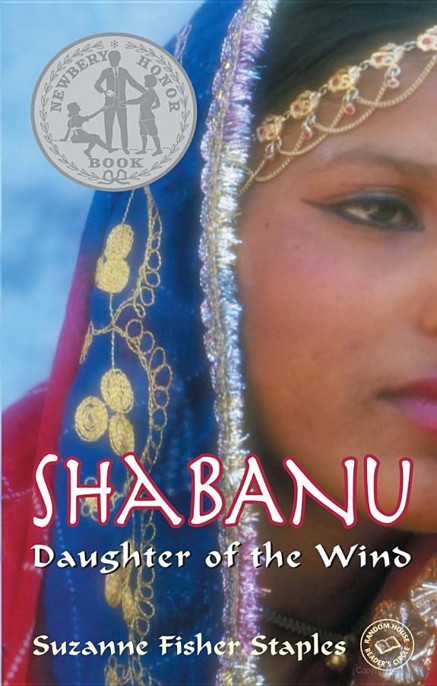

Shabanu

Authors: Suzanne Fisher Staples

To honor and to obey…

“Shabanu, you are as wild as the wind. You must learn to obey. Otherwise … I am afraid for you,” Mama says, her face serious

.

“In less than a year you’ll be betrothed. You aren’t a child anymore. You must learn to obey, even when you disagree.” I am angry to think of Dadi or anyone else telling me what to do. I want to tell her I spend more time with the camels than Dadi, and sometimes when he asks me to do a thing, I know something else is better. But Mama’s dark eyes hold my face so intently that I know she really is afraid for me, and I say nothing

.

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM DELL LAUREL-LEAF BOOKS

HAVELI

, Suzanne Fisher Staples

SHATTERED: STORIES OF CHILDREN AND WAR

Edited by Jennifer Armstrong

DAUGHTER OF VENICE,

Donna Jo Napoli

AN OCEAN APART, A WORLD AWAY,

Lensey Namioka

GODDESS OF YESTERDAY,

Caroline B. Cooney

ISLAND BOYZ: SHORT STORIES,

Graham Salisbury

LUCY THE GIANT,

Sherri L. Smith

THE LEGEND OF LADY ILENA,

Patricia Malone

LORD OF THE NUTCRACKER MEN,

Iain Lawrence

WHEN ZACHARY BEAVER CAME TO TOWN

Kimberly Willis Holt

To the people of Cholistan

Published by

Dell Laurel-Leaf

an imprint of

Random House Children’s Books

a division of Random House, Inc.

New York

Copyright © 1989 by Suzanne Fisher Staples

Map copyright © 1989 by Anita Carl and James Kemp

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law. For information address Alfred A. Knopf.

Dell and Laurel are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web!

www.randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at

www.randomhouse.com/teachers

eISBN: 978-0-375-98589-8

RL: 6.5

Reprinted by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf

v3.1

Names of Characters

italicized syllable is accented

Shabanu (Shah-

bah

-noo)—Narrator, eleven years old at the story’s beginning

Phulan (

Poo

-lahn)—Shabanu’s sister, age thirteen

Mama

(Mah-

muh)—Shabanu’s mother

Dadi

(Dah-

dee)—Shabanu’s father

Dalil Abassi (Dah

-libl

Uh

-bah-

see)—Dadi’s proper name

Jindwadda Ali Abassi (Jihnd

-wah-

duh

Ah

-lee Uh

-bah-

see)—Dadi’s father

Adil (Uh

-dihl)

—A married male cousin

Hamir (

Huh

-mihr)—The cousin to whom Phulan has been promised in marriage

Murad (Moo

-rahd)

—Hamir’s brother, whom Shabanu will marry when she comes of age

Sardar Nothani Bugti (Sar

-dahr

Nuht-

hah

-ni

Buhg-

tee)—Leader of a clan from the Bugti tribe of Baluchistan

Wardak (

Wohr-

duhk)—An Afghan rebel leader

Sharma

(Shahr

-muh)—A female cousin of Mama’s and Dadi’s

Fatima (Fah-

tee

-muh)—Sharma’s daughter

Nawab of Bahawalpur (Nuh

-wahb

of Buh-

bah

-wuhl-poor)—The hereditary ruler of the old kingdom of Bahawalpur, now a district of modern Pakistan

Sulaiman (Soo-

leh

-mahn)—Keeper of the tombs at Derawar

Shahzada (Shah-

zah

-duh)—The guard at Derawar Fort

Bibi Lal

(Bee-

bee Lahl)—Murad and Hamir’s mother

Sakina (Sah

-kee

-nuh)—Bibi Lal’s youngest daughter

Kulsum (

Kool

-suhm)—The widow of Lal Khan, Murad and Hamir’s older brother

Nazir Mohammad (

Nuh-

zeer Muh-

hah

-muhd)—A landowner at the village of Mehrabpur

Rahim (Ruh

-heem)

—Nazir Mohammad’s older brother

Spin Gul (Spihn

Gool)

—An officer of the Desert Rangers

Colonel Haq (Colonel

Huhq

)—The commander of the Desert Rangers’ headquarters at Yazman

Phulan and I

step gingerly through the prickly gray camel thorn, each of us balancing a red clay pot half filled with water on our heads. It was all the water we could get from the

toba

, the basin that is our main water supply.

Our underground mud cisterns are infested with worms. We’ll dig new ones when the monsoon rains come—if they come.

