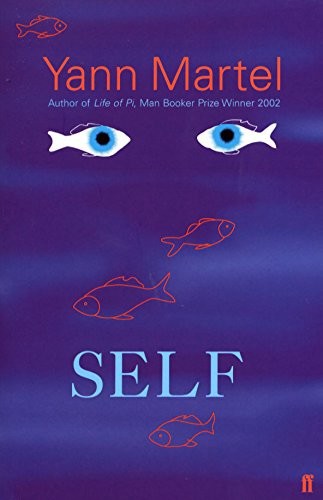

Self

Praise for

Self

“Superb … Masterfully written.… Martel has an almost otherworldly talent.… He is a powerful writer and storyteller, almost a force of nature.”

—

The Edmonton journal

“A brilliant, and very funny exploration of growing up, with Martel’s characteristic perceptiveness, eye for ironic detail and gift for phrase turning.… A fresh pair of eyes on the extramundane world around us.”

—

The Financial Post

“It is in the presentation of the story that [Martel’s] true genius lies. The way in which he positions the words on the page charges his language in a way that eludes even many of the finest Canadian novelists.”

—

The Vancouver Sun

“Yann Martel wonderfully represents the child’s universe as a seamless whole.… A penetrating, funny, original and absolutely delightful exploration.… [Martel] is a natural and often brilliant essayist and expositor, with a knack for aphorism and a rich cultural and literary foundation.”

—

The Globe and Mail

“Extraordinary.… Only rarely, in works by Martin Amis, Nicholson Baker or Kazuo Ishiguro, say, does one come across a character or narrator so perversely and entertainingly intelligent, witty and articulate. Martel ups his protagonist’s appeal with a life history that manages to be both imaginatively accessible and romantically exotic.… Martel’s narrator has some interesting things to say about the human condition … and he says those things eloquently and with disarming wit.”

—

NOW

“So vigorous and confident and sure-footed … so compelling, that Self’s education does end up being part of the reader’s. Like all good educations, it is hard to forget, once absorbed.”

—

The Toronto Star

“A narrative orchestrated by an outspoken ‘I’ that is candid, intelligent, likable, life-embracing, protean, chatty, smug, and mischievous … Martel is a bright, amiable, enthusiastic writer with an original, playful mind that he is not afraid to use.”

—

Quill & Quire

Also by Yann Martel

The Facts Behind the Helsinki Roccamatios

Life of Pi

VINTAGE CANADA EDITION, 1997

Copyright © 1996 Yann Martel

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Originally published in Canada by Vintage Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, in 1997. Originally published in hardcover in Canada by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, in 1996. Distributed by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Vintage Canada and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House of Canada Limited.

The Hungarian passage is from

Bluebeard’s Castle

by Béla Bartók.

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Martel, Yann,

Self

eISBN: 978-0-307-37563-6

I. Title.

PS8576.A765IS4 1997 C813’.54 C95-932906-4

PR9199.3.M37S4 1997

v3.1

Contents

| | | |

| Pour leur soutien durant la création de cette oeuvre, je tiens à remercier le Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec, pour la bourse; Valérie Feldman et Eric Théocharidès, pour leur hospitalité; et Alison Wearing, pour tout le reste . | | For their support during the writing of this novel, I would like to thank the Arts Award Section of the Canada Council, for the grant; Harvey Sachs, for laying before me the splendour of Tuscany; Rolf Meindl, for the computer help and the sofa to sleep on; and Alison Wearing , for everything else . |

| | | |

| à l’une, survivante | | to one who survived |

| à l’autre, disparue | | to another who didn’t |

CHAPTER ONE

I AWOKE

and my mother was there. Her hands descended upon me and she picked me up. It seems I was mildly constipated. She sat me on my potty on the dining-room table and set herself in front of me. She began to coo and urge me on, running her fingers up and down my back.

But I was not receptive. I distinctly remember finding the woman quite tiresome.

She stopped. She placed her elbows on the table and propped her head on her hands. A period of fertile silence ensued; I looked at her and she looked at me. My mood was in suspense. Anger was there, lurking. So was reconciliation. Humour was hovering. Sulking was seeping. It could go any way, nothing was decided.

Suddenly I stood up mightily, like the Colossus of Rhodes, I bent forward a little, and in one go I produced. My mother was delighted. She smiled and exclaimed:

| | | |

| “Gros caca!” | | “Big pooh!” |

I turned. What a sight! What a smell! It was a magnificent log of excrement, at first poorly formed, like conglomerate rock that hasn’t had time to set, and dark brown, nearly black, then resolving itself to a dense texture of a rich chestnut hue, with fascinating convolutions. It started deep in the potty, but

after a coil or two it rose up like a hypnotized cobra and came to rest against my calf, where I remember it very, very warm, my first memory of temperature. It ended in a perfect moist peak. I looked at my mother. She was still smiling. I was red in the face and sweaty from my efforts, and I was exultant. Pleasure given, pleasure had, I sensed. I wrapped my arms around her neck.

My other earliest memory is vague, no more than a distant feeling that I can sometimes seize, most often not. Being so dimly remembered, perhaps it came first.

