September (17 page)

Authors: Gabrielle Lord

Kelvin muttered something.

‘Cyril?’ Oriana called out the door of the study.

Next thing I knew, I was being dragged down the stairs by Kelvin and Sumo and out the back of the house where another car, a light grey sedan, was parked beside Oriana’s dark blue Mercedes. Sumo opened the boot of the grey car, picked me up with one hand, and shoved me into it. The lid slammed shut and I was thrown into darkness with a sick sense of déjà vu.

‘Let me out of here!’ I screamed and thrashed. ‘You can’t do this!’

‘What are you going to do, buster? Call the cops?’ hissed Sumo’s voice.

I lurched sideways in the darkness of the boot as the car started, swung around and took off.

This was the end of the line for me. Dingo Bones Valley was way out in the desert. It was notorious. People said that it got so hot out there, that birds dropped dead out of the

sky. It was the sort of area where people were found dead lying near their cars, because they’d broken down and run out of water. Or they’d be found, kilometres away, dead on the track, where they’d collapsed in their useless search for water. Sometimes it was weeks before another car came by. I would never be found. Maybe in years to come, someone—a prospector—might stumble upon my rotted corpse.

In the suffocating heat of the boot, I bumped along, my arms and legs aching from the

unnatural

position that I was tied in. I blinked in and out of consciousness—barely able to breathe.

Long hours passed and I started to get cold. As hot as the desert was during the day, it was just as dangerously cold at night. Although the boot ride was horrible, I was begging for it not to end. I didn’t want to have to face what was going to greet me outside once we stopped. But, inevitably, the car stopped.

I tried to think, to plan a possible escape. But what could I do? Without the use of my hands and legs, escape was impossible.

A sudden rush of cold air hit me as the boot was opened. Kelvin loomed over me but I couldn’t see his expression in the darkness.

‘Just leave me here, Kelvin,’ I begged, as he hauled me out. He was alone. ‘Please. You don’t have to kill me. She’ll never know.’

His silence was frightening as he threw me on the rough ground. I was barely aware of my surroundings. Ahead of me, I thought I could see a ridge, and above it the starry night sky.

‘Just get in the car and drive away,’ I said. ‘You’ve done what she told you to do. You don’t want my death on your conscience, do you? Kelvin, don’t you remember? I saved you when those guys were beating you up outside the casino that night. You can’t kill me.’

‘I don’t owe you anything,’ Kelvin muttered.

‘I’m not saying you do. But Kelvin, she’s a horrible woman. She killed your cat? Why do you keep carrying out her dirty work? I heard the way she talks to you. You deserve better than that, Kelvin.’

He gave me an intense look but said nothing. The night air was cold, but sweat was dripping down his brow like he’d just run a marathon.

‘Surely you’d like to be free of her,’ I said. ‘Work for someone who has some respect for you?’

‘I know something that she doesn’t know I know, and I could—’ he started to say.

‘What?’ I asked, stalling for time. ‘What do you know about her? What could you do?’

‘Shut up!’ he demanded, his voice hardening again. Something like fire blazed across his eyes. He reached into the car and pulled out a gun.

‘Don’t do it!’ I pleaded.

‘I told you to shut up!’ he said, aiming the gun at my head. ‘Can’t you get that through your thick skull?’

I knelt on the ground with the desert sounds rustling around me, and waited for the end. I said goodbye to my mum and Gabbi, and Boges and Winter.

The sound of the shot rang out.

Blazing heat. Pain. Aching wrists and legs. Thirst. Thirst.

Slowly, I tried to open my eyes. They seemed to be stuck together. I could barely swallow, my mouth was so dry. I was lying face down in the red dust of Dingo Bones Valley. But I was alive.

I spat red dust out of my mouth and rolled over. The blazing sun beat down on me. I tried to sit up and rolled over onto my belly again, away from the light. My eyes ached. They were dry and filled with grit. Scared at what I might find, I slowly put my hand to the right side of my head, where the shot had deafened me. I felt around gently. But there were no wounds, no blood. Then I noticed, in the red dust, a long straight track made by something small and moving

fantastically

fast. Was that the bullet track?

The shot must have been deflected in some way. Because I seemed to be OK. OK, considering I’d been dumped in the middle of Dingo Bones

Valley

, tied hand and foot.

What? My hands and feet were free! I crawled to my feet and saw the ropes lying beside

me-they

looked like they’d been cut through with a knife.

