Shadow of the Silk Road

Read Shadow of the Silk Road Online

Authors: Colin Thubron

Shadow of the Silk Road

For Paul Bergne

The journey recorded here was broken by fighting in northern Afghanistan. The section delayed there was travelled the following year, in the same season.

In the midst of political uncertainty, the identities of several people described in the narrative have been disguised.

In the dawn the land is empty. A causeway stretches across the lake on a bridge of silvery granite, and beyond it, pale on its reflection, a temple shines. The light falls pure and still. The noises of the town have faded away, and the silence intensifies the void–the artificial lake, the temple, the bridge–like the shapes for a ceremony which has been forgotten.

As I climb the triple terrace to the shrine, a dark mountain bulks alongside, dense to the skyline with ancient trees. My feet sound frail on the steps. The new stone and the old trees make a soft confusion in the mind. Somewhere in the forest above me, among the thousand-year-old cypresses, lies the tomb of the Yellow Emperor, the mythic ancestor of the Chinese people.

A few pilgrims are wandering in the temple courtyard, and vendors under yellow awnings are offering yellow roses. It is quiet and thick with shadows. Giant cypresses have invaded the compound and now stand, grey and aged, as if turning to stone. One, it is said, was planted by the Yellow Emperor himself; another is the tree where the great emperor Wudi, founder of the shrine two thousand years ago, hung up his armour before prayer.

The pilgrims are taking photographs of one another. They pose gravely, accruing prestige from the magic of the place. Here their past becomes holy. The only sound is the rustling of the bamboo and the murmuring of the visitors. They pay homage in this temple to their own inheritance, their pride of place in the world. For the Yellow Emperor invented civilisation itself. He brought China–and wisdom–into being.

The woman is gazing at a boulder indented by two huge footprints. Slight and girlish, she jumps at the sight of a foreigner. Foreigners don’t come here–she laughs through her fingers–she is sorry. The footprints, she says, belong to the Yellow Emperor.

‘Not really?’

‘Yes. One of his concubines used them to make boots. He invented boots.’

We walk for a moment where memorial stones are carved with the tribute of early emperors, and come at the court’s end to the Hall of the Founder of Human Civilisation. Its altar is ablaze with candles and incense, and heaped with plastic fruit. The woman’s gaze, when I question her, stays candid on mine. The Yellow Emperor invented writing, music and mathematics, she says. He discovered silk. This was where history began. People had been coming here generation after generation. ‘And now you too. Are you from your government?’ But her eyes dip to my worn trousers and dusty trainers. ‘A teacher?’

‘Yes,’ I lie. Already a new identity is unfurling: a teacher with a taste for history, and a family back home. I want to go unquestioned.

So that’s why you speak Mandarin, she says (although it is poor, almost toneless). ‘And where are you going?’

I think of saying Turkey, the Mediterranean, but it sounds preposterous. I hear myself answer: ‘Along the Silk Road to the north-west, to Kashgar.’ And this sounds strange enough. She smiles nervously. She feels she has already reached out too far, and turns silent. But the unvoiced question

Why are you going?

gathers between her eyes in a faint, perplexed fleur-de-lis. This

Why?,

in China, is rarely asked. It is too intrusive, too internal. We walk in silence.

Sometimes a journey arises out of hope and instinct, the heady conviction, as your finger travels along the map:

Yes, here and here…and here. These are the nerve-ends of the world…

A hundred reasons clamour for your going. You go to touch on human identities, to people an empty map. You have a notion that this is the world’s heart. You go to encounter the protean shapes of faith. You go because you are still young and crave excitement,

the crunch of your boots in the dust; you go because you are old and need to understand something before it’s too late. You go to see what will happen.

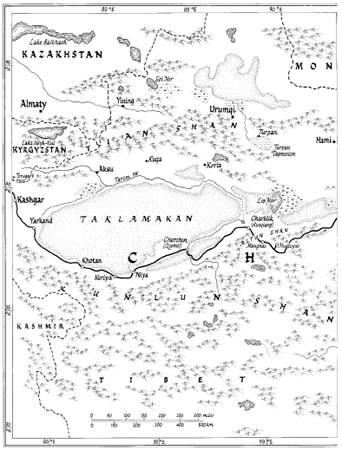

Yet to follow the Silk Road is to follow a ghost. It flows through the heart of Asia, but it has officially vanished, leaving behind it the pattern of its restlessness: counterfeit borders, unmapped peoples. The road forks and wanders wherever you are. It is not a single way, but many: a web of choices. Mine stretches more than seven thousand miles, and is occasionally dangerous.

But in the temple of the Yellow Emperor, the woman’s gaze has drifted north. ‘He was buried up there on the mountain,’ she says. ‘It’s written that people tugged at the emperor’s clothes as he flew to heaven, trying to pull him back. Some say that only his clothes are buried there. But I don’t think this is true.’ She speaks softly, with a tinge of unexplained sadness. ‘The grave is quite small, not like those of later emperors. I think life was simpler in those days.’

We walk for a minute longer under the eaves of the temple. Then, suddenly, the quiet is shattered by the stutter of power-drills and the groan of dump-trucks.

