Shakespeare: A Life (68 page)

Read Shakespeare: A Life Online

Authors: Park Honan

Tags: #General, #History, #Literary Criticism, #European, #Biography & Autobiography, #Great Britain, #Literary, #English; Irish; Scottish; Welsh, #Europe, #Biography, #Historical, #Early modern; 1500-1700, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #History & Criticism, #Shakespeare, #Theater, #Dramatists; English, #Stratford-upon-Avon (England)

maximum effect. Encouraged by his fellows he gave them what they

wanted, and always more in that his dramas brilliantly generate their

own renewal and affect people as no other plays have ever done. He

challenges the finest skills of a troupe, but it is also true that he

amply rewards those who act in his plays. He typically complicates a

text by altering the mood, tone, and tempo from line to line, and, in

effect, gives an actor a varying inner surface to exploit.

All of this argues his habitual closeness to actors, and probably his

need for a group. But his 'myriad-mindedness' arises from his own

intellectual and spiritual endeavour, his questing, his hope and

dissatisfaction. In the dialectic of his plays he looks for what is

valid, worthy, or possible in human nature, and comes at last to a

darkening. Henry VIII, as well as Palamon and Arcite in

The Two Noble Kinsmen

,

represent the commonness, the banality of our impercipience,

faithlessness, and blind, selfish passion, as if humanity's bleak,

disappointing past will yield to a bleaker and more tragic future. And

yet at the end of

Noble Kinsmen

in Theseus's speeches, Shakespeare perhaps implicitly gives thanks for life itself.

Easter came early in 1616, on 31 March. It might have been that

Easter, for all its blessed meaning, had not blessed the month of April.

A sufferer with typhoid fever knows incessant headache, lassitude,

and sleeplessness, then terrible thirst and discomfort. The features

begin to shrivel. Whatever the cause of his own fever, Shakespeare's

face in the effigy at Holy Trinity appears to be modelled on a

death-mask. His eyes stare, the face is heavy and the nose is small

and sharp. Because of the shrinkage of the muscles and possibly of the

nostrils, the upper lip is elongated.

44

It is, on the whole, likely that Shakespeare was so well nursed his

miseries lasted little longer than they might have done. But he died on

23 April, and two days later his body was taken into Holy Trinity's

chancel, which has ornamental stone knots of foliage, and on the south

side, the muzzled bear and ragged staff of the Earl of Warwick.

Shakespeare's grave slab was later probably altered, since it is too

short. But his sufferings were over, and the speeches of the exiled

brothers, Arviragus and Guiderius, in Act IV of

Cymbeline

might well do for his epitaph:

-409-

Fear no more the heat o'th' sun,

Nor the furious winter's rages.

Thou thy worldly task hast done,

Home art gone and ta'en thy wages.

Golden lads and girls all must,

As chimney-sweepers, come to dust.Fear no more the frown o'th' great,

Thou art past the tyrant's stroke.

Care no more to clothe and eat,

To thee the reed is as the oak.

The sceptre, learning, physic, must

All follow this and come to dust.Fear no more the lightning flash,

Nor th' all-dreaded thunder-stone.

Fear not slander, censure rash,

Thou hast finished joy and moan.

All lovers young, all lovers must

Consign to thee and come to dust.No cxorcisor harm thee,

Nor no witchcraft charm thee.

Ghost unlaid forbear thee.

Nothing ill come near thee.

Quiet consummation have,

And renownèd be thy grave.

-410-

|

-412-

-413-

|

It has been said that the year 1616 is an insignificant one in

theatrical history. In fact, both Shakespeare and Francis Beaumont

died in that year, but the King's men had learned to do without

Shakespeare the man while keeping his popular plays in repertoire, and

Beaumont, too, had left the theatre earlier. Actors carried on

without new dramas from older suppliers, and even the great Folio of

Shakespeare's plays broke no trade records in selling possibly 750

copies, or perhaps fewer, inside nine years. Why was curiosity about

the Stratford poet at a low ebb for some decades after 1623?

He was not alive to inspire new gossip -- and Inns of Court wits (for example) needed to be

au courant

in their enthusiasms. Views similar to Ben Jonson's on his Stratford

friend's lack of learning were repeated. That Shakespeare was 'never

any Scholar' and that 'his learning was very little' are claimed, by a

self-styled 'biographist', in the first formal sketch of him, in

Thomas Fuller

The History of the Worthies of England

( 1662); and Fuller's views are echoed in paragraphs about Stratford's poet for the rest of the century.

