Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life (68 page)

Read Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life Online

Authors: Ruth Franklin

Tags: #Literary, #Women, #Biography & Autobiography

i am writing about ambivalence but it is an ambivalence of the spirit, or the mind, not the sex. . . . it is fear itself, fear of self, that i am writing about, fear and guilt and their destruction of identity, and any means at hand will do to express them; why am

i

so afraid?... i am frightened by a word. . . . but i have always loved (and there is the opposition: love) to use fear, to take it

and comprehend it and make it work and consolidate a situation where i was afraid and take it whole and work from there. so there goes

castle

. i can not and will not work from within the situation; i must take it as given. . . . i delight in what i fear. then

castle

is not about two women murdering a man. it is about my being afraid and afraid to say so, so much afraid that a name in a book can turn me inside out.

The fear Jackson refers to is not fear of lesbianism—or, at least, not only fear of lesbianism. It is the fear of what lesbianism represented to her, something that on one level she fervently desired even as she feared it: a life undefined by marriage, on her own terms. Constance and Merricat are indeed “two halves of the same person,” together forming one identity, just as a man and a woman are traditionally supposed to do in marriage. Not finding that wholeness in marriage, Jackson sought it elsewhere: first with Jeanne Beatty, and later with her friend Barbara Karmiller, also younger, who came back into her life shortly after she finished

Castle

. Indeed, the novel, in its final version, is not about “two women murdering a man.” It is about two women who metaphorically murder male society and its expectations for them by insisting on living separate from it, governed only by themselves.

“

FOUR PEOPLE HAVE READ

the first two chapters . . . and all independently announce that it is the best work i have ever done. . . . i finally got it into a kind of sustained taut style full of images and all kinds [of] double meanings and i can manage about three pages a day before my eyes cross and my teeth start to chatter,” Jackson wrote to Jeanne Beatty as the novel began to take shape. “Sustained taut style” is an apt description of this allusive, hypnotic book, which, at only 214 pages, is the briefest of her novels. In draft after draft, she mercilessly stripped out extraneous backstory, dialogue, and exposition. The final version is as economical and evocative as “The Lottery”: on one level absolutely straightforward, but with a network of hidden meanings stretching like roots beneath the surface.

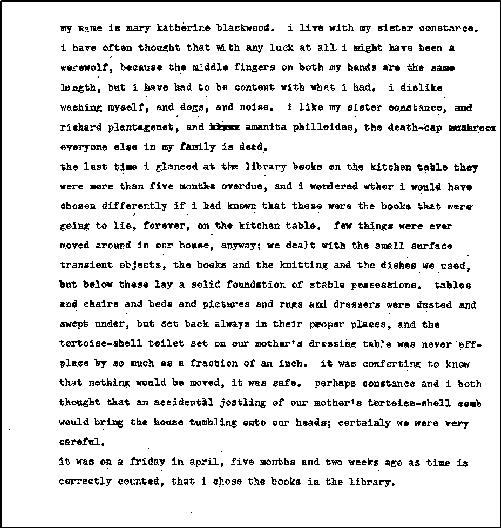

The first page of a draft of Jackson’s manuscript for

We Have Always Lived in the Castle.

Castle

is told entirely from the perspective of Mary Katherine Blackwood (Merricat, as her sister calls her), Jackson’s most ambiguous heroine. Eighteen years old, she lives with her sister, Constance, and their uncle, Julian, an invalid, in their longtime family mansion. The rest of the Blackwoods are dead, poisoned six years earlier at the dinner table by someone who put arsenic in the sugar that the family members used to sweeten the blackberries served for dessert on the fateful night. The novel teasingly withholds confirmation that Merricat was the murderer, but there can be no real question in the reader’s mind. She chose the poison deliberately to spare Constance (who does not use sugar on her berries), ten years older, whom she adores: “She was the most precious

person in my world, always.” Protective of her little sister, Constance took the blame, washing out the sugar bowl immediately to hide the evidence, and stood trial. Even though—or perhaps because—she was acquitted (for reasons that are never made clear), the residents of the village ostracize the family.

