Sergeant Gander (11 page)

Jeremy Swanson, who spent over five years researching and documenting Gander's story, was equally pleased, stating, “I feel absolutely overjoyed seeing the joy in the faces of those veterans. For me, it marks the successful end of a project that created a new Canadian hero.”

10

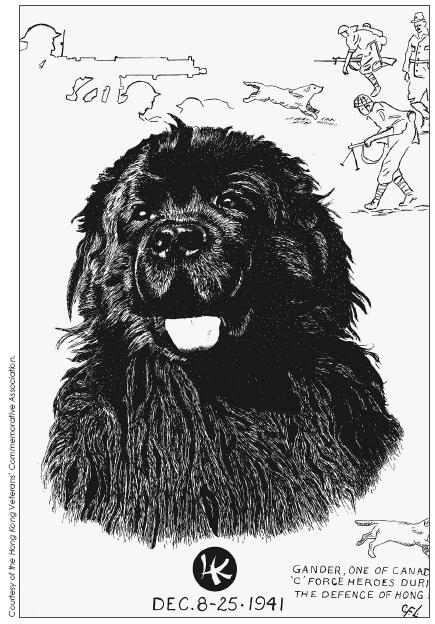

Gander's Citation

For saving the lives of Canadian Infantrymen during the Battle of Lye Mun on

Hong Kong Island in December 1941. On three documented occasions “Gander”

the Newfoundland mascot of the Royal Rifles of Canada engaged the enemy as

his regiment joined the Winnipeg Grenadiers, members of Battalion Headquarters

“C” Force and other Commonwealth troops in their courageous defence of the

Pen and ink sketch of Gander.

Island. Twice “Gander's” attacks halted the enemy's advance and protected groups

of wounded soldiers. In a final act of bravery the war dog was killed in action

gathering a grenade. Without “Gander's” intervention many more lives would

have been lost in the assault.

The medal was given to the Canadian War Museum for its exhibit on the Defence

of Hong Kong. Sadly, the PDSA's hope that the exhibition of Gander's medal would

remind generations to come of Canada's courageous canine has not been realized.

The medal was exhibited for a time, but has since been removed. At present, Gander's

story is no longer part of the Hong Kong exhibit at the War Museum, and his PDSA

Dickin Medal is kept in a secure vault in the basement of the Museum.

The history of military conflict abounds with stories and descriptions of how animals served alongside human combatants. Whether as a much loved mascot providing moral support or a link to home, or as a working animal trained to carry messages, sniff out bombs, or charge into battle with a soldier perched upon its back, animals have been as much a part of military history as the battles themselves. The contributions of these creatures, who never had a choice about whether or not they wanted to “go off to war,” have been recognized by many of the nations for which they served.

In the Canadian capital of Ottawa, the stone wall at the entrance to the Memorial Chamber in the Parliament buildings has carvings depicting animals and the words, “The Humble Beasts that Served and Died.” In Lille, France, a statue of a woman with a pigeon sitting in her hands stands as a memorial to all of the carrier pigeons who transported messages during the wars. Great Britain has perhaps the most impressive memorial, The Animals in War Memorial, which was unveiled in 2004 and is located in Hyde Park. The inscription reads, “Animals in War. This monument is dedicated to all the animals that served and died alongside British and allied forces in wars and campaigns throughout time. They had no choice.”

As workers, animals have served a multitude of purposes throughout the history of war. Dogs have routinely been used to search for both mines and injured people, and more recently dolphins and sea lions are being trained to search for underwater mines. Mules, camels, elephants, and oxen have traditionally been used for the transport of supplies, while horses have carried both men and supplies into battle. Over eight million horses were killed during the First World War alone. Pigeons were used extensively to carry messages during both World Wars, and in the Second World War over 200,000 were used, with only one in eight ever returning home.

1

Even glow-worms have served, providing light in the trenches during the First World War so that the soldiers could read.