Somebody had freed me. But who? Kelvin?

I looked around in the shrill, desert air. Not a soul in sight. No living thing at all. Just the red dust stretching out in every direction, broken here and there by clumps of dried, white grass.

Without food and water, I was as good as dead. I looked around for shelter, but there was nothing. No shade,

nothing

. I lay back, defeated.

As I squinted towards the sky, I saw two eagles circling. Were they waiting for me to become weak enough for their attack? I could die lying down, or I could die on my feet, trying to find my way out. The choice was mine.

I climbed to my feet and started walking.

I realised that there was, in fact, a road. But it was almost impossible to see, because the road looked much the same as everywhere else—red

and dusty. I knew that if I was ever going to be found, or if I was ever going to find anyone, I had better stick to this road.

Every slow footstep was painful, every breath scraped through my dry throat. My tongue felt like an old boot and my lips were cracked and parched, splitting painfully at the edges. I pulled my hoodie over my face in an effort to keep out the scorching sun.

I’d been walking for hours. My mouth was getting drier and drier, but I forced myself to keep moving.

The landscape never changed. It was

nothing

but endless red dust, millions of microscopic crystals twinkling under the searing sun, with the occasional tuft of bleached grass. From time to time, I saw bones. Nothing lived here except the eagles and the crows. Even the dingoes had more sense to go elsewhere.

My feet were swelling up and I could feel

blisters

on the back of my heels.

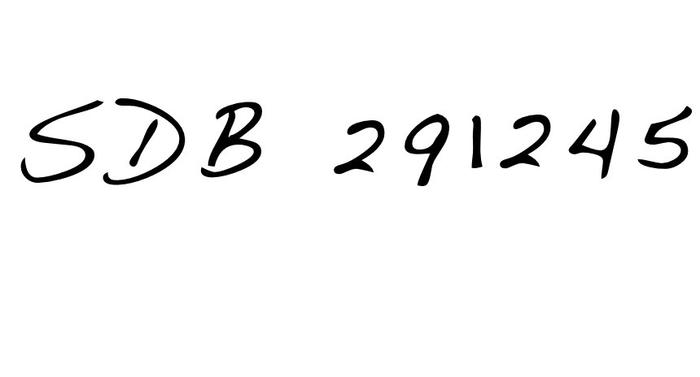

My socks were slipping. I sat down and undid my sneakers, pulling them off. As I removed the sock from my left foot, I leaned forward, puzzled. There was something black on my ankle. I tried to focus my dry, bleary eyes. There was

something

written there.

Letters? Numbers? I couldn’t focus my eyes.

What? Did Oriana de la Force catalogue and number all her victims like this? Who had

written

this on me? It looked like black ink. I looked at my sock. There was nothing on that except red dust. Nothing had rubbed off. I didn’t have enough spit to try wetting it. But it seemed that someone had written these letters and numbers in permanent ink on my skin.

I pulled my socks and shoes back on and kept going.

Before long I heard some kind of noise. At first I thought it was just the roaring in my head. My heart was pumping hard and I imagined my blood turning into toffee as I dehydrated. How long could I go on like this? But the sound persisted. I stopped my dragging footsteps and listened.

It was the sound of an engine! I stared into the west, trying to make out something in the distance, blinded by the sun glaring straight into my eyes.

It was the sound of a car! In the distance I could see a puff of red dust near the horizon. It was a vehicle, and it was coming my way!

I staggered out into its path, waving my arms like a madman.

‘Hey! Stop! Over here! Stop!’ These were the words I tried to say, but they sounded more like the squawking of a crow.

I tore off my hoodie and tried to wave it.

The vehicle approached me in a cloud of dust.

It was an old ute with a canvas water bag hanging off the bumper bar. I couldn’t take my eyes off the water bag. As it approached, I limped and staggered towards it, waving my dusty hands. I hoped I wouldn’t frighten

whoever

was driving. The truck slowed and finally stopped a few metres away from me. I lurched and stumbled closer.

‘Water,’ I croaked. ‘I need water.’

Slowly, the passenger door opened. I tried to look through the dusty windscreen, but could barely see into the interior of the cabin, although I could make out the head and shoulders of the driver.

I walked around to the passenger side door and peered in. A dusty, wizened man was staring back at me, a battered hat pulled over his

sunburnt

features, his hands like claws on the steering wheel.

‘There’s a bottle of water there, sonny,’ he said. ‘Hop in and help yourself.’