I became aware of a voice inside my head. What is this, I wondered. Who are you, voice? When will you shut up? I remember a feeling of fright. It was only later that I realized that this voice was my own thinking, that this moment of anguish was my first inkling that I was a ceaseless monologue trapped within myself.

Later memories are clearer and more cohesive. For example, I remember a cataclysm in the garden. At the time I thought the sun and the moon were opposite elements, negations of each other. The moon was the sun turned off, like a light-bulb, the moon was the sun sleeping, the dimples on its surface the pores of a great eyelid, the moon was solar charcoal, the pale remains of a daily fire — whatever the case, one excluded the other. I was in the garden at a very late hour. It was summer and the sun was setting. I was watching it, blinking, squinting, burning my eyes, smiling, imagining the heat and the fire, the sizzling of entire neighbourhoods. Then I turned and there it was floating in the sky, grey and malevolent. I ran. My father was the first figure of authority I encountered. I

alerted him and dragged him out to the garden. But his adult mind didn’t grasp how this apparition threw my understanding of astrophysics topsy-turvy.

| | | |

| “C’est la lune. Et alors?” Je me cachais derrière lui pour me protéger de la radioactivité. “Viens, il est tard. Temps de faire dodo.” | | “It’s the moon. So what?” I was hiding behind him to protect myself from the radioactivity. “Come, it’s late. Time for bed.” |

He took my hand and pulled me indoors. I glanced a last time at the moon. My God, it was a free orb. It moved at random in the universe, like the sun. Surely one day they would clash!

My earliest aesthetic experience revolved around a small, clear plastic bottle of green-apple bubble-bath. To my parents a casually accepted free sample at the supermarket, it was to me a jewel that I discovered while my mother was giving me a bath. I was held in thrall by its endless greenness, its unctuous ooze, its divine smell. It left me dumb with pleasure.

When someone thoughtlessly made use of it a week later and I came upon my disembowelled treasure — I vividly recall the moment: my mother was wiping my bum and I was idly looking at the bathtub — I shrieked and threw the worst tantrum of my toddlerhood.

Other facts of my early life that are held to be important — that I was born in 1963, in Spain, of student parents — I heard only later, through hearsay. For me, memory starts in my own country, in its capital city, to be exact.

Beyond the normal overseeing of parenthood, neither my mother nor my father intruded unnecessarily into my world.

Whether my space was real or imaginary, the bathtub or the Aral Sea, my room or the Amazon jungle, they respected it. I can’t imagine having better parents. Sometimes I would turn and see them looking at me and in their gaze I could read total love and commitment, an unwavering devotion to my well-being and happiness. I would delight in this love. There was no cliff I couldn’t jump off, no sea I couldn’t dive into, no outer space I couldn’t hurtle through — where my parents’ net wouldn’t be there to catch me. They were at the central periphery of my life. They were my loving, authoritarian servants.

At the supermarket I would gambol about happy and carefree, playing with the cereal boxes, shaking the big bottles of mouthwash, looking at all the funny people — as long as I had my mother within sight. But if — the momentous if — if she skipped an aisle unexpectedly while I was still staring at the packaged meat, wondering what the cow looked like now — if she dashed for the fruits while I was still examining the jars of pickles — if, in other words, she became lost to me, that was a very different state of affairs. My body would tense, my stomach would feel light and fluttery. Tears would well up in my eyes. I would run about frantically, oblivious of everything and everyone, my whole being concentrated on the search for my mother. When I caught sight of her again, as, thankfully, I always did, the universe would instantly be re-established. Fear, that horrible boa constrictor of an emotion, would vanish without a trace. I would feel a hot burst of love, adoration, worship, tenderness, for my sweet mother, with somewhere in there a brief roar of intense hatred for this brush with oblivion she had put me through. My mother, of course, was never aware of the existential fluctuations, the

Sturm und Drang

, within her small fry. She sailed through the supermarket serenely indifferent to

my exact location, secure in the knowledge that she’d find me right next to her by the time she got to the check-out. That’s where the chocolate bars were.

I cannot recall noticing, as a small child, any difference between my parents that I could ascribe to sex. Though I knew they weren’t the same thing twice over, the distinctions did not express themselves in fixed roles. I received affection from both of them, and punishment too, when it came to that. In the early years in Ottawa it was my father who worked outside the home, at the Department of External Affairs, which had an awesome ring to my ears, but my mother was working at home on her Master’s thesis in linguistics and philosophy. What my father did during his daylight hours at External was unknown to me, and therefore remote. My mother, on the other hand, wrestled daily with stacks of thick books, in Spanish yet, and she produced endless reams of paper covered with her precise handwriting. I was a witness to her labour. Her thesis was on the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset. She fetched a hammer once and held it in front of me and told me that the nature of a hammer, its

being

(her word), was defined by its function. That is, a hammer is a hammer because it hammers. This was one of Ortega y Gasset’s key insights, she told me, fundamental to his philosophy, and Heidegger had filched it. Pretty obvious to me, I thought, I could have told you that, I thought, but I was nonetheless duly impressed. My mother was clearly involved in deep and difficult matters. I took the hammer and went outside and bashed dents into the edge of our driveway, reinforcing the hammer’s identity.