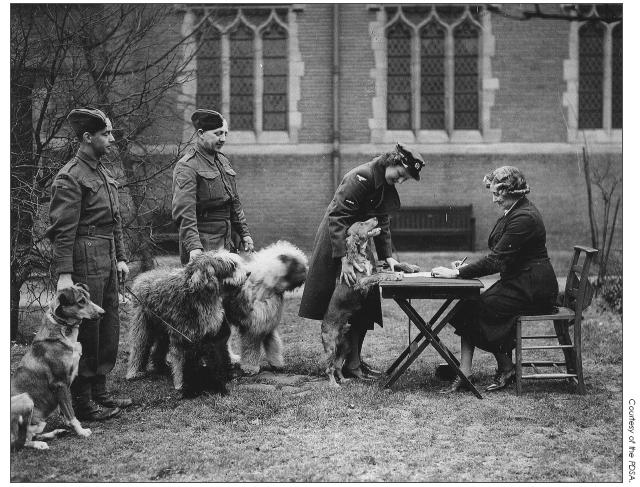

British soldiers in line to register their mascots as members of the Allied Forces Mascot Club.

During the First World War one of the most famous working animals was Murphy, the donkey. In 1915, he was shipped to Turkey, where Australian and New Zealand troops were fighting Turkish and German forces at Gallipoli. Along with the other donkeys, Murphy carried supplies up and down the hills adjacent to the beach. One day, an Australian soldier named John Simpson Kirkpatrick (more commonly known as Simpson) saw Murphy carrying his load of supplies

and came up with another idea for the donkey's use. He threw a blanket over Murphy's back to act as a saddle and rode the little donkey through the hills searching for injured soldiers. Simpson would put the injured men on Murphy's back, and Murphy would carry them down to the medical unit. The idea worked well and each day Simpson and Murphy would set off in search of wounded, scouring the hills from dawn until dusk, always under threat of enemy fire. Their hard work resulted in the rescue of over 300 wounded men. On May 19, 1915,

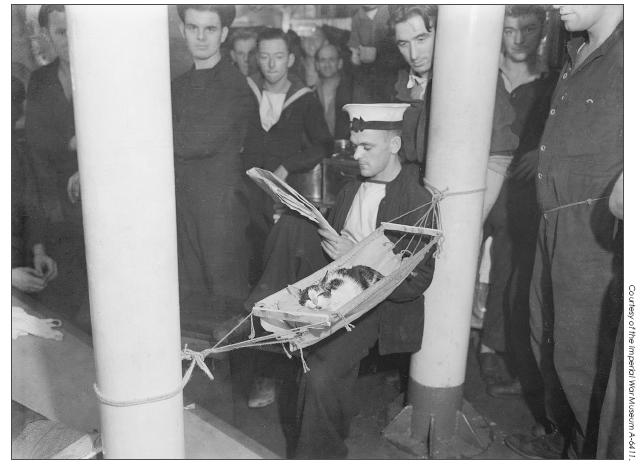

Polish sailors and their ships' cats, 1940.

Convoy the ship's cat of HMS

Hermione

, November 26, 1941.

while on one of their patrols, Simpson and Murphy came under heavy enemy fire, just after they placed a wounded man on the donkey's back. Simpson was killed. Legend has it that Murphy continued back to the army hospital with the injured man on his back and then led rescuers back to Simpson's body. Other sources claim that Murphy was killed in the initial gunfire barrage. Whatever the case, the Australians thought enough of the pair's contributions to erect a statue of Simpson and Murphy outside the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

