Read Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm Online

Authors: Rene Almeling

Tags: #Sociology, #Social Science, #Medical, #Economics, #Reproductive Medicine & Technology, #Marriage & Family, #General, #Business & Economics

Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm (27 page)

BIOLOGICAL FACTORS IN SOCIOLOGICAL ANALYSES

This book also contributes to debates among social scientists about how to assess the role of biology in social processes. Feminists have historically avoided biological explanations, which is understandable given the regularity with which sex differences are referenced to deflect criticism of social inequalities. But decades of research on women’s disadvantages do not lead one to expect a market in which women are more valued than men and where having a child can actually make a woman a more desirable candidate. These unexpected findings are explained, however, once the body is taken into account, both in its materiality, including differentiated reproductive organs, and in the meanings associated with this differentiated materiality, such as economic interpretations (e.g., eggs as a scarce resource) and cultural readings (e.g., women as nurturing).

Thus, as Judith Butler theorizes, the body does matter, but biology does not provide a set of static facts to be incorporated into sociological analyses, because biological factors alone do not predict any particular outcome. Indeed, empirical investigations into the meaning of reproductive cells and bodies reveal considerable variation in different social contexts. For example, Emily Martin finds that metaphors in medical textbooks privilege male bodies. However, in the medical market for eggs and sperm, some of these same “biological facts” result in higher monetary compensation and more cultural validation for women—validation that is based on a different set of gendered stereotypes about caring femininity and breadwinning masculinity.

But it is not only gender that influences the valuation of sex cells. Donation programs have difficulty recruiting diverse donors, so Asian and African American women might be paid a few thousand dollars more, and sperm banks reported relaxing height restrictions to accommodate Asian and Hispanic men. This paradoxical finding, that women of color are often compensated at higher levels for their reproductive material than are white women, is illuminated by intersectionality theory, which contends that gender, race, and class can combine in unpredictable ways, sometimes resulting in advantage or disadvantage depending on the social context.

4

In this market, race and ethnicity are biologized,

as in references to Asian eggs or Jewish sperm, and these are some of the primary sorting mechanisms in donor catalogs, along with hair and eye color. This routinized reinscription of race at the genetic and cellular level in donation programs, which as medicalized organizations offer a veneer of scientific credibility to such claims, is worrisome given our eugenic history.

5

In sum, it is essential for sociologists to attend to biological factors while simultaneously resisting essentialized biological explanations. Although reproductive cells and reproductive bodies are the salient biological factors in this market, sociologists working in other contexts are likely to encounter assumptions about other kinds of bodily difference. Incorporating biological factors into sociological analyses can also mean measuring the physical effects of gendered expectations. For example, although Arlie Hochschild discusses the biological basis of emotion, she does not focus on the biological

consequences

of different kinds of emotional labor. She concludes that female flight attendants experience more cognitive dissonance than do male debt collectors, but the long-term biological effects of manufactured smiling may actually be less severe than those of manufactured anger, which has clear cardiovascular implications.

6

In another example of physical effects, it is important for sociologists to explore how embodied experiences can vary by social context, as in egg donors’ blasé descriptions of IVF and sperm donors’ fluctuating sperm counts. There remains much work to be done in specifying the mechanisms through which the bodies of those who make markets interact with other cultural, economic, and structural factors in shaping those markets.

MARKETS FOR BODILY GOODS

In this section, I turn to markets for other kinds of bodily goods and briefly consider how the findings from this book might shed new light on the trade in blood, organs, surrogacy, and sex.

7

Specifically, I draw attention to the ways in which the market for eggs and sperm in the United States is both like and unlike markets for these other goods and services, including the extent to which each good is associated with the

gender of the provider, whether providers receive direct payment, and whether the monetary exchange is stigmatized and/or legal.

Comparing how eggs and sperm are commodified highlights the importance of gendered cultural norms in structuring the organization and experience of the market for sex cells, but it is an open question whether such norms play such a significant role in markets for other bodily goods. For example, blood and organs are not sexed bodily goods in the same way that eggs and sperm are. They certainly come from male and female bodies and are transferred into male and female bodies, but blood and organs from a female can usually be transferred into a male and vice versa. However, this does not mean that gender norms are insignificant. To give just one example, scholars in Germany recently took up the long-identified gender discrepancy in living kidney donation in which women are more likely to be donors and men are more likely to be recipients. They found that part of the discrepancy is due to the fact that

mothers

donate to their children more often than do

fathers

and conclude by pointing to the power of gendered expectations, especially those of women as caregivers to children, in swaying decisions to donate.

8

Another contrast is that, unlike egg and sperm donors, blood and organ donors in the United States are generally not paid, though there is a thriving secondary market among medical professionals for these goods. Kieran Healy’s research clearly demonstrates the importance of organizational variation in shaping markets for blood and organs.

9

His findings raise an interesting question, however, about whether such variation results in different experiences for donors, particularly compared with countries that

do

allow direct payments or where black markets exist.

10

Consider the following two hypothetical kidney providers. The first is a poor man living in a shantytown in a developing country. He is paid $3,000 cash for one of his kidneys, which is removed in unsanitary conditions and transferred to a wealthy medical tourist. The second is a middle-class American man living in the suburbs. He is given a $3,000 credit toward health insurance for agreeing to donate his kidneys after his death. Both of these men and their kidneys are commodified, yet the organization and experience of the market is likely to be dramatically different. This seems obvious, but, in fact, bioethical treatments of commodification would generally

lump these sorts of examples together because of the simple fact that monetary value has been assigned to part of the human body.

