[sic]: A Memoir (10 page)

Authors: Joshua Cody

“I have something to tell you that’s very difficult for me to say.”

She glared at me through the corner of an eye, gauging whether I was prepared for a momentous and disturbing revelation, a horrific item that concerned not only her but me.

Note to reader: if you are ever unfortunate enough to find yourself in a close relationship with someone who has a life-threatening disease, and for whom conventional treatment has failed, and who is facing a “salvage” treatment that itself is life-threatening, DO NOT DO THIS. Because your friend will know what I knew, not imagined, feared, nor thought: Sophie had just talked to a nurse; this nurse was surprised that Sophie hadn’t been informed I was going to die that afternoon.

“I was cleaning your apartment, and I found it,” she said.

Found

what?

I wondered. I couldn’t think of anything. A mildewed washcloth? Doubt it. Dirty laundry? Couldn’t be, everything was at the cleaner’s. Pornographic literature? Probably not—how would she know? It’s all in French.

The glare was now bitterly accusative—I’d forced her to say it. “The cocaine.”

Cocaine? I hadn’t had a line of cocaine since that one night way back in October or November or whenever it was, when I hit the Golden Ratio. And I’d only ever actually had any in my apartment once. I’d never bought any. I might have had some pot laying around—a drug-dealing friend of mine had given me some for the chemo, but I never took to it. I suppose it was possible that there was a dollar bill folded into triangular eighths with some cocaine in it somewhere, an accidental residue from one of the rare points in the past when I had in my possession a dollar bill folded into triangular eighths with some cocaine in it.

No, she said, it was a whole bag. She’d found it on the bookshelf. She stared at it longingly for hours. She almost did a line. It would have sent her back straight to hell. All of her effort, all of her work against addiction, for naught, because of me. I almost killed her.

Luckily—she had no idea where she found the strength—she flushed it down the toilet. Again, I thought of

Goodfellas

: Lorraine Bracco in her bathrobe, with a firearm in her panties, flushing sixty thousand dollars’ worth of powder into the sewers of Long Island.

“How much was it?” I asked Sophie. And I wanted to ask her—Did you have a firearm in your panties?

She was crying. “I just wish you the best. But I cannot be around a cocaine addict. It’s too dangerous for me. I’m so sorry for you. I wish you the best, and I hope you have the strength to seek help. But I can’t be that person.”

Still, I felt as if I had to offer her something; I felt so guilty, having come so close to horribly murdering her. “It could have been some of that stuff Mike gave me back in October, but I really don’t—”

Sophie put up a thin pale elegant wrinkled dry hand. “Stop. Please. Don’t make this harder than it is.” She came over to the bed, gave me a kiss on the cheek, and walked out of the hospital room and out of my life.

•

A COUPLE OF

years later I saw her again. She might have e-mailed me, or contacted me through Facebook, which I re

luctantly joined at the insistence of an unfortunate (for me) dalliance. Or maybe we ran into each other on the street, or in a restaurant. That might have been it. It was nice to see her. She looked great. She had been struggling a little with her design career, but things were looking better. I can’t remember the exact circumstances, but we agreed to get together for coffee in a couple of weeks. Lo and behold, in a couple of weeks, she called me as I was walking downtown to Battery Park to see a film. This time it sounded as if her teeth were clenched.

“Do you want to get a coffee?”

“Sure,” I said.

“Where are you?”

Odd question. “Right now? I’m walking down to Battery Park. Why?”

“Because I’m around the corner from your apartment. Do you want to come back to your apartment and make coffee?”

No, I thought. I don’t. “I’m on my way to see a film. I’m halfway down to Battery Park.”

“What street are you on, exactly? I’m driving. I’ll come meet you.”

“Okay, I’m on West Broadway and Warren—”

Our conversation was briefly interrupted by the sound of scraping metal. “Fuck! Sorry, hang on, I just hit some asshole. Listen, wait there, I’ll be right down.” She hung up. Her parents had something like thirteen Mercedes.

Given the automobile accident, she made good time. We went into a Viennese-style café; I ordered an espresso. She ordered a doppio venti nonfat mocha soy vanilla hazelnut white cinnamon thing with extra white mocha and caramel, a scissors, a roll of Scotch tape, and a Scotch tape dispenser.

“What?” said the barista.

“One doppio venti nonfat mocha soy vanilla hazelnut white cinnamon with extra white mocha and caramel, a scissors, a roll of Scotch tape, and a Scotch tape dispenser.”

