Shutterspeed (13 page)

Authors: Erwin Mortier

I took off the dressing gown and crept under the icy covers. Not three weeks had passed since my departure, but the wall beside the bed already gave off the brackish smell of abandoned buildings.

I sank into a slumber that felt like a body of water closing overhead. In the course of the night the fever raised me periodically to the surface, where I bathed in sweat. I turned over on my side and curled up, hugging my knees to my chest. I tumbled down snow-covered slopes, rolled through savannahs, dreamed of forests where the only sounds were birdsong and raindrops splattering on the foliage. All my tossing and turning had stencilled the sheets with an assortment of sweaty contours, so that I seemed to be lying back to back with myself.

Lianas twisted themselves about my ankles. I started awake from their stranglehold and got out of bed to fetch a glass of water. My sweat-drenched vest was a cold harness encasing my ribcage.

I stole through the darkened house to the scullery. All I longed for was to let go, topple over backwards, and

heave a succession of sighs so that I might at length be subsumed into the plaster on the walls.

I held the glass under the tap, downed it in two, three draughts, filled it again, and again, and yet again, until the rawness in my throat had passed.

I don’t know what time it was, but it must have been close to midday, for broth being prepared in the kitchen could be smelt all over the house. Saturday – miserable weather and cups of hot broth.

I was lying on my back. I must have slept with my mouth open because my palate felt like sandpaper when I swallowed.

Sitting up at last I felt the sodden state of my sheets and realised I had wet myself. I leaped out of bed, swearing under my breath. I stripped off my underwear, put on the dressing gown and went to the bathroom with my vest and pants tucked under my arm.

I stood in the tub to have a wash, not daring to glance at my reflection in the mirror over the basin. After towelling myself dry, I rinsed out the underwear, shivering from cold and from the trickles of yellow on my fingers. It was all in vain, of course. When Aunt came upstairs later to make the beds she certainly noticed the state of my sheets. I cringed with embarrassment.

I threw the damp underclothes in the laundry basket on the landing, and when I was back in my room putting on a clean vest I heard something outside: a metallic scraping noise from across the road.

I squeezed between my writing table and my bed to get to the window and pushed the net curtain aside.

Raindrops slithered over the panes. The plastic sheeting across the road sagged in places from the weight of the collected rainwater.

I could see Uncle Werner talking to the priest, who held one hand to his head to stop the rising wind from whipping off his hat. Both of them were looking down at a third person, of whom I caught only the occasional glimpse: a bent back, a cap, an elbow, a hand gripping the handle of a spade or some other implement.

The wind tore at the long mackintosh the priest wore over his cassock. At one point I saw Uncle looking the other way, perhaps to avoid the lashing rain. He gazed out over the churchyard stretching out before him like a cratered, lunar landscape, which looked as if some giant marmot or mole had been burrowing into the ground to excavate a series of tunnels.

The priest nodded in response to something Uncle said. The third figure drew himself upright. I recognised him as a local man who was employed by the public works department. He stood with muddied hands beside Uncle and the priest, all three of them with their heads down, staring at something at their feet. Then the workman bent over again. The priest turned to Uncle Werner and spoke a few words.

The rain intensified. I saw them confer about taking shelter from the downpour. The man appeared to be lifting something. The three men moved towards the road, where they were screened from view by the plastic sheeting.

I was on the landing, poised to start down the stairs when I heard them come in. Boots were stamped on the doorstep.

‘We might as well wait for them here,’ I heard Uncle say. ‘Better than drowning under a tree …’

They were pushing and shoving some heavy object.

‘Yes, leave it here. That’s all right … we’re closed anyway.’

I heard them go down the passage to the kitchen. I buttoned up Uncle’s dressing gown and went downstairs.

‘Anyone for some good hot broth?’ Aunt called from the range. ‘Or something stronger, perhaps … or would you prefer a cup of coffee?’

When I came down all four of them were sitting around the table. The workman added a dash of genever to his coffee. The priest knocked back a thimble-sized glass of liquor and breathed out through clenched teeth. They had not noticed me yet.

‘So you see,’ said the priest, ‘some things are best left undisturbed …’

I saw Uncle Werner nod in agreement.

‘Ha!’ cried Aunt. ‘He’s awake. You look a sight better already. Can I get you something to eat, lad?’

