood standing before him, hand hidden beneath his zarape. Pollo, sitting cross-legged on a frayed Kevlar vest, scratching his canvas pant leg with a piece of charcoal. The whiteboy’s eyes lingered on the old carbon-mold Mossberg propped against the wagon’s water tank, within easy reach of where Hondo stood by the tiller. Hondo cocked a grey eyebrow, showed the boy friendly black gums.

“Well.” And now the whiteboy smiled, revealing a brown cavity the size of a pea in one front tooth. “Wouldn’t trade any Satori even if I had it.”

“First thing you said today,

ese

,” Brood told him, “makes me think you might be something other than stupid.”

“Ya’ll do look like capable gentlemen.” A swirl of tattoo wrinkled on the whiteboy’s cheek as his gaze grew speculative. “Could be I know something worth knowing. Sort of thing capable gentlemen might be able to do something with.”

“We’re capable,” Brood assured him.

Hondo snorted. “We something.”

“We’re capable,” Brood told the whiteboy. “Let’s hear it.”