“You want a scissors, and Scotch tape?”

So this meeting was sort of a nice bookend to our hospital check-in, when she berated the woman on the cell phone. But just like the woman on the cell phone, the guy was compliant; maybe people treated Sophie with such sympathy because her vulnerability was so apparent, as were her brave attempts at masking it. He gave her the scissors and the tape, and she sat right down at the biggest table in the place, pulled out her massive leather portfolio, and got right to work, matting huge printouts of design prototypes. I tried making conversation, but I felt bad, interrupting her concentration. I did learn that she was going through a dry spell sales-wise, and had moved temporarily back into her parents’ McMansion, the thought of which, she said, turned out to be more depressing than the actual experience, which was actually kind of fun, hanging out with them, not living alone, not constantly worrying about rent.

That’s about all I learned. I sat there in silence for a time, watching her slowly cut ecru cardboard along scored lines, unwinding a strip of tape from the reel, applying it with a single bony finger.

I watched her single finger, tracing a line.

And all of a sudden, it occurred to me.

After I learned that the chemotherapy didn’t work and that therefore things looked a little dimmer, but before I started up the next treatment, I had made a little, very modest feature film with some friends, because one of the things I’d always wanted to do in life—ever after having seen

Raiders of the Lost Ark

after having read an early draft of the screenplay a family friend somehow had been able to secure or steal from Lawrence Kasdan or somebody close to him (I know I said before I wasn’t interested in the arts as a child but that actually wasn’t true), I had memorized the screenplay and had essentially directed the film in my head, so every directorial decision, every cut or added scene, was a revelation—was to make a movie (and I would recommend it to everyone, by the way). My movie contained a scene in which a character, at a party, does lines of cocaine. We went through various mixtures of vitamin B

12

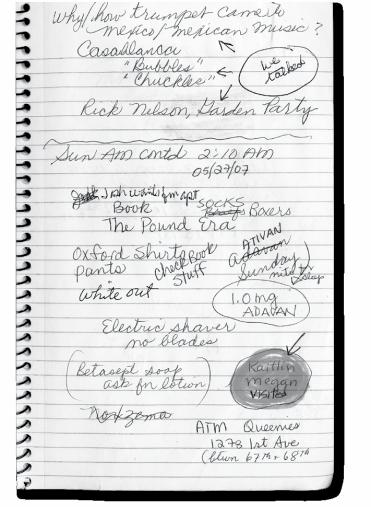

, powdered milk, corn starch, powdered goat milk, soy baby formula, and baking soda before coming up with a simulacrum authentic even at macro-lens close-ups. Packed into little plastic bags, it was very convincing—even for an ex-addict. Afterward, I threw the props into a bag and brought it home and forgot about it.

Never had the heart to tell her.

V

SISTER MORPHINE

Le R

ê

ve est un seconde vie.

[Dreaming is a second life.]

—Gérard de Nerval, “Aurélia, ou Le Rêve et la vie.”

At this point a question may well have been inadvertently

raised, if not voiced, and thus may merit address: how did these words end up in front of your eyes? One possible answer is that one morning I woke up in my little hospital bed, not more than a cot, really, in my little hospital room, not more than a cell, really, and I was suddenly bored enough to write these words down in a journal, the words that are now floating before you. I started at the beginning—not the beginning of the volume you currently hold; that beginning was added toward the end. No, I started here, with these words, “at this point,” at the beginning, the omphalos and all that, how my mother (as I began writing, in longhand) had graduated from high school in 1910, in Vienna—how long ago that seemed, how far away. And how (I continued) this was such a big deal, for a young woman in Central Europe in 1910; even if it had been a few years later, it would still have been a big deal. So my mom’s parents, brimming with pride, wanted to celebrate; they went to the great Hapsburg port of Trieste, and that’s how the whole story really began.

They stayed for a week at a hotel with a terrace right on the water. One night my grandfather (he claimed) spent a whole night drinking with James Joyce, who, he said, told him he’d hatched a scheme to import textiles from Ireland that would forever absolve him of financial turmoil. My grandfather covered the tab because, in his words, “From the moment I set eyes upon this man, I knew that while fortune would forever elude him, fame most certainly would not.” My grandmother didn’t believe it. I like to think it’s true. Merely embellished, maybe.