Furthermore, from about 1660 to the 1730s, with the canons of criticism

mainly set against them, Shakespeare's plays were often radically

adapted or purged of scenes of bloodshed, of their sensuously strong

imagery, and of other assumed faults. As Brian Vickers has written,

there is no 'comparable instance of the work of a major artist being

altered in such a sweeping fashion' (

Shakespeare: The Critical Heritage

, i,

1623-

1692

( 1974.)). Those who dwelt on his small learning, or his gross

diction and imagery, evidently did little to stimulate fresh enquiry

into the man.

Useful biographical

work really begins with John Aubrey's hectic notes, of about 1661 (but

not published until Andrew Clark's edition

-415-

in 1898), and Nicholas Rowe's short biography which introduces his edition of the plays in 1709.

Aubrey, born in 1626, jotted down what people had told him of the

great poet. He knew three members of the Davenant family, as Mary

Edmond has shown (

Rare Sir William Davenant

( 1987), ch. 2).

Stratford 'neighbours' spoke to him of Shakespeare's youthful feats as

the son of a 'Butcher'; they were doubtless wrong, but Aubrey also

sought out William Beeston (the youngest son of Christopher, the

playwright's former colleague in the Chamberlain's Servants), who is

the source of the remark that Shakespeare 'understood Latine pretty

well: for he had been in his younger yeares a Schoolmaster in the

Countrey'. Aubrey twice notes that the poet visited Warwickshire 'once

a yeare', and he comments on Shakespeare's personality, appearance,

and (it seems) on his not being a 'company keeper', in invaluable notes

which today call for unusual caution and tact on the part of critics

and biographers. The same might be said of the remarks of Nicholas

Rowe, a poet and playwright himself, who in 1709 relied on what Thomas

Betterton, the ageing tragedian, had picked up at Stratford, and partly

on hearsay, for his 'Some Account of the Life, &c. of Mr.

William Shakespear',

a forty page sketch which remained influential for a century.

By 1709, then, the three main channels for data about Shakespeare's

life (through Stratford, Oxford, or London) were being used. Lewis

Theobald's biographical sketch in his edition of the plays ( 1733)

acknowledges Rowe, but adds a history of Shakespeare's New Place and

discusses for the first time the licence King James I had granted in

1603 to the players. Neither William Oldys nor Edmond Malone completed

their lives of Shakespeare. Despite Oldys's interviews with Joan

Hart's descendants, and Malone's searches and scholarship, hard facts

about Shakespeare's life were slow to emerge. Facts and legends appear

in eighteenth-century editions of Shakespeare's plays, or for example

in notices by Thomas Tyrwhitt ( 1730-86) about allusions to the poet

in the two Elizabethan works, Greene

Groats-worth

and Meres

Palladis Tamia

.

By the end of the eighteenth century, materials for a full, factual

biography were accumulating. The known facts hardly exposed the poet's

intimate life. But, apparently, the practices of the late Tudor sonnet

-416-

vogue were forgotten or ignored (as they usually are today), and the

notion arose that Shakespeare's Dark Lady and Young Man of the Sonnets

were portraits of once living persons. Obviously for some, his

anguished private life was on record, though others in the new century

doubted that he had sketched in the Sonnets his exact relations with,

say, a Tudor bordello-keeper or a lord's mistress. To the notion that

the Earl of Pembroke was literally the Young Man of the Sonnets, the

Victorian biographer Charles Knight replied in 1841, Would Pembroke

suffer 'himself to be . . . represented in these poems as a man of

licentious habits, and treacherous in his licentiousness?' But by then

not only Pembroke but a real Dark Lady, as Samuel Schoenbaum puts it,

had 'sauntered into the best-loved sequence of lyric poems in our

language'.

Having unmasked forgeries,

edited Shakespeare documents, and studied the order in which the

plays were written, Edmond Malone died in 1812. His

Life of Shakespeare

was finished and published by James Boswell's son and namesake in

1821; Malone's fragment is still of interest for its authoritative

method and a few, rather cautious, speculations. With much less than

Malone's strict sense of fact, Nathan Drake

Shakspeare and his Times

( 1817) and Charles Knight

William Shakspere: A Biography

( 1843) began to explore inspirations the poet may have found in his

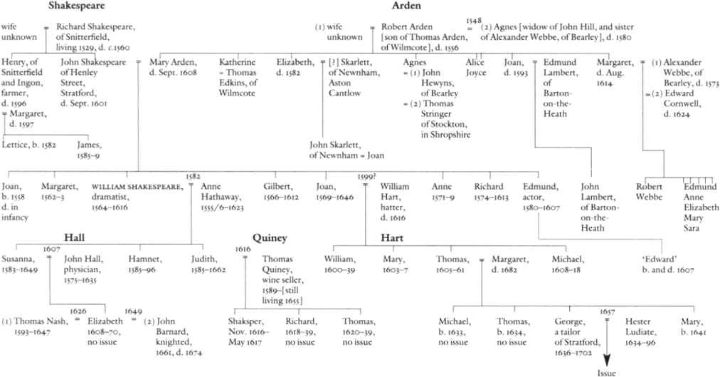

environment. Malone had given an impetus to genealogical research.

