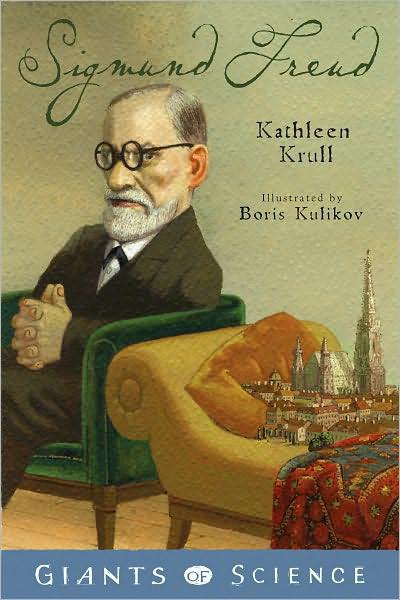

Sigmund Freud*

Table of Contents

VIKING

Published by Penguin Group

Penguin Young Readers Group, 345 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), Cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2006 by Viking, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group

Published by Penguin Group

Penguin Young Readers Group, 345 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), Cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2006 by Viking, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group

All rights reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA IS AVAILABLE

eISBN : 978-1-440-67833-2

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means

(electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both

the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this

book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable

by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage

electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means

(electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both

the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this

book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable

by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage

electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

Welcome to Ethan Brewer, May 9, 2006

—K.K.

Acknowledgments

For help with research, the author thanks

Susan Cohen (Agenting Goddess),

Dr. Lawrence M. Principe, Stanley Bone, M.D.,

Patricia Daniels, Sheila Cole, Janet Pascal,

Paul Brewer, Melanie Brewer, Cindy Clevenger

and the Rabbits, and most of all, Jane O’Connor.

Susan Cohen (Agenting Goddess),

Dr. Lawrence M. Principe, Stanley Bone, M.D.,

Patricia Daniels, Sheila Cole, Janet Pascal,

Paul Brewer, Melanie Brewer, Cindy Clevenger

and the Rabbits, and most of all, Jane O’Connor.

INTRODUCTION

“If I have seen further [than other people] it is by standing upon the shoulders of giants.”

—Isaac Newton, 1675

THE BRAIN HAS NOT always gotten respect.

When turning a corpse into a mummy, the ancient Egyptians used a small hook to scrape brain matter out through the nostrils. Then they threw it away. After all, the brain did so little—everyone knew that intelligence and emotions arose from the heart, which

was

carefully preserved.

was

carefully preserved.

Ancient Babylonians revered the liver as the true source of thought and emotion.

The great thinkers of ancient Greece were divided. Some, including Plato, concluded from early anatomical studies that the brain was the center of intelligence. However, Aristotle, that powerhouse born in 384 B.C., insisted the center of thought was in the center of the body: the heart. The brain was merely a sort of air conditioner, cooling off the body from the heat the heart made with all that thinking and feeling.

Galen, the famous physician from the second century A.D., knew the mind resided in the brain, yet his approach to treating a mentally disturbed patient was way off the mark. Galen believed that four humors, or fluids, generated by the brain—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile—determined not only physical but mental health. An excess of yellow bile caused ill temper, for example; an excess of black bile caused melancholy or depression. Diagnosis was a matter of examining urine, and “cures” were often a matter of bloodletting and vomiting to rid the body of that excess bile. Galen’s four-humor theory dominated medical thought for more than a thousand years.

By the Middle Ages, surgeons—often the local barbers—were claiming that a “stone of madness” lodged in the head caused strange behavior. They would dig out bits of brain and a person could be “cured.” For a fee.

Even Leonardo da Vinci, Renaissance wonderboy and ahead of his time in so many ways, stuck to a prejudice about mental illness that was common in his day—a person’s face reflected what was going on inside, for good or ill. An ugly, deformed face was the outward reflection of a twisted, sick personality.

And well into the 1700s, peasant folk commonly believed that mental illness was either punishment for sin or the work of the devil. Or a character weakness—depressed people were blamed for lacking self-control. Physicians still searched for medical causes of dementia, attributing it to bad blood, bad air, even bad food, and attempted to treat it with medicines including some made from highly poisonous plants like hellebore. The main “treatment” was to hide people with problems away and shut them up. If they weren’t too troublesome you could lock up your mad uncle in the attic, or put your crazy sister out in the barn. For the uncontrollable, special hospitals kept them away from society—asylums that were more like jails.

Then came the Scientific Revolution, fully flowering in the work Isaac Newton began in the mid-1600s. The scientific method is about measuring, quantifying, observing the physical world, and testing those observations. Scientists made triumphant discoveries in areas where things can be seen—physics and chemistry, astronomy and biology. Through autopsy work in the 1600s, Thomas Willis, a British doctor, revealed that the brain was the center of both thought

and

sensation—it was a complexly structured organ, command central of the entire nervous system.

and

sensation—it was a complexly structured organ, command central of the entire nervous system.