‘They’re building the new temple,’ she says. ‘For celebrations and conferences. This one’s too small. The new one will hold five thousand people.’

Later I peer down from the hillside on the building site where it will be. I imagine the stressless, unchanging temple-pavilions of China rising from their wan granite. This place, Huangling, is only a hundred miles north of modern Xian, but is lost deep in another time of erosion and poverty. Who will come?

But the whole site is resurrecting as a national shrine, and already the older temple is filled with the memorial stelae of China’s statesmen offering homage to ‘the father of the nation’. Here is the stone calligraphy of Sun Yatsen from 1912, and of Chiang Kai-shek, predictably coarse; of Mao Zedong, who was later to condemn the Yellow Emperor as feudal; of Deng Xiaoping and the hated Li Peng.

The clamour of restoration dies as you climb the track where it snakes through the cypress woods. From somewhere sounds the drilling of a woodpecker, and human voices echo and fade above

you. Here and there a yellow flag on a bamboo pole marks the way. You are sinking back in time. Close to the summit the path becomes a stone stairway, and the trees turn phantasmal, their trunks twisted like sticks of barley-sugar or wrenched open on swirling slate-blue veins. Here the grandest mandarin, even the emperor, abandoned his sedan chair and approached the mausoleum on foot.

For there is little in the end–from music to the calendar–whose discovery is not attributed to the Yellow Emperor. He reigned for a hundred years until 2597

BC

before ascending to heaven on a dragon. It was he who instituted the festivals of earth and silk. After him the reigning emperors, from a remote time, inaugurated the year by ploughing a ritual furrow, while their empresses offered cocoons and mulberry leaves at the altar of his wife Lei-tzu, the Lady of the Silk Worms.

It was Lei-tzu, in legend, who discovered silk. While walking in her garden, she noticed a strange worm gorging on mulberry leaves. For several days she watched it spinning itself a golden net, and imagined it the soul of an ancestor. Then she saw it close itself away, and thought it dead–until the reincarnate moth burst from its cocoon. Toying, mystified, with its minute broken shroud, the empress mistakenly dropped it into her tea. Idly she picked at the softened fibre, then began to unwind it, with growing astonishment, into a long, glistening filament of silk. In time she became the teacher of silk-weaving and of the rearing of the mysterious worm, and she was deified at her death and placed in the sky in the celestial home of Scorpio, the constellation Silk House.

You reach the summit of the hill, which the ancients called Mount Qiao. Incense and sunlight filter through the trees. People have made sacrifice here since the eighth century

BC

, and the emperor Wudi built a prayer platform, now softly decaying. The few attendants stare at you in mute surprise. Beside the platform, cauldrons the size of cement-mixers are stuffed with joss sticks, and a suspended log is being swung at a monstrous bell, whose clang shakes the woods.

Beyond, enclosed in a sombre wall so crowded by cypresses that it is almost invisible, rises the grave-mound of the Yellow Emperor.

It is only twelve feet high, rank and tufted by shrubs. You circle it tentatively on a path of beaten earth. The funeral stele planted before it reads: ‘The Dragon-rider on Mount Qiao’. But you wonder how he really died, and who he was. Some historians believe that the dragon is the memory of a meteor, in whose cataclysmic fall the emperor vanished. Its remnants have been identified nearby.

As you wander the rim of the mountain, the enigma deepens. Far on all sides the arid hills belong not to classical China but to a harsher world. This is where Shaanxi province points to Mongolia. Down its corridor the barbarian tribes–Huns, Turks, Mongols–descended south into China’s heartland, to the teeming cities of the Yellow River. In the more rigorous early histories, the Yellow Emperor was himself the forerunner of these: a clan leader who invaded from the north-west and unified the people in his path. It is curious. As if to still this nomad flood into controllable history, sages as long ago as the eleventh century

BC

slotted the conqueror into time as their ancestor. His colour changed to the yellow soil of inner China, where the wind-blown loess from the northern deserts settles into fertile fields. The notional shade of barbarian soils was black or red, and white the tint of death and of the West. But yellow was the colour of the world’s heart.

I circle back to the grave in confusion. Suddenly its mound is not a relic from some golden age, but the primitive barrow of a nomad chief. The father of China was not Chinese at all.

As for the Lady of the Silk Worms, she too fades from known history. The cultivation of silk had spread along the Chinese rivers long before her. More than six thousand years ago somebody in a Neolithic village carved a silkworm on an ivory cup, and archaeologists unearthed an artificially broken cocoon. Silk from the late third millennium

BC

turned up in a ruined city of Turkmenistan, and early sites have yielded spinning tools and even red-dyed silk ribbons.

In the forest clearing, by the prayer platform, one of the attendants opens his hand to me for money, hoping to sell me incense. But whimsically I choose another tribute. I swing the painted log–it moves swifter, heavier than I expect–against the

hanging bell. In the dark clearing it reverberates with a diffused clamour. Long after I’ve relinquished the log, the noise goes on. It booms over the platform, the forest, the tomb, like some melancholy knowledge. It is indefinably alarming. The other pilgrims turn to stare. The sound is more intrusive than any incense or candle.