Read Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher (9 page)

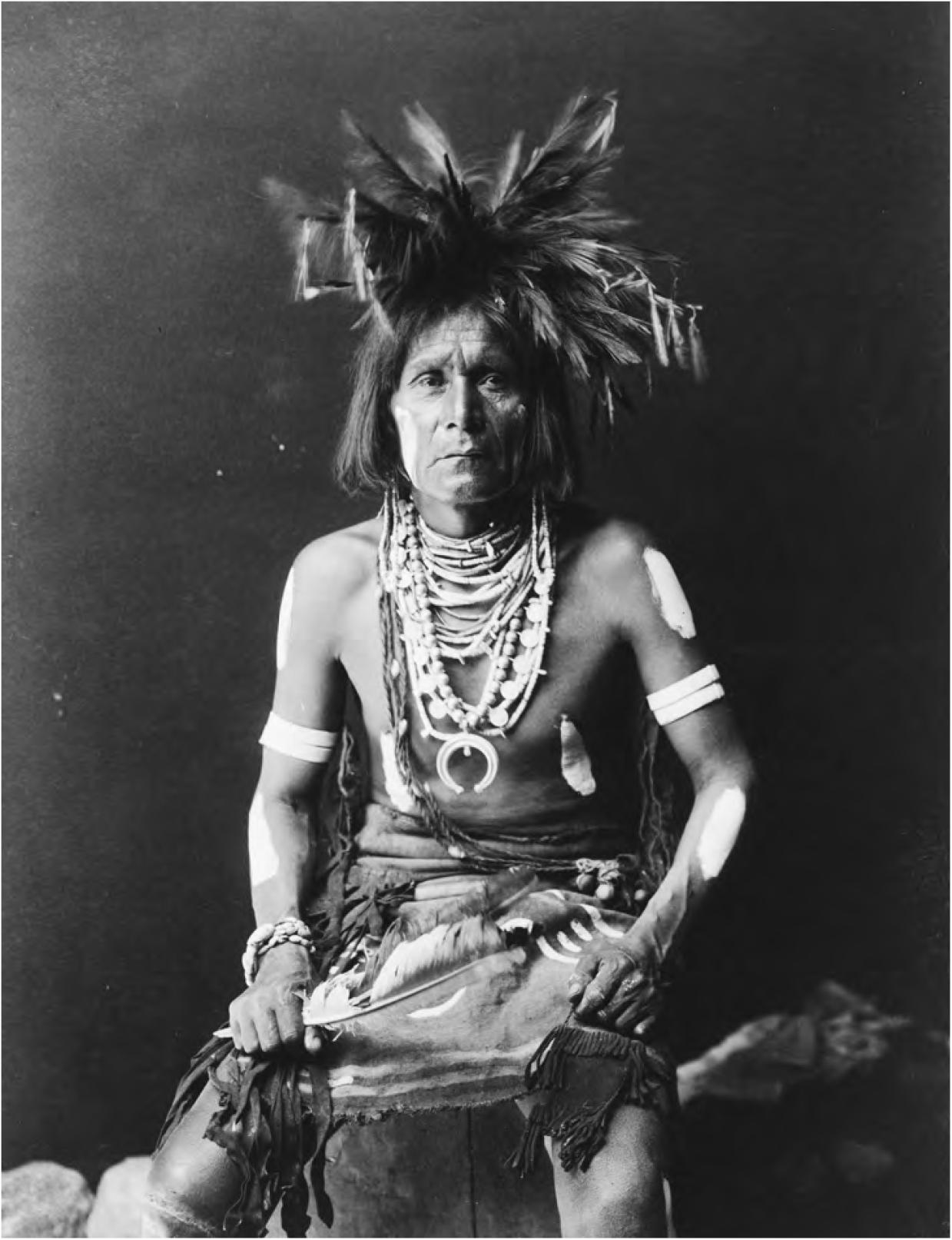

America was stitching itself ever tighter, through rail lines and roads for automobiles;

by decade’s end, airplanes would fly with the birds in every part of the country.

At the same time, the Indians who wished to continue living the old ways had to take

refuge—to hide, essentially—from the dominant culture. The populous Navajo were spread

throughout the north of Arizona Territory, over the border into the sandstone wilderness

of Utah, down along parts of New Mexico. The Havasupai, a tiny band, lived literally

out of sight: in a deep hole at the western edge of the Grand Canyon, thousands of

feet into a slit carved by runoff into the Colorado River. The Mojave were farther

south, their lives blended with some of the harshest desert of the world. To find

the longtime nomadic Apache, Curtis would have to go high into the mountains and deep

into pine forests. He would have to follow the Rio Grande above Santa Fe to encounter

Pueblo people who had been conquered by the Spanish three hundred years earlier. All

of this was just in the Southwest. If Curtis was going to do something definitive,

exhaustive and encyclopedic, he would also have to spend much time on the plains,

in the Rockies, in the fjords of British Columbia and Washington State, in the northern

California mountains and the southern California desert, in the Arctic.

