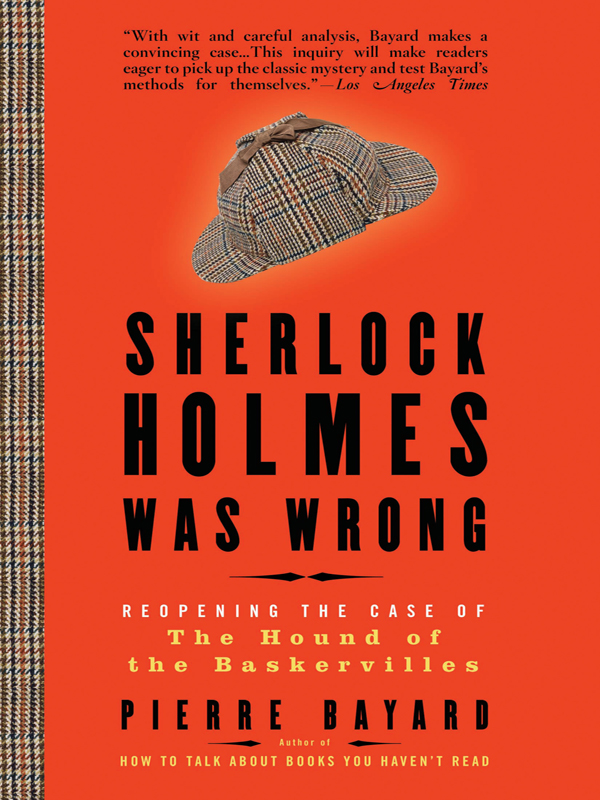

Sherlock Holmes Was Wrong

Read Sherlock Holmes Was Wrong Online

Authors: Pierre Bayard

Sherlock Holmes

Was Wrong

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read

Sherlock Holmes

Was Wrong

Reopening the Case of

The Hound of the Baskervilles

PIERRE BAYARD

Translated from the French

by Charlotte Mandell

Copyright © 2008 Les Editions de Minuit

English translation copyright © 2008 by Charlotte Mandell

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from

the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

For information address Bloomsbury USA,

175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

All papers used by Bloomsbury USA are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing

processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Bayard, Pierre, 1954–

[L’affaire du chien des Baskerville. English]

Sherlock Holmes was wrong: reopening the case of the

Hound of the Baskervilles / Pierre Bayard; translated

from the French by Charlotte Mandell.—1st U.S. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-1-60819-244-1

1. Doyle, Arthur Conan, Sir, 1859–1930. Hound of the Baskervilles.

I. Mandell, Charlotte. II. Title.

PR4622.H63B3913 2008

823'.912—dc22

2008032807

First published in the United States by Bloomsbury USA in 2008

This paperback edition published in 2009

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Westchester Book Group

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

For Guillaume

The barriers between reality and fiction are softer than we think; a bit like a frozen lake. Hundreds of people can walk across

it, but then one evening a thin spot develops and someone falls through; the hole is frozen over by the following morning.

JASPER FFORDE,

The Eyre Affair

Contents

The Devonshire Moors: Dartmoor

IV. The Principle of Incompleteness

I. What Is Detective Criticism?

I. Does Sherlock Holmes Exist?

II. The Immigrants to the Text

Sherlock Holmes:

English detective. Believed to be dead after his disappearance in the Reichenbach Falls, in Switzerland, he is resurrected

by Conan Doyle, eight years later, in

The Hound of the Baskervilles

.

Dr. Watson:

friend and colleague of the detective.

Sir Charles Baskerville:

owner of the manor house that bears his name. Dies under mysterious circumstances just before the beginning of the novel.

Henry Baskerville:

nephew of Charles Baskerville, heir to his uncle’s manor house and fortune.

Dr. James Mortimer:

friend of the Baskervilles. Travels to London at the beginning of the novel to ask Sherlock Holmes to investigate Sir Charles

Baskerville’s death; he thinks the police brought their investigation to a close too quickly.

Jack Stapleton:

naturalist living near Baskerville Hall. Sherlock Holmes discovers that he belongs to the Baskerville family and suspects

him of being Charles’s murderer.

Beryl Stapleton:

wife of Jack Stapleton. He passes her off as his sister.

John Barrymore:

butler in Baskerville Hall.

Eliza Barrymore:

wife of John Barrymore and sister of Selden.

Selden:

escaped convict, brother of Eliza Barrymore.

Frankland:

bitter old man who lives on the moor and constantly sues his neighbors. Father of Laura Lyons, from whom he is estranged.

Laura Lyons:

daughter of Frankland and mistress of Staple-ton. Lives alone on the moor.

The hound:

watchdog. Accused by Sherlock Holmes of two murders and one attempted murder.

FROM THE CHAMBER where she has been locked for hours, the young woman hears shouts and laughter rising from the great dining

hall below. As the evening advances and talk becomes more heated under the influence of alcohol, her anxiety mounts at the

thought of the fate intended for her by the men she can hear carousing below. First among them, worst of them all, is the

leader of the gang, Hugo Baskerville, corrupt owner of the manor house that bears his name.

For months Hugo had been hovering around the young country lass, whom he had tried to attract by every possible means, first

by trying to seduce her, then by offering her father large sums of money if he would agree to further their relationship.

But she found him vile, repulsive; she kept avoiding him. So Hugo and his men, on this Michaelmas, have resorted to violence.