I shook my head. ‘Don’t think so. Wouldn’t keep it down anyway.’

‘Bearing up all right over at the Jesuits?’ asked the priest. ‘Not the gentlest of folks by all accounts, eh?’

I shrugged my shoulders. ‘Not bad.’ Then I felt compelled to say I was sorry about the canopy, last summer.

‘Not to worry,’ he said, laughing indulgently. ‘Just a

little accident, that’s all …’ He turned to face the company again.

‘It’s a funny business, though,’ I heard the workman say. ‘Not that I haven’t seen my share. Remember Richard, the old gamekeeper? Yesterday, it was. And the little girl, daughter of the baker’s brother-in-law … All look the same in the end …’

Aunt laid her hand on his arm. ‘Are you sure you don’t want some of my nice broth? Shame to let it go cold. Come on, folks, have a taste.’

She stood up and went through to the scullery.

I left the men behind and lurked in the passage.

My father. It must have been close on ten years since I had last set eyes on him. Ten years in which it was not he who tossed me in the air, nor he who took me by the hand and showed me the way along paths I have since learned to walk unaided, despite the worsening bumps and potholes in the surface under my feet.

He stood on the mat in the doorway, looking as forlorn as a prodigal son seeking refuge from the wind and the rain. Behind him, in the porch, stood a pair of muddy boots and a spade, as if he had dug a tunnel from the other side of the globe just to be here.

I heard a faint echo of his laughter, his voice, his intonations, the expressions he used, the gist of which eluded me as it had in the old days. I was not yet thirteen, but he barely reached to my calves.

I heard Aunt calling my name, and then, more quietly,

addressing the men in the kitchen: ‘Where can he have got to?’

I looked down at the dark, mahogany box. She had bought him a handsome new trunk, had my mother, not much bigger than a suitcase.

I bent down, rubbed my thumbs over his shoulders of stained wood, ran my fingers over the braille of the plaque on the lid and felt the coolness of the brass handles on either side.

I heard a rushing sound, as if all the photos ever taken of him were suddenly rising from their albums and boxes and picture frames, as if he had let go of my hand to startle the butterflies that had hovered motionless over the hemlock ever since. But like as not it was only my head spinning faster and faster as I sank to my knees and laid my feverish cheek against the wood.

The dressing gown hampered me, so I untied the belt. I clenched my fingers around the handles. The box was lighter than I expected. Just as it rose up from the doorstep something came loose inside, rolled over the base and bumped hollowly against the back, followed by a dry rattle like jostling marbles.

The sound pierced me to the quick. I let go of the handles.

‘Joris?’ I heard Aunt cry.

I ran past her down the passage and up the stairs. In my room I stripped my mattress, bundled up my sheets, threw them on the floor, kicked them under my bed. I

drew the curtains to darken the room. The rain had lifted to a drizzle.

I sat down on the bare mattress in the sepia light filtering through the curtains. I don’t know how long I sat there.

A car pulled up on the cobbles. Someone got out, the engine was still running. The shop’s bell tinkled.

‘Anybody in?’ someone called. And I heard Aunt reply: ‘Yes, yes, over here.’

‘Can I ride with you?’ I heard a voice ask – the priest’s, by the sound of it.

The bell tinkled again.

‘I’ll join you later …’ Uncle called.

I got to my feet, crossed to the window, draped the curtain around my shoulders and stood with my fingers pressing on the wood of the sill, which was softened by age and sudden showers and seemed to be held in place by nothing but coats of paint.

I glimpsed a figure in a dark suit shutting the back of the hearse, and then I saw the priest getting in next to the driver.

Car doors thudded. They drove off. A while later Uncle hove into view, riding his bicycle down the path.

I turned round, let the curtains fall in folds over my head, went back to the bed and stubbed my toe against the table leg on the way.

I stood on one leg and swore, holding my aching foot in the air.

All I wanted was to stop moving, to just stand there

and turn to stone, even if I knew I looked stupid in my uncle’s flowing dressing gown with only a cotton vest underneath. In the commotion that morning I had forgotten to put on a clean pair of underpants.

There was a knock at the door.

Aunt said my name.

I kept silent.

‘Joris?’ she repeated.