The winter sky is hazed with dust. There has been no rain in nearly two years, and the heat of the Cholistan Desert is as wicked as if it were summer.

Phulan walks with her eyes down, her feet shuffling, kicking up puffs of sand that is light as dust. Her name means “flower,” and she is beautiful when she smiles.

I am Shabanu. Mama says it’s the name of a princess, but my red wool shawl has worn so thin I can see through it. I pull it tighter around me and pretend it’s a

shatoosh

. It’s said that real princesses wear

shatoosh

shawls so fine they can pass through a lady’s ring.

In the courtyard that circles our round, thatched huts, Mama and Auntie have made a fire, and a kettle keeps warm beside it for tea. Even when we are down to the last of our water we have tea. Grandfather leans against the courtyard wall, chin on his chest, his turban nodding in rhythm to his snores.

Mama sits with yards of yellow silk in her lap, stitching one of Phulan’s wedding dresses. She has embroidered silver and gold threads, mirrors, and tassels into the bodice. You’d think Phulan was the princess!

Mama holds up the tunic and measures it against Phulan’s shoulders and chest. She laughs, her teeth gleaming in the opal haze of the setting sun.

“If you don’t grow breasts soon, this will look like an empty goatskin,” she says, her strong brown fingers plucking at the extra silk in the curved bodice. She has made it big enough to fit Phulan when she’s grown. Phulan is thirteen. She will marry our cousin Hamir this summer

during the monsoon rains. The monsoon, God willing, will bring food for our animals and fruit to the womb of Phulan.

“If God had blessed you with sons, we wouldn’t have to break our fingers over wedding dresses,” says Auntie as she sews the hem of the skirt. Her sons, ages three and five, play noisily nearby.

Mama ignores her and sets the silk aside, for Dadi will come soon from tending the camels, and he’ll be hungry. She dips her tall, graceful frame through the doorway of our hut and comes out with a large wooden bowl. Squatting before the fire, she kneads water into wheat flour to make

chapatis

.

“I worry,” Auntie goes on, her fingers flying over the yellow silk. “You’ll spend your life’s savings on two dowries and two weddings. Without a son, who will bring a dowry for you? And who will take care of you when you’re old?”

Mama pulls at the dough and slaps it into disks. She whirls the flat bread onto the black pan over the fire.

“Mama and Dadi are happy,” I say, sticking my chin out.

“What do you know?” Auntie asks, folding her pudgy arms over her bosom. “You’re nothing but a twig.”

“They laugh and sing. Aren’t you happy, Mama?” Mama smiles, and her eyes are merry in the glow of the fire. Auntie almost never laughs.

“Don’t worry, little one,” says Mama. “You and Phulan are better than seven sons.” Auntie purses her lips and picks up her sewing again.

Phulan covers her nose and mouth with her shawl, and her eyes tell me she is trying to keep from laughing. Auntie gives us a sour look and bends over her work.

Dadi and I bought the silk—yards and yards of red and turquoise and yellow the color of mustard blooms—on our way from the great fair at Sibi last year.

Dadi comes into the circle of the fire as the light is leaving the sky and the stars begin to peep out from their sapphire curtain. He is no taller than Mama, but his shoulders are broad and the

lungi

tied around his waist covers the thick muscles of his thighs and buttocks.

“How much water is there?” he asks, crossing his ankles and sitting beside the fire. He rubs his eyes. They are red, irritated by blowing sand. Most of the desert plants have died from lack of rain.

Phulan fetches Dadi’s

hookah

and lights it with a stick from the fire. Dadi sucks on the snakelike mouthpiece, and the sweet smoke of brown sugar and tobacco bubbles through the water in the base of the long pipe.

Mama looks up at him from across the fire.

“We have two goatskins, one half full. One pot is empty.”

Phulan’s eyes are intent on Dadi. He has just come from the

toba

, where the camels gather each day to drink.

“What’s left in the

toba

is not fit for the camels, let alone for us. We must pack tomorrow.”

We are the people of the wind. When hot summer winds parch the land, we must move to desert settlements where the wells hold sweet water. When the monsoon winds bring

rain, we return to the dunes. But this year and last the monsoons failed, and we must go now to Dingarh, an ancient village where the wells are deep.

“You’ll take me away, and I’ll never come back to Cholistan,” Phulan says softly, looking at her hands.

“Nay, nay,” says Mama, leaving her

chapati

making to pull Phulan into her arms. “We’ll settle at Dingarh before Dadi and Shabanu leave for Sibi next month.” Mama rocks Phulan against her. Dadi says nothing. His face is tired from worry, and his black hair is disheveled under his turban.

I secretly count the hours until we leave for Sibi! It will be just Dadi and me and the camels. Phulan hasn’t gone since her betrothal to Hamir. Our camels are always the finest at the fair, and Dadi is a good businessman. This year we’ll sell fifteen to pay for Phulan’s wedding.

The winter night is cold after the intense heat of the day, and Phulan and I huddle under the quilt for warmth. There is scarcely any space between the stars. I watch them as Phulan talks about having babies. No matter how I try, I can’t imagine her a mother. But her monthly bleeding began, and Mama and Dadi quickly set her wedding date for the summer, after the fasting month of Ramadan.

“You’ll have new clothes too,” she says, hugging me close. I’ve worn the same tunic over the same skirt three years, since my eighth birthday. They used to be blue as the winter sky, with red flowers and ribbons. But now they have no color at all. The buttons are gone, the sleeves are up to my elbows, and the skirt is nearly at my knees.