Curtis was confident he could do it all. He may not have had money or education, but

he had robust health, he boasted—he felt strong, always full of zip, plowing through

sixteen-hour days, seven days a week. Only on rare occasions in the first years did

he express any doubt, and then as a way to solicit further encouragement. How many

tribes would he have to visit to cover the full scope of native peoples living as

they had before Anglo dominance? Twenty? Forty? Sixty?

“I want to make them live forever,” he told Grinnell. “It’s such a big dream I can’t

see it all.”

The tribes may have been numerous, but the overall population was plummeting. When

the results of the 1900 census were published, the government counted only 237,000

Indians in a country of 76 million people. This was the lowest number ever, scholars

and Indian authorities said, down from perhaps as many as 10 million at the time of

white contact in 1492. Typhus, measles, bubonic plague, influenza, alcohol poisoning,

cholera, tuberculosis—the diseases introduced to the New World from the Old rolled

across the big land and through the centuries, wiping out nations along the way. If

these trends continued, in the consensus view of government policymakers, American

Indians could vanish within Curtis’s lifetime. Perhaps he was already too late.

1900. The closeness of Edward Curtis to his subjects made for a productive season

at the Blackfeet reservation in Montana. That summer changed Curtis’s life, launching

his photographic epic.

1900. This was the first time Curtis had seen an entire Indian community, intact

and vibrant. He was enthralled.

, 1900. After his first visit with the Hopi in Arizona, Curtis vowed to become a part

of the Snake Priest society.

1903

A

FEW MINUTES BEFORE

kickoff at the biggest football game of the year in Seattle, the crowd in the splintered

wooden stands craned to get a look at an entourage leading a tall, full-haired dignitary

to the sidelines. Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce was with his nephew Red Thunder, trailed

by a knot of newsmen. He was known worldwide as the Indian Napoleon, a field genius

who had outwitted the American cavalry and some of its best generals in a 1,700-mile

retreat from his homeland in northeast Oregon to the Canadian border. The Nez Perce

War of 1877 had made Joseph—a striking-looking man whose native name,

Hin-mah-too-yah-la-kekt,

or Thunder Rolling Down the Mountains, carried power and music in six syllables—a

household figure in Europe and the United States. As the last of the great chiefs

died, and the Indian world seemed an ever more distant era, Joseph’s fame grew. Only

Geronimo, the aging Apache warrior, was as well known.

“Rah, rah, rah!” The spectators at Athletic Field took up a chant, and one of Joseph’s

escorts said they were cheering in his honor. Turn and wave, he was told—they want

to see you! The new boots on his feet were muddied by the stone-and-clay gumbo of

the field, and the wind bit at his face. A thick woolen blanket was wrapped around

his shoulders. It was late November, the darkest, wettest, bleakest time of the year,

days when the sun might not be seen for weeks and the light would flee in midafternoon.

“The most noted Indian now living,” as the papers put it, was in Seattle at the invitation

of the Washington Historical Society. What better exhibition could they put on? A

famous Indian! An exotic from the past! See him and hear him and touch him while he’s

still alive! He was allowed to leave the virtual prison of his plot of reservation

ground on the Columbia River Plateau, to cross the mountains and come to speak as

the society’s guest. Joseph had accepted the offer, not because he liked being on

display, but because he hoped to persuade influential people to take up his cause.

Not since Teddy Roosevelt came to town a few months earlier had Seattle been so stirred

by a visitor. The president gave a speech before fifty thousand people, urging citizens

of the Northwest to conserve their salmon and forests. A big news story on the Sunday

before Joseph’s arrival included pictures of the chief on his latest trip to Washington,

D.C., there to “plead with the Great Father for the return of the Wallowa Valley,

the home of his fathers.” He had met with Roosevelt on the visit, to little avail;

the Nez Perce leader was poor, aging and without any leverage but his renown. That

celebrity had given him access, if not influence, during his extensive travels over

the past five years. In the spring of 1900, he’d met President William McKinley. While

on the East Coast that year, he was very much in demand. Would he come to New York

for the dedication of General Grant’s tomb? No, the chief said, he couldn’t afford

it. Well then, Buffalo Bill Cody offered to pay his way and put Joseph up at the Astor

House with him, which did more for the consummate showman than it did for the single-minded

cause of the Nez Perce chief. In Manhattan, Joseph walked around town one day in a

full war bonnet, at the prompting of Cody; the rest of the time he wore a suit jacket.