While the girl’s father and brothers have been away, the have kidnapped her and brought her to Baskerville Hall.

When the bedroom door had first closed behind her, the girl had stayed motionless for a while, paralyzed by emotion. Now,

overcoming her fear, she comes to herself and begins looking for a way to escape. First she tries to force the lock, but she

soon abandons the idea. Made of metal and set into a massive oak door, it would be impervious to her blows.

A quick look around the room reveals that aside from an inaccessible chimney flue there is only one available opening: a little

window, just large enough for a slender person to climb through. But leaning out, she sees that the ground is far below; jumping

would mean breaking a limb, even killing herself.

But this opening is the only one that lets the prisoner entertain a faint hope—provided she can show some nimbleness, and

is willing to risk her life on one stroke of luck. There is ivy climbing the front of the house from the ground to the roof,

and so she resolves, daring everything, to stretch out her arm, grab hold of it, and begin a perilous descent.

Having finally reached the ground, the young woman ignores her scratches and at once starts running away from the Hall and

toward her father’s house, whose lights three leagues across the moor she can more intuit than glimpse.

Despite her pain and anguish, her hope begins to rekindle as she gets farther from her prison. She fights off the terror of

the darkness and the eerie noises from the moor, a world inhabited by supernatural creatures, in this era not yet civilized

by science.

These indistinct noises are soon dominated by a stronger, more regular sound approaching quickly. The origin is easy to recognize.

It is a horse galloping along the path at top speed, urged on with shouts by its rider, and there can be no doubt about its

target.

But whoever attentively lends his ear to the sounds of the moor will hear even worse. More terrifying than the noise of galloping

hooves is the howling of a pack of dogs, the barking closer and closer, as if they were outrunning the horse and had already

left it far behind.

The young woman realizes now that her jailer has found her missing and is in hot pursuit. But he wasn’t content to ride after

her. He also set the pack of hounds that he uses for hunting on her trail, probably after having them sniff a piece of clothing

of the prisoner who is now their quarry.

Dropping from fatigue, dying of fright, the young woman has no choice but to abandon the path and hurl herself into a broad

ravine, a

goyal

, marked long ago by the inhabitants of the place with two tall stones. She knows she has no chance of escaping her kidnapper;

all she can do is gain a few minutes’ respite before she is discovered and torn apart by the hounds.

Crouching low to the ground and trying to catch her breath, she waits for the inevitable end, making her last resigned prayers.

The end is not long in coming. Hugo Baskerville jumps down from his horse, not even taking the time to tie it to a tree, and

bounds into the goyal.

But the pursuer does not look like the formidable man she was fearfully expecting to see leap from the shadows. His face is

deformed not with the fury of the hunter who has allowed his prey to escape, but with a nameless terror. Hugo Baskerville,

like his victim, is now reduced to the status of prey.

Behind him rises up the monstrous form of a giant black dog, so huge it defies imagining. With its bloodshot eyes, it seems

to have come straight out of hell to the edge of the goyal. With a giant leap, it hurls itself onto Hugo, who rolls on the

ground, shouting with horror. His shout is stifled in his throat at once as the monster sets his fangs into it, and the young

man quickly loses consciousness.

Stunned by the sight, her nerves spent, the young woman collapses and dies of exhaustion and fear, so that when Hugo’s companions

reach the edge of the goyal there are two corpses for them to discover. So shocking is the spectacle that some of them—it

would be said in the neighboring villages—die of fear and others go mad ever after.

What is the girl thinking about as she is dying? Although the texts that have come down to us remain silent on this point,

we are not forbidden to use our imaginations. The thoughts of characters in literature are not forever locked up inside their

creators. More alive than many living people, these characters spread themselves through those who read their authors’ work,

they impregnate the books that tell their tales, they cross centuries in search of a benevolent listener.

This is true for the young woman whose final moments at the bottom of a goyal on the Devonshire moor I have just related.

Her last thoughts carry an encoded message, a message without which Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s most famous work remains incomprehensible.

It is to reconstruct these thoughts and their secret effects on the plot that this book has been undertaken—for this, and

for the dead girl’s memory.

To understand what she had to tell us, I have taken up in minute detail an investigation into the murders blamed on the Hound

of the Baskervilles. In so doing, I have made a number of discoveries that, piece by piece, go far to cast doubt on the official

verdict. After examining a series of convergent clues, I feel there is every reason to suppose that the generally acknowledged

solution of the atrocious crimes that bloodied the Devonshire moors simply does not hold up, and that the real murderer escaped

justice.

How could Conan Doyle be so mistaken about this? Faced with such a complex enigma, he probably lacked the tools of contemporary

thought on the topic of literary characters. These characters are not, as we too often believe, creatures who exist only on

paper, but living beings who lead an autonomous existence—sometimes going so far as to commit murders unbeknownst to the author.

Failing to grasp his characters’ independence, Conan Doyle did not realize that one of them had entirely escaped his control

and was amusing himself by misleading his detective.

By undertaking a theoretical reflection on the nature of literary characters, their unsuspected abilities, and the rights

they are entitled to claim, this book intends to reopen the file of

The Hound of the Baskervilles

and finally to solve Sherlock Holmes’s incomplete investigation—and in so doing, to allow the young girl who died on bleak

Dartmoor and has wandered for centuries since in one of those in-between worlds that surround literature, to find her rest

at last.

*

* All my thanks to François Hoff, eminent Sherlock Holmes specialist, for reading this manuscript so carefully and for giving

me some useful suggestions.