I didn’t need a second invitation. I hauled myself into the filthy cabin of the ute, kicking rubbish away, until I finally fell back exhausted on the seat, grabbing the bottle of water that the driver indicated. I ripped the top off and emptied a litre of water into me in about two seconds flat.

‘You sure was thirsty, sonny,’ cackled the driver, revealing yellow, broken teeth. But to me, just then, the old guy was about the most

beautiful

thing in the world. ‘You here on holiday?’

I looked at him. Was he serious? Who’d come to this barren desert for a holiday?

He threw his head back in a screech of laughter.

‘If you want more water, there’s a water bag hanging off the front of the vehicle.’

‘I need to make a phone call,’ I said.

Miraculously

I still had my phone on me, but it had no signal whatsoever. Plus the battery was about to die.

‘Where are you heading?’ The driver asked as the truck lurched off again.

‘To wherever you’re going,’ I said. ‘Somewhere I can get a feed and maybe a place to rest. After I’ve called my friends in the city.’

‘The name’s Stanley. But everyone calls me Snake.’

‘Tom,’ I said.

‘I’ve been prospecting,’ said Snake, ‘looking for sapphires. There used to be gold but now there’s no water to wash it in anyway so we go after sapphires instead, my partner and me. What’s that tattoo on your ankle mean?’

He didn’t miss much, I thought, noticing that my sock had slipped down.

‘Just some numbers I want to remember,’ I said.

‘A phone number? In case you get lost?’ The old prospector asked before cackling with laughter.

I squirmed uncomfortably in my seat. I was so relieved that I’d been picked up, but this guy’s laugh had a nasty edge to it.

‘You’re very lucky I came along when I did,’ he said, as if reading my thoughts. ‘Lucky for me, too. Otherwise, you’d have gone to waste out there.’

I flashed a look at him. That was an odd thing to say.

‘True,’ I agreed. ‘No-one could survive out there for very long.’

‘Now, ain’t that the truth,’ said the old

prospector

, showing his yellow teeth again as he grinned. ‘We were looking for Lasseter’s Reef when we first came out here. Me and my partner. That was years ago.’

I wondered if Winter had escaped with the leather handbag OK, and whether the

fingerprint

had held up. I was impatient to call them. ‘When will we be there?’ I asked. ‘Wherever we’re going?’

‘Not far to go, now. In fact, if you look straight ahead you’ll see the township.’

Sure enough, down the track, I could see the roofs and trees of the township. Soon I’d be able to hook up with my friends again. Oriana de la Force hadn’t won this round.

As the old car rattled down the main street, I looked around, puzzled. Where was everybody? Maybe it was the shocking heat keeping

everybody

indoors. But when I looked at the shops that lined the dusty street, they seemed to be boarded up. After the shops, there was a

scattering

of houses but they too seemed deserted, with broken windows and vines growing out of the chimneys.

‘Is this some sort of ghost town?’ I asked

Snake, who was hunched over the wheel, trying to avoid the worst of the potholes in the road.

‘Not quite,’ he said. ‘My partner runs the general store.’

I felt a lot of relief at the mention of a general store. I could use the phone, buy something to eat and maybe even find a lift or a bus to get me back to civilisation.

The prospector was parking the truck when I noticed that the scattering of vehicles parked in the street were really old and looked like they’d been abandoned too.

We hopped out of the cabin.

Snake looked at me and must have seen the confusion on my face. ‘The gold ran out years ago. The bank closed, the medical clinic closed, the shops started closing because nobody bought anything anymore, even the pub closed. The young folk all left town because there weren’t any jobs. And then, after a while, there were just a handful of old people living here.’ He put his hands on his hips and cackled his unpleasant laugh again. ‘Then they went, too. So now it’s just me and Jackson at the general store.’

The store had some timber steps leading up to a dusty verandah, and a couple of dirty windows stacked with bleached-out displays of

groceries

and hardware. I followed Snake through the

flyscreen door. A little bell jingled as we entered, and a dog barked.

‘Jacko? You here? We’ve got a visitor.’

All the stock looked tired and old: stacked up tinned food with rust spots on the top and

peeling

labels. Everything was covered in grease, grime and dust. I doubted anyone had bought anything in this general store for a long time, thinking the expiry dates must have been dated ten years ago, at least. On the wall behind the counter was a map of the area, curling round the edges and spotted with fly dirt.

I heard the sound of shuffling feet. ‘Who’s there?’ a voice called.