“Did you ever scalp anyone?” a woman asked him in New York. Joseph didn’t speak English.

But using a translator, he tried to convey a single message: the once mighty Nez Perce,

beloved and celebrated by Lewis and Clark and expeditions that followed, known for

their horsemanship, their good looks and manners, their prosperous villages spreading

over three states, were in crisis. The Joseph band, which had never converted to Christianity

and refused to acknowledge a clearly fraudulent rewrite of a treaty, had dwindled

to 127 people. The war of 1877 had ended badly for the bedraggled tribe, an assemblage

of elders, women, children, babies and very few warriors. They had eluded about two

thousand American soldiers in a chase that took them to the depths of Hells Canyon,

over the most rugged mountains of Idaho and into Yellowstone National Park, north

through Montana to the Canadian border, where they would have been safe had they been

able to cross over. Along the way, small groups of Nez Perce had twice surprised and

attacked much larger battalions of American troops. Their luck ran out at Bear Paw,

on the last day of September. The Indians were hungry, some of them frostbitten, when

the soldiers surrounded them. Joseph surrendered with the memorable words, “My heart

is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

The survivors, and Nez Perce sympathetic to Joseph who were not part of the war,

were manacled, shipped to a prison in Kansas and then to a six-hundred-acre compound

that was little more than a POW camp in the designated Indian Territory of Oklahoma.

During the first four years in Oklahoma, 103 of the 431 Nez Perce died. By 1885, Joseph

and his followers were allowed to move to the Colville reservation of central Washington,

home to more than half a dozen different tribal bands, none of them particularly friendly

to the Nez Perce. Colville was still a long way from the green meadows of northeastern

Oregon, which Joseph’s people had been promised by earlier treaty. The struggle to

see the sun rise again in the Wallowas consumed the last quarter century of Joseph’s

life.

The press in New York wasn’t interested in any of that. Broken treaties were old news.

The Wallowa Valley? Couldn’t find it on a map. A wild Indian on Broadway, especially

one so photogenic, in full-feathered head bonnet—that was a story. “The Red Napoleon,”

reported the

New York

Sun,

was “tall, straight as an arrow, and wonderfully handsome.”

It was on his second trip to the East, months before the football game, that he met

Teddy Roosevelt. At the same time, his former enemy, General Oliver Howard, whose

six hundred men had been surprised by one of the attacks from a small force of fleeing

Nez Perce, invited the chief to speak at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in

Pennsylvania. This institution was a high-minded boarding school for Indians from

all over the country. The students came in as savages, educators proclaimed, and came

out as model citizens. Joseph spoke to the children in his native tongue, as always,

which only a few of them could understand. What exactly did he say? The teachers and

important guests gasped when they heard the translation: “For a long time I wanted

to kill General Howard.”

In Seattle, Joseph’s escort was a red-bearded, buoyant young professor of history

at the University of Washington, Edmond S. Meany. Like Curtis, Meany was a Northwest

Renaissance man, drawn to the wonders of the fledgling city by the sea. And like Curtis,

he had come from the Midwest and a family that had lost its father at a young age,

forcing Meany to be the breadwinner while still a teenager. Meany did not look down

on Curtis for his lack of education, and Curtis did not begrudge Meany his advanced

degrees. They became fast friends. Meany was tall, persuasive, an intellectual omnivore.

Before his thirtieth birthday, he had started a news agency, been elected to the state

legislature—where he was instrumental in passing a bill that made tuition free at

the two state colleges—and climbed the highest peaks in the region. He also founded

his own alpine club, the Mountaineers. He was fascinated by native people, especially

those east of the Cascades, and took up their cause while still a student, earning

his master’s degree in 1901 with a thesis on Chief Joseph. The professor and the tribal

leader were so close that Joseph gave Meany an Indian name, Three Knives. It was Meany

who publicized the notion that this most famous of living Indians was “practically

a prisoner of war, receiving rations and requiring permission to leave the reservation.”

Though he taught forestry, American history and the occasional literature class, Meany

was at his professorial best when expounding on Indian life. He wanted his students

to see Indians not as an academic subject, not as trees to be closely examined or

distant historical figures to be deconstructed, but as living people who understood

the Northwest better than any who came after them.