Like the house in

The Sundial

, the Blackwood mansion sits physically at a remove from the village beneath it, surrounded by a barrier—in this case a fence put up by Merricat and Constance’s father. When Merricat goes into town to do errands a few days each week—Constance never goes past the garden—the townspeople stare at her and children chant rude rhymes. “Merricat, said Connie, would you like a cup of tea? Oh no, said Merricat, you’ll poison me.” Other than those brief excursions, the two women are entirely self-sufficient. Constance does all the cooking and gardening because Merricat, according to their personal system of household rules, is not allowed to handle food, but together they take satisfaction in “neatening the house,” preserving its order exactly as their parents left it. “We always put things back where they belong,” Merricat explains. “We dusted and swept under tables and chairs and beds and pictures and rugs and lamps, but we left them where they were; the tortoiseshell toilet set on our mother’s dressing table was never off place by so much as a fraction of an inch. Blackwoods had always lived in our house, and kept their things in order; as soon as a new Blackwood wife moved in, a place was found for her belongings, and so our house was built up with layers of Blackwood property weighting it, and keeping it steady against the world.”

The women’s domestic security is disrupted by the arrival of their cousin Charles, who appears to take a romantic interest in Constance but is more interested in assuming control of the estate and, thus, the family money hidden within it. Merricat, jealous and fearful at losing Constance and their way of life, plays pranks on Charles and finally, though perhaps accidentally, sets the house on fire. (She puts Charles’s still burning pipe in a wastebasket full of newspapers, but it’s not entirely clear that she grasps the almost certain consequences of this act.) The fire department, led by a village man who takes particular pleasure in tormenting Merricat, puts it out in time to spare the first floor. But then

the fire chief, deliberately removing the hat that marks him as an official, leads the villagers in a violent rampage. While the sisters hide in the garden, their neighbors (with shades of “The Lottery”) throw stones through the windows, smash heirloom china and furniture, and destroy Constance’s harp, which falls to the floor “with a musical cry.” Charles, whose voice is heard several times urging the firemen to rescue the safe in which the sisters keep their money, does not defend his cousins or otherwise intervene. After the disaster, it becomes clear that the fire served as a kind of purification ritual by which the villagers were at last able to make peace with the Blackwoods. The sisters set up house with their surviving furniture and cookware in the shell that remains, and now their neighbors, instead of pointing and jeering, stop by periodically to leave offerings of food on the doorstep. “We are going to be very happy,” Merricat repeats to Constance.

As always while she was writing, Jackson paid careful attention to the physical space in which the novel takes place, drawing a map of the village depicting the shops, the main roads, and the path leading to the Blackwood house. The village, as described in the novel, sounds very much like North Bennington, with wealthier homes on the outskirts and a main street where all the villagers mix; in Jackson’s sketch, the similarities are even more obvious. Some of Jackson’s friends would later say she told them that Merricat’s experiences in the village were based on her own. “We knew we were different,” says Joanne Hyman. “Our parents were Democrats, we were atheists. We didn’t fit in. We were . . . not paranoid, but a little bit self-conscious.” Jackson also made diagrams of the dining room table, showing where each family member sat on that fateful last night, and her children remember her asking them to reenact the scene at the Hymans’ oval dining table, with each of them representing a member of the Blackwood family.

While the novel’s geography is carefully defined, motives are left uncertain, although the careful reader will notice hints. Why do the villagers despise the Blackwoods? What happened to Constance in town that made her decide never to venture beyond the garden? Why is Uncle Julian fixated on the night of the murder, obsessively recording every detail that he can remember? And, most crucially, what drove Merricat

to murder most of her family? Early drafts give explicit answers to all these questions: regarding the murder, their mother treated Constance like Cinderella, forcing her to cook and clean in drudgery. In the final version, a single crack in Constance’s docility is seen when, on the night of the murders, she tells the police that “those people deserved to die”—but she could be covering for Merricat. In another ambiguity, she also is the only of the sisters who expresses regret over the loss of the family, remarking once that she would “give anything to have them back again.”

