Sharing Is Good: How to Save Money, Time and Resources Through Collaborative Consumption (7 page)

Read Sharing Is Good: How to Save Money, Time and Resources Through Collaborative Consumption Online

Authors: Beth Buczynski

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Consumer Behavior, #Social Science, #Popular Culture, #Environmental Economics

on connections between one or more individuals, even if those in-

dividuals never actually meet face-to-face (although that does make it easier). If you live in densely populated places like New York City or San Francisco, it’s pretty easy to find a community in which you feel comfortable. These are massive metropolises, full of millions of people with different likes, dislikes, passions, and beliefs. Although all those people add up to lots of extra traffic and high apartment prices, they also make some things easier.

Why We Don’t Share

27

Big cities have lots of different types of people living close to one another (experts call this

urban density

) which makes it more likely that a new idea or business endeavor will succeed if people like it.

Why? Because there are more people living relatively close to the place where a group, start-up, or business exists. If you don’t believe me, try this: Go to Craigslist for the San Francisco Bay area and click on the “Activities” column. You’ll find at least 50 new listings per day, more if it’s the weekend. Go to the same column for the

entire state of Wyoming, and you’ll be lucky to see one listing in a whole week. Why such a big difference? Easy, there are lots of people in San Francisco, all living in a small geographical area. Wyoming is big geographically, but its entire population could fit inside San Francisco, with lots of room to spare. In Wyoming, towns and people are extremely spread out, but in San Francisco, they’re all on top of each other. Sociological research shows that density is a key component of creativity, innovation, and knowledge sharing. In short, the more people there are living close together, the more likely something awesome is going to happen.7

Urban density compels collaborative consumption companies to

launch in big cities where they have the best chance of reaching the most people. Not only are sharing concepts more likely to be popular in cities where space and resources are at a premium, it’s also likely that the innovative, creative minds that tend to congregate in cities will be more open to the idea in the first place. This isn’t to say that urban populations have a monopoly on innovation or collaboration, because they don’t. Many world-changing ideas have come from people who live in small or rural towns. It’s just that urban cultures are usually more diverse and willing to dabble in the new and uncharted.

Experimentation occurs in the less dense towns as well, it’s just hard to bring it to critical mass so that it becomes the norm instead of a freak-show. You may have an awesome idea for how your community can

share a thing or service, but unless you’ve got a bunch of other people willing to try, it’s going to be hard to prove your idea is a good one.

28

Sharing is Good

This natural gravitation of sharing endeavors toward heavily

populated areas leaves the rest of us to muddle through until the service we want reaches our town. And even for those who live in urban areas, swap meets, co-ops, and transportation sharing alternatives can still be hard to find or too far away to be useful. The good news is that the global community provided by online sharing forums can substitute for a local community until your friends and neighbors are ready to give it a try.

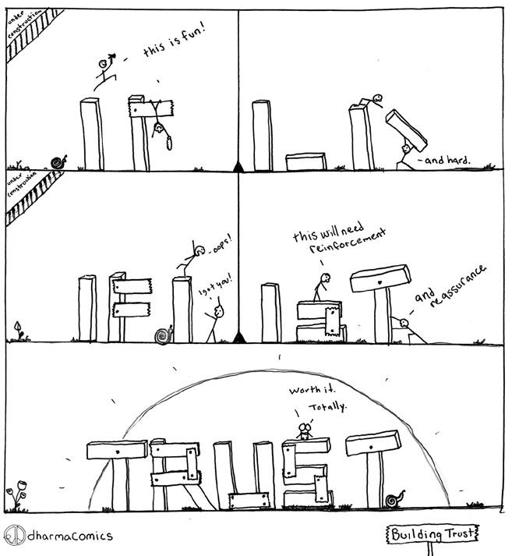

Trust

It might be a little cynical, but most of us just don’t like the idea of other people touching our stuff. If you’ve ever lent something to a friend only to have it returned broken or just outright stolen, you can identify with this concern. And it works the other way around too: how can you be sure that the person lending out their apartment has been truthful about its cleanliness or the quality of the neighborhood? If you’ve been hoarding these fears about participating in the sharing economy, take some comfort in the fact that you’re not alone.

A 2012 study conducted by marketing agency Campbell Mithun

found that 67 percent of those surveyed expressed trust concerns

as the primary barrier to joining a collaborative consumption service.8 When pressed to explain what they feared would happen if

they started sharing, 30 percent said they were afraid that their goods would be stolen or broken, 23 percent cited a basic mistrust of strangers, and 14 percent expressed “privacy concerns.” These are what social scientists like to call

perceived risks.

They’re based on perceptions that may or may not be borne out in real life. Fear of flying is another good example of perceived risk. Lots of people are afraid their plane will crash to the ground mid-flight, even though, statistically, it’s far more dangerous to travel by car.

We could spend a lot of time talking about where these percep-

tions of risk come from (the media, over-protective parents, a bad experience, etc.), but where they come from isn’t really as important

Why We Don’t Share

29

as finding a way to deal with them. Caution is good. Crippling trust issues that prevent you from interacting with your community are

bad. The best way to deal with a lack of trust is to be trustworthy yourself. We can only expect from others what we’re willing to do ourselves. Also, a little pre-planning can go a long way. It’s necessary to be upfront and honest about what could go wrong in a sharing

situation, whether it’s with your neighbors or someone in another country. More about this later.

