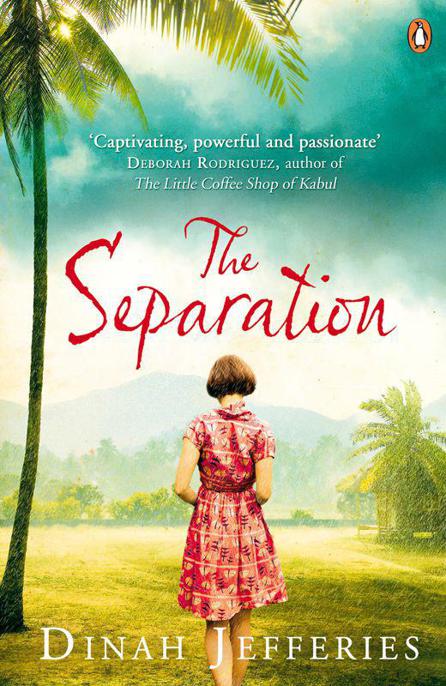

Separation, The

Authors: Dinah Jefferies

Dinah JefferiesTHE SEPARATION

PENGUIN BOOKS

Dinah Jefferies was born in Malaya in 1948 and moved to England at the age of nine. She has worked in education, once lived in a ‘rock ’n’ roll’ commune and, more recently, has been an exhibiting artist. For a while she was an au pair in Italy, and also spent five years in northern Andalucía, where she began to write. She spends her days writing, with time off to make tiaras and dinosaurs with her grandchildren.

The Separation

is her first book.

For my mother and my daughter

The man smoothed down the lion’s paws with a sponge he’d dipped in a bucket of water, then withdrew a knife from a leather pouch at his waist. He glanced up at the waiting crowd, before bending his head and carefully sharpening the creature’s claws.

The young girl, squatting a foot away, reached out to touch the lion’s mane with her fingertips.

‘No!’ the man shouted, as he pushed the child away. ‘Not yet.’

Her head hung for a moment, but then she glanced back over her shoulder, smiled shyly at the woman who stood watching, and swivelled back to keep her eyes on the creature.

A gust of wind lifted a layer of sand and sent a thousand grains dancing and whirling. The man reacted quickly, dampening down the surface of the beast before more could be whisked away.

The watching woman shivered. Her red-gold hair was cut close to her head, with a Marcel wave to keep it neat, and she wore a pale blue dress with darker blue cornflowers at the modest hemline, with only a thin white cotton cardigan to protect her from the sudden chill.

Once he had satisfied himself that the animal was complete, the sculptor bowed, then walked round the crowd, an upturned hat in his hand. The woman listened to the chink of coins and dipped into her purse.

The sound of horses’ hooves rang on the cobbled road behind

the esplanade, but it was not they who drew the woman’s attention. Her eyes remained fixed on the little girl, now kneeling on the sand, and gathering handfuls that glistened silvery-gold in the pale sunlight.

As the milling crowd dispersed, instead of their murmurs, or the noise of screaming seagulls and the waves of the ocean, the tap of hammer on metal filled the air. The woman glanced back at what had once been the grand pier, its elegant wrought ironwork bent out of shape by fire. She caught the scent of cockles in vinegar.

‘Are you hungry?’ she asked the child.

The little girl shook her head. There was hesitance, an uncertainty that revealed itself in the child’s slight blush.

‘What about a liquorice stick?’

The woman knelt down beside the child and drew close. Close enough to smell the sweetness of her hair. She took a long slow breath, and exhaled through lips that trembled only slightly. She stood, shook sand from the hem of her floral skirt, and took hold of the girl’s hand.

‘Let’s run, shall we?’

A look passed between them and they raced along the beach, kicking up sand and shells and stumbling and slipping until they reached the waiting nun.

At heart the nun was not unfeeling, and with a kindly look she touched the woman’s shoulder. Just a fleeting touch that ensured the exchange would be smooth, tears kept at bay, and emotion restrained. The child tipped back her head and turned her hazel eyes on the two women, then beyond them to where red and blue flags lined the sandy sweep of the bay.

For the woman, the day had begun with excitement and a sense of elation. Now it was almost over, she could not take her eyes from the child’s sharp-angled, stick-thin body. She patted the little girl’s auburn hair and fixed the moment in her memory.

But it would be different for the child. As

her

memory receded and blended into the past, she would doubt: wonder if the day,

the lion, and the woman existed only in her mind. She would seek to capture details of a time that could not be recovered. There would be resonance – a dress, a smile. Only that. And the woman would continue to stifle her sorrow.

‘Come along,’ the nun said, and took the child’s hand. ‘We need to get on that tram, or we won’t reach the railway station in time.’

The woman in the blue dress stepped away, then glanced back to look at the golden sand lion, aware the incoming tide would soon wash it away.

1

They couldn’t see me beneath the house on stilts. But I spied on them. Our amah, and Fleur, my little sister. I heard sandals on the patio – flip-flop, flip-flop – and Fleur’s sobs as she ran. Then the swish of her old pink rabbit, dragged by its ears over the pebbled path.

Amah’s shrill Chinese voice came after. ‘You come here now, Missy. You spoil rabbit. Carry him like that.’

‘I don’t care! I don’t want to go,’ Fleur shouted back. ‘I like it here.’

‘Me too,’ I whispered, and sniffed a mix of dead lizards and daddy-long-legs. I didn’t mind them.

Beyond my earthy hideout, past the end of the garden, was the long grass, where nobody dared go. But I wasn’t scared of that either.

What I

was

scared of was leaving.

Later on, when the sky turned lavender, Daddy pointed out across the same view. Now, from an upstairs balcony, a Tiger beer in his hand, he looked past the lawns and over the hills. To England.

‘It’s never warm enough there in January,’ he said, talking to himself and rubbing his jaw. ‘With a raw wind that makes your cheekbones ache. Not like here. Nothing like here.’

‘Daddy?’

I watched his bony face, the large Adam’s apple and straight line of his mouth above. He swallowed, the apple rose and fell, and his eyes came back to me and Fleur, as if he’d just remembered us. He sort of smiled and gave us both a squeeze.

‘Come on, you two. No need to look so miserable. We’ll have a great life in England. You like swinging from trees, don’t you, Em?’

I nodded. ‘Well, yes, but –’

‘What about you, Fleur?’ he broke in. ‘Plenty of streams to paddle in.’

Fleur’s mouth remained turned down. I caught her eye and pulled a face; it sounded too much like the jungle to me.

‘Come on,’ Dad said. ‘You’re a big girl now, Emma. Nearly twelve. Set an example to your sister.’

‘But, Daddy,’ I tried to tell him.

He went to the door. ‘Emma, it’s settled. Sort out the books you want to take. That’ll keep you busy. Just a few, mind. Come along, Fleur.’

‘But, Dad.’

When he saw my tears, he paused. ‘You’ll love it, if that’s what’s bothering you. I promise.’

I felt very hot, and the thought of my mother made me catch my breath.

He opened the door.

‘But, Dad,’ I called after him, as he and Fleur went out. ‘Aren’t we going to wait for Mummy?’