The brain—scientists began to understand exactly how essential it was to life. By the 1880s, the field of psychiatry, the medical treatment of diseases of the mind, had been born. One of its first books was by the German doctor Theodor Meynert, who specialized in the anatomy and function of the brain. Meynert was a “psychiatrist,” a word just coming into use, replacing “alienist” (the patients were the “aliens,” locked away in asylums, mentally alienated from real life).

So science, it appeared, could be applied to human behavior. Scientists struggled with such questions as: Why do humans act the way they do? What does the brain control? What is normal and what is abnormal behavior? Could science be used to help troubled people? Where do our bodies end and our minds begin? What is the “mind,” anyway? Is it solely the turf of poets and philosophers? Or can scientists claim it as their territory as well?

Scientists started talking about the brain in two ways—as an anatomical entity and as an emotional mind. One is a physical organ that governs the nervous system, with different parts that control specific functions like speech and memory and the five senses—the neurological brain. The other is something we can’t see, a mind that decides what those memories mean and how they affect us—the emotional brain.

Into the late 1800s, psychiatry flourished, but by focusing on anatomy—what the physical organ of the brain did. Early psychiatrists treating diseases of the nervous system saw mental illness as the brain being out of whack. They searched for physical reasons for brain disorders—lesions in the brain, perhaps. “The modern science of psychology,” wrote American doctor William Hammond in 1876, “is neither more or less than

the science of mind considered as a physical function

.”

the science of mind considered as a physical function

.”

There were some quirky detours taken while investigating the brain. Two doctors from Vienna—Franz Joseph Gall and Johann Spurzheim—promoted a popular pseudoscience called phrenology. They believed that the brain had some thirty or more separate organs, each of which controlled a different personality trait such as intelligence or criminal tendencies. Phrenologists believed that bumps on a person’s skull corresponded to various organs and dictated a person’s character. They would visit asylums and “prove” how the shape of the patients’ heads matched their illness. Phrenologists also prized owning the skulls of geniuses. Mozart’s was the trophy of one collection.

Consideration of the emotional mind, the thing that can’t be seen, lagged behind the study of the physical aspects of the mind. By the nineteenth century, treatment of the emotionally disturbed may have become more humane at least, yet it remained largely ineffective. Rest cures, for example, helped give patients peace and quiet, but didn’t treat the underlying causes of the sickness. No one thought of listening to patients, trying to figure out what ailed them. They spouted nonsense, so paying attention would just make them worse.

Meanwhile, as the twentieth century approached, another doctor from Vienna sat in a quiet room with troubled patients lying on a very important couch. Chain-smoking cigars, he listened and kept on listening. His faithful dog napped at his feet, trained to recognize when a patient’s hour was up. Furiously the doctor would write up case studies that read like mystery stories.

He pioneered a treatment called talk therapy, based on the theory that unconscious fears can make people sick. Uncovering those fears would help banish the illness.

His name may ring a bell—Sigmund Freud.

Freud didn’t answer all the questions about the emotional brain. And often the answers he did come up with were wrong. But he was among the first doctors to believe that psychology was actually a branch of science. Freud certainly didn’t discount the physical brain, but he primarily dealt with emotions, through his talk therapy, or psychoanalysis. Freud theorized that the emotional mind could make the physical body ill, and that’s what he wanted to treat—the memories, emotions, dreams.

“We have the means to cure what you are suffering from,” he told the “Wolf Man,” one of his famous patients. “Up to now, you have been looking for the causes of your illness in the chamber pot.” No more looking at urine, as Galen would have, nor bumps on the skull and other notions from centuries past.

Today, because of Freud’s work, we take it for granted that there are sometimes hidden motives for what we do. We understand that childhood experiences mold our later life, that dreams may have important meaning, and that private fears may loosen their grip if discussed openly.

According to the mighty Newton, scientists make their discoveries by standing on the shoulders of those who came before them. Science is incremental, step by step, with no discovery made in a vacuum, no “Eureka!” moments. So whose shoulders did Freud stand on?

Exceptionally well-read, Freud had many mentors—one of them was Theodor Meynert—and he owed a complicated debt to the science of his day, starting with his idol Charles Darwin’s revolutionary theory of evolution. But in inventing a system and vocabulary for studying the emotional brain—used for generations after him—he largely worked alone. Many (including Freud himself at times) questioned whether he was a true scientist—his work didn’t have some of the hallmarks of the scientific method, like experiments with results that could be duplicated. He felt jealous of people in sciences like physics who could present proof for their theories—he admitted he didn’t have it (yet). Freud was like an explorer, hacking through a thorny jungle all alone. “No wonder that my path is not a very broad one, and that I have not got far on it.”

Other books

Finding Serenity (Serenity Beach) by Keane, Hunter J.

Last Friends (Old Filth Trilogy) by Gardam, Jane

The Measby Murder Enquiry by Purser, Ann

The Root of Thought by Andrew Koob

Written in Red by Anne Bishop

The Shipping News by Annie Proulx

The Romantic by Barbara Gowdy

Joe Bruzzese by Parents' Guide to the Middle School Years

Space Plague by Zac Harrison

Ghost Girl in Shadow Bay: A Young Adult Haunted House Mystery by Flowers, R. Barri