After the week in Trieste, my grandparents put my mom on a steamship to Egypt, for a month-long stay with Uncle Al. The idea was self-improvement as well as celebration: Alexandria, the jewel of the Mediterranean, was the most diverse and cosmopolitan city in the living museum of Egypt. And my mom would perfect her French. And Al was doing well: he’d moved from Austria to Constantinople before the turn of the century to set up emporia. This wasn’t that unusual; Austria had long been Central Europe’s conduit to the Levant, and there was money to be made there. Al’s store became a chain: after Constantinople he opened a second down the Turkish coast, in

I

zmir (then Smyrna); a third, moving east, in Aleppo, Syria; a fourth in Alexandria. But my mom’s month-long visit became a four-year stay with my father-to-be, an aspiring poet from London. My father’s family had been in England for a couple of generations, but they were originally Hungarian Jews, so there was common ground: the binding soil of Central Europe, the binding culture of the Hapsburgs. I’m certain my parents regarded these four years in Alexandria before Ferdinand’s death as the loveliest in their lives. How couldn’t they? Tennis at the sporting club, gimlets at sunset, the warmth of Alexandrian dusk. My dad had a sinecure at the British Post Office that let him write as much verse as he wanted; my mom, a contralto, sang Maddalena and Cherubino at the Alexandria Opera. Then I was born, and then the world exploded.

My father took us back to London when Britain declared war on the Ottomans, correctly predicting that the British military’s deposition of the khedive would ignite a revolution. The irony that he would meet his death two years later during this very conflict needs no underscoring. After my father was killed, my mother and I moved to Budapest, a mid-size apartment on Andrássy Street, four blocks away from the Liszt Academy. Budapest, for her, was a way to extend the marriage in her mind. London would have been impossible; his absence was too obvious. In Budapest, there were distant relatives of my father: perhaps she felt that dim traces of light imply long distances to bright, still-living sources.

Alexandria, Egypt, c. 1920.

She never sang after my father died, but she taught me piano, and by the time I applied for school, I knew I was good enough to get into the Liszt Academy, and I was right. I didn’t think I was good enough to get into Vienna, but I was wrong. Vienna! Mozart and Beethoven and Mahler and Sibelius. When I got the letter I ran over to my friend Andy’s place (Andy was my best friend, a dark, slightly melancholic character who wore bow ties and a mustache and was an excellent violinist, but we knew he was doomed to a career in law). Vienna! Andy couldn’t believe it. He and the whole gang took me out that night to this place we loved, a dark restaurant in a basement where the beautiful Romanian girls would go, and late at night these terrific folk musicians would play on old instruments, reed violins and jughorns, hurdy-gurdies and dulcimers. But we mainly loved it because the owner would let us drink. Drink we did. Andy ordered a fifth or sixth round and raised his glass “to Vienna!”

I said, “Vienna? I’m going to Budapest.”

A pin dropped. I felt like the whole restaurant was staring at me. I didn’t realize it then, but we were what you’d call bourgeois intellectuals, everybody was studying philosophy and history and classics. We were also Hungarian nationalists—except for tonight.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“What’s the matter?” Andy said. “Nothing. I love watching my friends throw their lives away.”

“Throwing my life away,” I said. “Right. Just like Reiner and Solti and Sándor did, only the most successful musicians in America. I’ll study with Bartók, that hack.” As the waitress brought our food, deep-fried calves’ brains and stuffed cabbage and veal-filled pancakes and cold cherry soup, Andy held my arm. “You’re joking, right?” he said. No, I said.

“We’re stuck here,” Andy said. “You can escape! You’re going to die four blocks from where you were born!”

I said, “Andy, I was born in Egypt.”

We ate and drank and argued and flirted with the girls and debated the pros and cons of Vienna and Budapest and didn’t really talk about some other aspects regarding moving to Vienna in 1934. It isn’t that we were avoiding it. We would talk about it, all of us would. Just not that night. But everybody talked about it. But then again you have to understand that people would talk about a lot of things. So often it’s only in retrospect that one traces the disease to a symptom, whereas in the heat of the moment every nerve ending of the body is clamoring for one’s attention. Perhaps this isn’t the worst place to remind ourselves of the astonishingly complex design of one’s momentary field of vision, forever bursting (well not forever, but you know what I mean) not only with the immediate stimuli of the present moment—Andy’s law-school-ish counterarguments, for example; or the delicious crunch of deep-fried brains; the sharp green eyes of a Romanian girl in a white dress; a newspaper photo, yellow and brittle as a dead moth, of Hitler, taped to the wall; the watery crash of a beater hitting a dulcimer; Andy ordering another round of drinks and laughing and shaking his head. We’re bombarded not only with these, but with the recalled stimuli of the past as well. And these two layers wrap around each other like two electric currents encircling some wobbly magnetic pole. Some of these stimuli, both the remembered and the immediate, will, in the future, be remembered, some forgotten; and some of those remembered will, in retrospect, be trivialities: and a few will be History.