‘Who do you think it is? It’s me, Snake. I have a young traveller with me.’ Snake prodded me sharply in the back.

Jacko stepped out of the shadows. He was a gaunt, bearded man with sharp eyes hidden under bushy eyebrows. At his side stood a huge black dog.

‘He looks OK,’ grunted Jacko. ‘It’s a long time since we’ve had a visitor. Meet Sniffer here. The best nose in the country, ain’t you, Sniffer? He can track anyone, any time, through any country.’

The dog growled and stared with his brown eyes as the two old geezers chuckled. I looked from one to the other, unsure.

‘Is there a public phone in here?’ I asked.

‘Of course there is,’ said Snake, smirking. ‘Over there.’ He pointed to an old-fashioned red phone sitting on a shelf. I stepped over to it

hesitantly

and picked up the handset.

The line was dead. The handset wasn’t even connected to the telephone—it had been cut.

‘Vandals,’ said Jacko, shaking his bearded head.

‘They used to be shocking round here,’ Snake added. ‘But it’s pretty good now, isn’t it, mate?’

Jacko nodded. ‘Pretty good,’ he repeated.

‘So what about the phone?’ I asked. ‘Do either of you have a phone I could please use?’

‘You could,’ Jacko replied, pulling a mobile phone out of his pocket.

‘I’d pay you for the cost of the call,’ I offered.

‘It would cost you a lot,’ Jacko said, gripping the mobile in his leathery hand.

The mean old storekeeper held the power. I wasn’t in the mood for games. Not after

everything

I’d been through.

‘Whatever it costs,’ I said. ‘I have to make a call.’

Jacko looked at Snake and they both laughed.

‘OK, then,’ said Jacko. ‘Do you have any idea how much a telecommunications tower costs?’

I looked at him, confused. He switched on the phone and handed it to me. ‘No signal,’ I read. I waved it around but nothing changed.

‘You mean this is a dead spot?’

The pair laughed disturbingly again. ‘You got it, boy!’ said Snake. ‘You got it in one.’

Here I was, stuck in the middle of nowhere, with two complete weirdos. What in the world was I going to do?

The big black dog shook his head, making the metal tags on his collar jingle.

‘Is there anywhere else I can go to make a call?’

The pair stared at me blankly.

‘But I have to get back to the city! There are things I have to do! Is there a bus? Do either of you ever drive to the city?’

‘Sure,’ said Snake. ‘I went to the city in …’96. Or was it ’97? Do you remember Jacko?’

‘What about public transport?’ I asked, increasingly frustrated with every word they spoke.

I was aware that both men were looking at each other strangely. Something was

happening

between them that I didn’t understand. Like they were communicating without words. Then Jacko spoke.

‘Sure,’ he said. ‘There’s that bus that comes through in the morning, isn’t there, Snake?’

‘That’s right. Nice, solid bus in the morning. Only about a fifteen or twenty minute walk from here to the highway. Have you back in the city in seven or eight hours.’

Who were these people and what kind of general store were they running? It was obvious no customers had been here for years.

Everything

was festooned with cobwebs and the dust on the floor showed no footprints but our own. I wanted to get out. But I knew I had to make it to the highway and wait for the bus.

I moved closer to the map, studying it, analysing the scale. It showed Dingo Bones Valley township and a number of other small townships connected by a single road. That must have been the road the bus would take.

I started walking out of the store. Snake called after me. ‘Where are you going?’

‘To the highway,’ I said.

‘Are you crazy? Nobody walks around in the middle of the day here. You don’t have any water or any food, and the bus ain’t coming till

tomorrow

. You’d be crazy to go now.’

‘And look at yer,’ said Jacko. ‘Ain’t you a sight for sore eyes! You’d be much better off resting for a while then setting off in the cool of the early morning.’

I looked down at my feet, imagining the

multitude of blisters I’d gained. I was exhausted, hungry and still thirsty. They were right.

‘There’s the boarding house across the road,’ said Snake. ‘That’s where I camp. There are plenty of rooms. Check it out and take your pick. Tell you what. I’ll even share my beans with you.’

‘Here,’ said Jacko, throwing a tin of beans to his mate. ‘My shout. And here,’ he added,

throwing

me a water canister. ‘You’ll need that.’

I turned to go, aware of their eyes on my back. I heard the dog’s claws clicking on the dusty floorboards. He followed me out to the verandah.

‘Good dog,’ I said to him nervously. I was relieved he sat down while I walked away.