George Russell French

Shakspeareana Genealogica

( 1869) was

admired for its tables of descent, and more than a century later was

praised for establishing the exact 'relationship between Mary

Shakespeare's father and Walter Arden [of Park Hall], whose son Sir

John was Esquire of the King's body in the reign of Henry VII'.

Unfortunately, French, whose pedigrees are flawed, establishes no such

thing, and Mark Eccles's statement that 'there is no proof' that

Shakespeare was related to the wealthy Ardens of Park Hall, near

Birmingham, still holds good, though 'it is possible that Thomas

[Arden, Mary's grandfather] may have descended from a younger son of

that family' (

Shakespeare in Warwickshire

( 1961), 12).

At least two nineteenth-century writers, however, are still useful on

Shakespeare's life and locales. The antiquarian Robert Bell Wheler

History and Antiquities of Stratford-upon-Avon

( 1806), which he reissued abridged but with new data as his

A Guide

. . . ( 1814), as well as

-417-

Wheler's thirty-four volumes of MSS now at Stratford's Records

Office, have pertinent details. More than an antiquarian, J. O.

HalliwellPhillipps ( 1820-89) remains the most productive Shakespeare

scholar and biographer so far. His 559 printed works, not all of them

on the dramatist, are described in Marvin Spevack useful

James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps: A Classified Bibliography

( 1997). Halliwell also left a sea of scrapbooks, ledgers, letters,

and other MSS. Still indispensable is the final version of his

Outlines of the Life of Shakespeare

,

issued in expanding editions from 1881 to 1887 and offering, in its

vast, crammed appendices, not only some Shakespeare-related documents

printed entire, but a description of nearly every contemporary

reference to the playwright's father. Halliwell's boxes of MSS and 120

scrapbooks at the Folger, and some of his numerous MSS at Edinburgh

University Library, have useful notes on Shakespeare's career, the

actors, about thirty-two towns visited by the troupes,

play-performances, other shows (including funerals), as well as on

plague, harvests, food stocks, prices, and even the weather in the

1590s.

Two late Victorian works anticipate later developments. Edward Dowden's sensitive

Shakspere: A Critical Study of his Mind and Art

( 1875) in part looks into the plays for the writer's 'personality'

and 'the growth of his intellect and character', but, oddly, neglects

the theatre itself. A major biography, Sidney Lee

A Life of William Shakespeare

( 1898), issued in revised versions until 1925, concerns the plays as

well as the life; I find the book full, specific, and readable. Yet

its commentary is literal or philistine in quality, and, worse, Lee

offers suppositions as facts. Guesses become truths. He claims for

example that the poet collaborated with Marlowe, and factually errs in

his comments on dramas, taxes, and the poet's income. With simpler

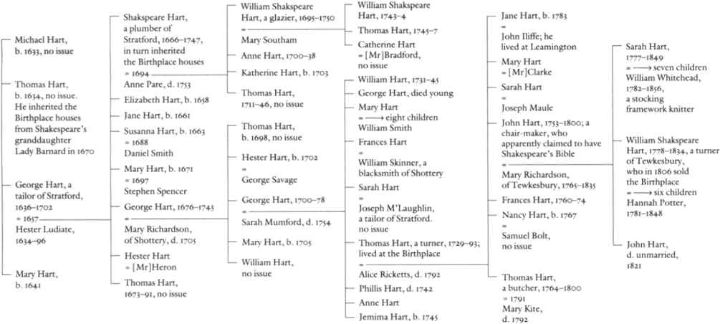

matters, as in a chapter entitled 'Survivors and Descendants' (in its

full 1925 version) Lee is useful, but his work is mainly as badly

dated as Joseph Quincy Adams's bland but not eccentric

Life of William Shakespeare

( 1923).

Twentieth-century biographers have benefited from the work of their

predecessors, and also from a tradition in criticism which has

enlisted leading writers in every age since the poet's death. One thinks

of remarks upon Shakespeare by Ben Jonson and Milton who were alive

in his time, or by Dryden, Pope, Dr Johnson, and Boswell, or in

-418-