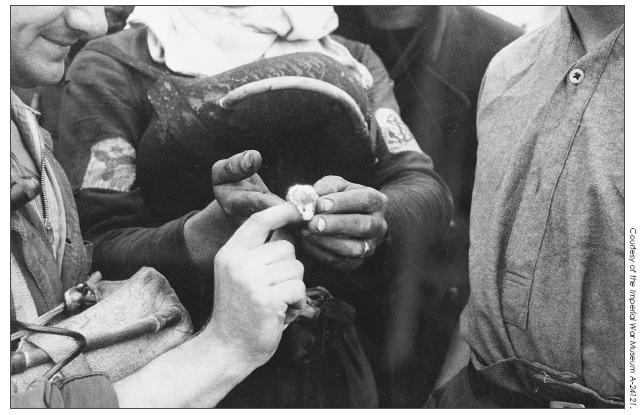

Ship's mascot Ighty who was injured at Dieppe, Sepâtember 1942.

Humankind's bond with animals fostered the need for many soldiers to bring mascots with them into battle, or to adopt an animal while serving in the military. A pet, something to love and care for, is often a welcome distraction from the horrors of war. During the Second World War the PDSA formed the Allied Forces Mascot Club to recognize the importance of animal mascots and the variety of roles that they played while serving with the armed forces. Hundreds of soldiers and sailors registered their mascots for membership in the club, and each animal

Eustace the mouse, on board

LCT 947

, Normandy, June 6, 1944.

member received a certificate and a badge to recognize their wartime service. The mascots took on all shapes and sizes of many different animals.

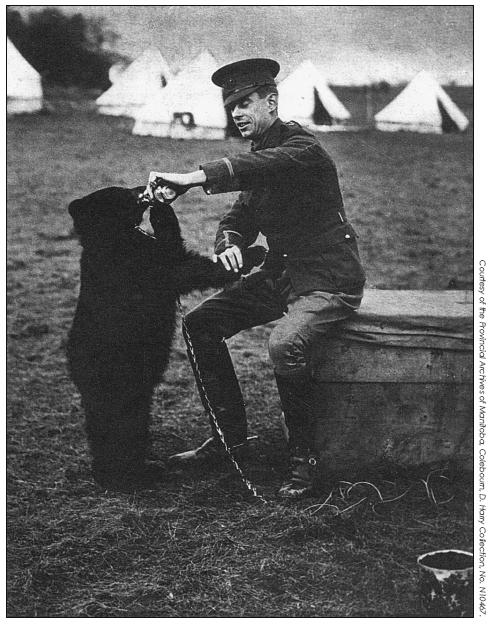

In addition to Sergeant Gander, there are two other relatively well-known Canadian animals that set off to war with their masters. The first never actually made it to the battlefields, but is probably the most famous, being better known as the bear that inspired the creation of Winnie the Pooh. In 1914, just after the outbreak of the First World War, a young veterinarian from Winnipeg, Harry Colebourn, set off for the newly created army training camp at Valcartier, Quebec. At a train stop in White River, Ontario, Harry befriended a small black bear cub whose mother had been killed by a trapper. He paid twenty dollars for her and

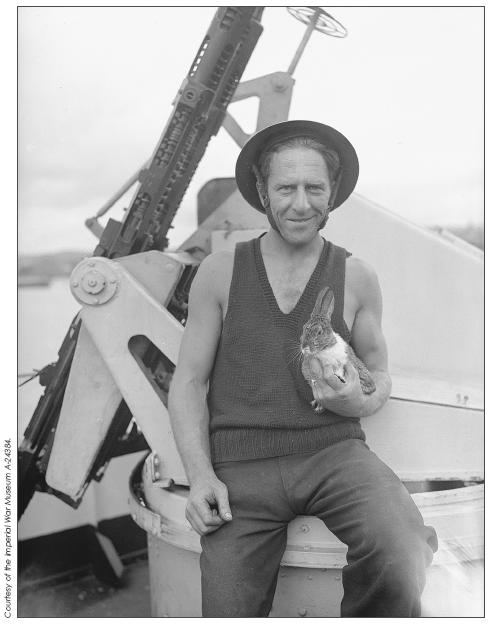

Muncher, the rabâbit mascot of the HMCS

Haida

.