In

Hill House

, Jackson left the novel’s most frightening elements unspoken, beneath the surface. She uses the same technique in

Castle

, but takes it to an extreme:

everything

is left mysterious. In contrast to the maximalist prose that characterizes the work of Kerouac or Bellow—Kerouac’s

Big Sur

appeared in 1962, the same year as

Castle

; Bellow’s

Herzog

came two years later—Jackson reduces episodes that could have been entire scenes to a single sentence. Isaac Bashevis Singer—the “Yiddish Hawthorne,” Hyman called him in a review—complimented Jackson on

Castle

’s mysteriousness, which he found “European in spirit.” “Where is it written that a writer must explain everything?” he wrote to her. “I am, like you, against too much motivation. The less[,] the better.” In early versions, Constance and Charles engage in fantasies about their future together; in the final, their plans are only alluded to. Merricat’s thinking as she starts the fire also was elaborated in the draft version: “there were newspapers in the wastebasket and his pipe, burning, on the table. it was a good omen, although i already knew that he put his pipe down all the time and forgot it. all i had to do was brush the pipe and ashtray off the table and into the wastebasket. sometimes things like that turn out all right and sometimes they turn out all wrong.” In the final version, she simply sweeps the pipe into the wastebasket, with no further comment.

The most crucial revision Jackson made between the drafts was her shaping of Merricat’s character, which is so crucial to the book in its final form that Jackson’s own shorthand for the novel was “Merricat.” The “Jenny” figure, as Jackson described in her unsent letter, is “absolutely secure in her home and her place in the world”; Constance is the

one who is uncertain, who needs protecting. At an intermediate stage of the manuscript, an older version of Merricat, who returns home from an unspecified job in the city to take care of Constance, is still presented as the adult in the family. By the final draft, their positions are entirely reversed. Constance, as her name suggests, is the embodiment of peace and stability, angelic with her blond hair and rosy skin, even her harp. Merricat is untame, uncontrollable, her world governed by superstition rather than reason. Like a witch or a devil, she is accompanied everywhere by her black cat, and believes that she keeps herself and Constance safe through her magic rituals. Her peculiarities are evident from the book’s iconic first paragraph, as astonishing as the opening to

Hill House

:

My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and

Amanita phalloides

, the death-cup mushroom. Everyone else in my family is dead.

In her “Garlic in Fiction” lecture, Jackson described her technique of zeroing in on a few specific words that take on a special significance in the context of each novel. Merricat’s symbolic words, “safe” and “clean,” pinpoint her singular focus: keeping the private world of the Blackwood estate free from intruders and perfectly in order (according to her own irrational logic). Her reliance on magical thinking makes her seem younger than she actually is; perhaps the reader is meant to think that, like the Betsy persona in

The Bird’s Nest

, her development was arrested at a traumatic moment—in this case, the murder. While shopping in town, Merricat distracts herself by pretending that the sidewalk is a board game with squares for “Lose a turn” (if she has a difficult encounter) or “Advance three spaces” (if all goes smoothly). She stashes objects around the property to form “a powerful taut web which

never loosened, but held fast to guard us”: silver dollars by the creek, a doll buried in a field, a book nailed to a tree. “All our land was enriched with my treasures buried in it.” She chooses magic words that will retain their protective force only as long as they are never spoken. After her magic fails and Charles gains access to the sanctum, she becomes obsessed with removing any traces of him. (This is why Jackson uses the word “neaten” to describe the sisters’ regular housekeeping rather than the more usual “clean”; in

Castle

, the purpose of cleaning is to remove spiritual contamination.) The fire is the ultimate cleaning agent that will finally achieve Merricat’s desired result: to erase Charles’s presence from the house entirely.