In both surrogate motherhood and prostitution, there is no question that gender norms are important in shaping market processes, but there is significant variation in how it is that gender matters. For example, recent ethnographic studies of surrogacy in Israel and India reveal differences in the commodification of gestation that depend in part on how gift rhetoric intertwines with ideals of motherhood and economic necessity in each national context.

11

My explanation for the dynamics at play in the American market for sex cells might not hold in other contexts. However, it does seem to hold for the surrogacy market in the United States, where the practice of paying women to carry a pregnancy continues to be controversial, so much so that some states have prohibited payments or banned the practice altogether. Even more than egg donors, surrogates risk being portrayed as mothers who hand over children for cash, and indeed, social scientists have documented the same “gift of life” rhetoric among surrogacy agencies, surrogate mothers, and their recipients.

12

Although men cannot (yet) be surrogates, they can be prostitutes. However, as in egg and sperm donation, there are few studies that directly compare male and female sex work. When considered together, though, studies on particular aspects of the sex trade suggest it, too, exhibits significant variation in the organization and experience of the market, both by the gender of the provider and the gender of the consumer, as well as race, class, sexuality, and nationality. For example, Trevon Logan culled quantitative data from a national website advertising male escorts in the United States and found that the men serve a wide range of customers, from gay-identified men to heterosexually-identified men. Those who advertise more “masculine” behaviors charge higher prices for their services.

13

In a different national context, Don Kulick’s ethnographic study of Brazilian

travestis

reveals how masculinity and sexuality come together to create a market in which people who are born with male genitalia dress as women and have sex with men for both money and pleasure.

14

Turning to female prostitution, Elizabeth Bernstein’s comparative research in San Francisco, Amsterdam, and Sweden traces the shifting

structure of this market over the past several decades. In particular, she considers how such changes have affected the embodied experiences of sex workers. Bernstein also finds inspiration in Viviana Zelizer’s research, and she concludes with a call for closer empirical attention to variation in such markets. “Rather than taking commodification to be a self-evident totality, . . . I stress the ethical necessity of distinguishing

between

markets for sexual labor, based on the social location and defining features of any given type of exchange.”

15

Now, in contrast to markets for blood, organs, and surrogacy, altruistic rhetoric does not appear to be a salient feature of the market for sex. It is difficult to imagine male or female prostitutes claiming to be “donors” of sex, which raises the question of when it is that gift talk and bodily commodification can coexist. In keeping with the significance of gender, gift rhetoric may be more likely to appear, and to be more “sticky,” when it comes to bodily goods that women donate because of cultural ideals of women as caring and selfless. Along the same lines, production rhetoric may appear more often for goods that men donate. However, this still does not explain why gift rhetoric does not appear in female prostitution. Lesley Sharp suggests that gift talk and bodily commodification are especially likely to coexist in medical settings, and that would certainly hold for the cases discussed here (blood, organs, and surrogacy versus prostitution).

16

Another potential explanation is that prostitution does not violate the market/family divide in quite the same way as egg donation and surrogacy, markets in which children are being created.

This book has focused on how gendered norms influence the market for sex cells, but as is clear from several of the examples in this section, racial and class-based inequalities, among others, are likely to be just as powerful in shaping processes of bodily commodification. Little is known about when and how various social categories come to matter in markets for bodily goods, but one area where there have been several detailed empirical studies is the use of racial categories in the field of genetics.

17

As Rayna Rapp points out, it is the newest technologies that seem to attract the oldest stereotypes.

18

SEX CELLS

Sex does indeed sell in the medical market for eggs and sperm. Inside every reproductive cell are tightly coiled strands of DNA, and the value of this genetic material is understood through the lens of the donor’s biological sex. Those who work to maintain this market, from buyers and brokers to sellers and regulators, calibrate their actions in ways that align with cultural norms of maternal femininity and paternal masculinity. The result is a classic evocation of the gendered division of labor: women’s bodies are managed though the emotional work of caring about recipients, and men’s bodies are regulated via a paycheck conditioned on sperm count. Nevertheless, this classic evocation produces surprising results. Women are paid much more than men, but the connection they establish with recipients, along with the availability of gift rhetoric, forestalls other potential understandings of remunerated donation, such as being paid for body parts. Men are not encouraged to feel any such connection with recipients, so although they are exempt from this form of emotional labor, the result is that they experience paid donation as a job, which leads to feelings of objectification and alienation. Whether eggs or sperm, blood or organs, surrogacy or sex, the social process of assigning economic value to the human body is the result of a confluence of factors. The characteristics of the people and the parts, the flows of supply and demand, and the historical and cultural context all come together to produce variation in both the structure and experience of the market.

APPENDIX A

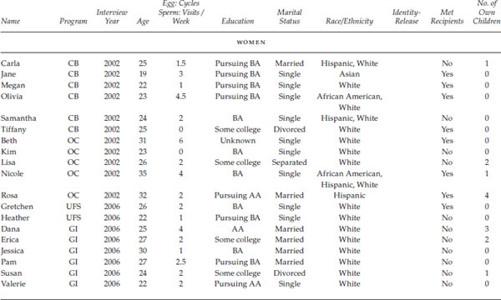

Egg and Sperm Donors’ Characteristics at Time of Interview