•

THE FIRST DAY

of classes, I walked by a practice room and heard a violin student playing the opening of Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata. It was marvelous. The Kreutzer begins with a solo violin; the pianist enters fifteen seconds after, with an A major chord. It was as if I’d never heard an A major chord before, and at that moment I knew I would never be a pianist.

Next, two cold d minor chords, and at that moment I was thrown into despair; what would I be, then?

Next, a whole measure of E dominant seventh, a sign of hope, and I knew I would be a writer.

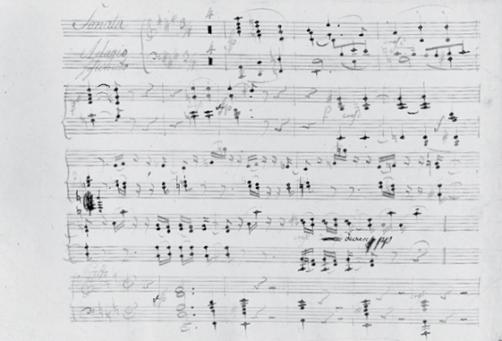

First page of Beethoven’s manuscript of the Kreutzer Sonata for violin and piano, with Beethoven’s corrections, 1803.

I peered through the door’s small square window and glimpsed the pianist’s face. F major! This, in music, is called a deceptive resolution. The phrase is self-descriptive, really; you’re expecting something, and something else happens instead, and it’s marvelous. In music, the E chord is “supposed” to lead to an A chord, so when it leads to an F chord instead, colors shift slightly and deepen, like you’re suddenly staring through a small square window into the eyes of the girl you know you’ll marry. The funny thing is that I was always afraid, even after the wedding, that I wasn’t really in love with Valentina, but with that particular F chord, and she just happened to have perfectly coincided with it on the space-time continuum. But I would calm myself by remembering that she, as well as Beethoven, was the creator of that chord—not just her exquisite Bulgarian hands but her very being: not just her exquisite figure but her entire landscape.

•

THIS STORY ISN'T

really about my marriage to Valentina, this Bulgarian girl with serious, almost-almond-shaped eyes, low voice, unblemished olive skin, and bony ankles who always seemed to be enveloped in a scent of violets. If it were, I’d relate little anecdotes—like the time we were, the two of us, alone in a practice room at the academy; she was grading papers, and I was fooling around on the piano, stumbling my way through the middle movement of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto. She came over to the piano and sat beside me, eyes twinkling. “Yes,” she said, “you can play!” But she took over, as did a kind of dream; she closed her eyes and, referring to the piano, said—

—you see, it

sings

.

But this story isn’t about that, so I feel justified in skipping ahead a few years to 1963, when the Rolling Stones signed a record deal for the first time and when I, at the tender age of forty-nine, was for the first time thrown in prison. By then I had a column on music in the most prestigious magazine in Hungary. I’d written a dual profile of two composers I knew, Ligeti and Kurtág. For me, they were the greatest composers in Europe; they divided Europe between them and there was no third. Ligeti’s music was expansive, scored for huge orchestras, and dealt with immense sheets of shimmering sound that seemed to freeze time; Kurtág’s music was miniature, employing just a few musicians, neurotically fixated on the tiniest details. Ligeti had fled Hungary for the West after Kádár, the prime minister, crushed the 1956 student uprising; Kurtág stayed. Both Ligeti and Kurt

á

g were Jewish. But Ligeti was sent into a forced labor camp during World War II. His brother had been sent to Mauthausen, and he died. Both of his parents had been sent to Auschwitz. His mother had survived and his father had died. Might these be reasons why Ligeti fled Hungary? I certainly didn’t suggest such a thought in my article. So when I received an invitation to the prime minister’s office after the article came out, my editor and I had no idea what to expect. I remember waiting with my editor in the plush antechamber of the Office of the Prime Minister, perched on the Danube, about twelve blocks from the apartment Valentina and I had bought on Andrássy Street, two blocks away from the Zeneakadémia, and two blocks away from the apartment in which I grew up. I remember wondering if we were actually going to meet Kádár. We didn’t. The minister of culture let us in. We knew him casually. He enjoyed the article, he said. Then he asked if I would be amenable to help the Hungarian government.