I turned my back to the door and went to the window, where the glow of sunbeams suddenly breaking through the clouds lit up the weave of the curtain fabric.

‘Why don’t you say something, lad?’ She sounded fraught. Twisting the doorknob she said, ‘You’re not doing anything silly, are you?’

‘It’s all wet …’ I heard myself say in a small voice. ‘I’ve wet my bed.’

She let go of the doorknob.

I heard a sigh.

‘You poor thing. Never mind, it doesn’t matter. Come on, please open the door,’ she pleaded softly.

I turned the key, but first I buttoned up the dressing gown.

She entered, took my head in her hands and pulled me towards her.

I did not resist.

‘These things happen,’ she murmured in my ear, ‘what must out, must out …’

ERWIN MORTIER

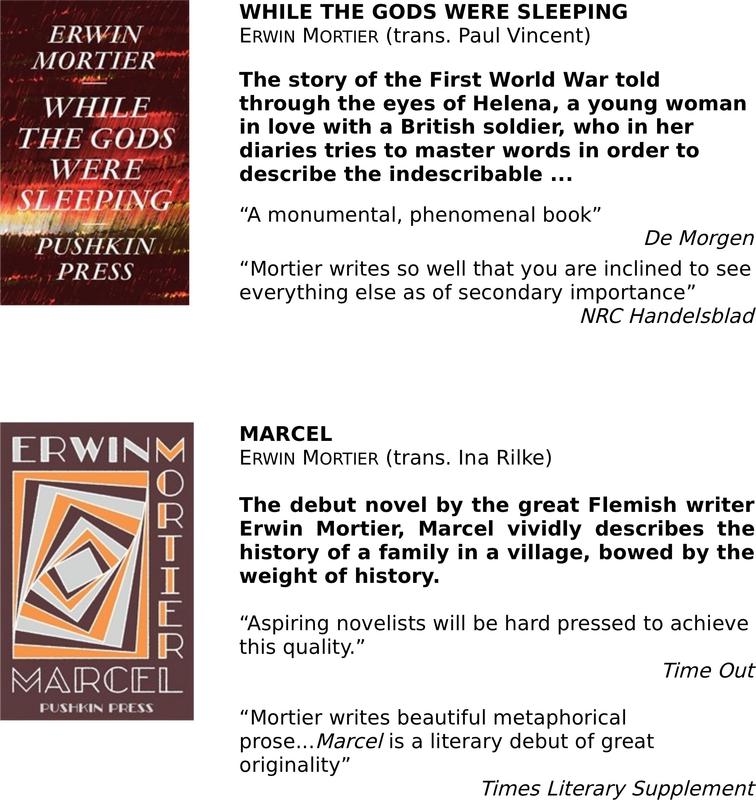

(born 1965) made his mark in 1999 with his debut novel

Marcel,

which was awarded several prizes in Belgium and the Netherlands, and received acclaim throughout Europe. In the following years he quickly built up a reputation as one of the leading authors of his generation. His novel

While the Gods Were Sleeping

received the AKO Literature Prize, one of the most prestigious awards in the Netherlands. His latest work,

Stammered Songbook

, a raw yet tender elegy about illness and loss, was met with unanimous praise. Mortier’s evocative descriptions bring past worlds brilliantly to life.

Pushkin Press was founded in 1997, and publishes novels, essays, memoirs, children’s books—everything from timeless classics to the urgent and contemporary.

Our books represent exciting, high-quality writing from around the world: we publish some of the twentieth century’s most widely acclaimed, brilliant authors such as Stefan Zweig, Marcel Aymé, Antal Szerb, Paul Morand and Yasushi Inoue, as well as compelling and award-winning contemporary writers, including Andrés Neuman, Edith Pearlman and Ryu Murakami.

Pushkin Press publishes the world’s best stories, to be read and read again.

Pushkin Press

71–75 Shelton Street, London WC2H 9JQ

Original text © 2008 by Erwin Mortier.

In a licence from De Bezige Bij, Amsterdam.

English translation © Ina Rilke, 2007

Shutterspeed

first published in Dutch as

Sluitertijd

by Cossee in 2002

This translation first published in 2007 by Harvill Secker

First published by Pushkin Press in 2014

This ebook edition first published in 2014

ISBN 978 1 782270 88 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from Pushkin Press