So, do you still think it’s impossible for you to dip your toe into the sharing economy? Still think sharing sounds like a nice idea, 30

Sharing is Good

but you’ll have to a) be less busy, b) research it more, c) have more money, or d) wait until it comes to your town in order to give it a try? It’s possible that you have other reasons for not sharing, but hopefully, this chapter has helped you see that no barrier to sharing is impenetrable.

Chapter 3

Why Share Now?

Sharing has come in handy for hundreds of years in the

form of public libraries, cooperatives, and more recently, services like eBay or Netflix. So why is it so important to start sharing now or to branch out into new forms of sharing in different areas of your life? To answer those questions, let’s take a look at how civilization has changed over the last couple centuries. From this bird’s eye view, we see that there are more of us than ever before (and the population is growing exponentially), we’re consuming more than ever before

(and it’s not proportionate to population growth), and the waste

from this excessive consumption has nowhere to go (and as a result, it’s poisoning our planet). We also see that the recent technology boom that put laptops and smartphones into millions of pockets

presents a unique opportunity for community building on an un-

precedented scale.

There Are More of Us Than Ever Before

In October 2011, the world global population reached 7 billion

people. According to United Nations demographers, it’s likely that 31

32

Sharing is Good

the seven billionth person was born in India, the country with the highest per minute birth rate in the world. Population growth hasn’t always been exponential like this. If you were to observe a chart of human population growth over time, you would see a “J” shape. The most obvious increases in population coincide with drastic changes in the physical or cultural environment. Cultural revolutions, such as the Agricultural or Industrial Revolutions, have led to surges in population growth more often than physical changes, like drought or famine, have lead to population reduction. Even the World Wars and the bubonic plague, which wiped out millions, are barely perceptible dips in overall population growth. Slow but steady growth continued through the 20th century, but that’s where the graph goes wild.

In the 1950’s, the world was just starting to recover from WWII.

The world’s population stood at a mere 2.5 billion. People in indus-trialized nations were happy for the first time in years, felt relatively safe, and thanks to the military-industrial complex, there was a surplus of consumer goods available to help them achieve the “good life.”

The crude birth rate (number of births per 1,000 people per year) from 1950–1955 was 37.2, and the global population doubled in a

quick 40 years. Compare that to the crude birth rate of 21.2 from 2000–2005, and our current accelerated population growth doesn’t

seem possible. If fewer people are being born per year, where is all this extra population growth coming from? Improvements in healthcare and medicine along with exploding populations in developing

countries mean more people are simply staying alive longer.

Living a long, healthy life doesn’t seem like such a bad thing, so why is population growth cause for alarm? Well, according to the

UN, about half of the 7 billion people alive today live in poverty, and at least one fifth are severely undernourished.

Most new humans will spend their lives pursuing the fruit of

“inalienable rights” that those lucky enough to be born in wealthy countries take for granted. Unfortunately, people in developing nations often strive to emulate the Western world’s method of fulfilling Why Share Now?

33

their rights: getting stuff, money, and more stuff. This makes population growth an even worse problem.

The planet doesn’t have enough water, energy, or minerals to pro-

vide 10 billion human beings with an iPhone (much less a new one

every year). The planet isn’t capable of supplying 10 billion human beings with enough wood, stone, or space to inhabit their own

McMansion. In short, planet Earth is not capable of sustaining a

population of 10 billion people in the manner to which the Western world has grown accustomed. What happens when we run out of

not only iPhones, but also food, potable water, and fossil fuels? If human beings can’t get along now, when most of us have access to

what we need to survive, something tells me that extreme resource shortages aren’t going to bring out the best in us. This is why the current rate of population growth is a compelling reason to share now, rather than later. This is why it’s so important for us to shift our focus away from our

me, me, me/take, take, take

culture. Maybe the individualistic, capitalistic mentality that dominates the world’s major economies isn’t the best example to follow. Maybe there is a better way. Maybe a resurgence of resource sharing, instead of divid-ing, is the start of that better way.

We’re Consuming More Than Ever Before

In the past three decades alone, human beings have consumed one-

third of the planet’s natural resources base.9 In its 2004 “Living Planet Report,” the World Wide Fund for Nature said humans currently consume 20 percent more natural resources than the Earth can replenish. Considering that consuming even 1 percent more than the Earth can produce would be problematic, this fact alone represents a crisis.

Consumerism has permeated every aspect of our lives, includ-

ing how we talk about ourselves. We’re not just human beings or

people any more, we’re consumers. Have you ever noticed how the

media uses that word interchangeably with “person,” “individual,” and 34

Sharing is Good

“family”? Some of the things we consume have always been neces-

sary for existence — food, water, oxygen. But most of the things we consume have only been around for a few decades, and they are completely extraneous to our survival on this planet. We’ve got houses, garages, and storage lockers full of stuff that we “needed” at one time or another. Many of these things only see minutes of use, if that, throughout our entire lifetime, yet we can’t let them go. In recent history, human consumption of natural resources has exploded, and it’s not proportional to population growth. Although the US birth rate is one of the lowest in the world, it consumes a huge portion of the world’s resources.

A few examples:

• The United States, with less than 5 percent of the global population, uses about a quarter of the world’s fossil fuel resources —