Signor Marconi's Magic Box

Read Signor Marconi's Magic Box Online

Authors: Gavin Weightman

Table of Contents

By the same author

The Making of Modern London: 1815-1914

The Making of Modern London: 1914-1939

London River

Picture Post Britain

Rescue: A History of the British Emergency Services

The Frozen Water Trade

The Making of Modern London: 1914-1939

London River

Picture Post Britain

Rescue: A History of the British Emergency Services

The Frozen Water Trade

For my father

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My greatest debt is to Louise Jamison, archivist of the Marconi Company, who found the time to unearth for me many newspaper cuttings, diary extracts and illustrations and who made me welcome at Chelmsford, where the records going back to 1896 are kept. Gordon Bussey, the company’s historical consultant, provided much technical assistance, in particular on the details of the first transatlantic signal of 1901. At the Villa Griffone, Barbara Valotti made me welcome, and Maurizio Bigazzi demonstrated some of Marconi’s very early equipment and showed me the lie of the land. Professor Giuliano Pancaldi of Bologna University gave me some valuable background information and a handsome book, some of which was translated for me by Mariluisa Achille. The only really intimate account of Marconi’s life is in his daughter Degna’s memoir

My Father, Marconi

.

My Father, Marconi

.

A very special thanks to Thomas H. White, an American I have not met but whose personally compiled website ‘United States Early Radio History’ contains an astonishing range of original material in the form of newspaper and magazine articles dating back to the late nineteenth century, many of which are not available in Britain. As always the British Library and the London Library were invaluable, and I would like to thank Kate Simpson and Patrick McDonnell for their diligent digging in the newspaper archives at Colindale.

Susan J. Douglas’s wonderful academic work

Inventing American Broadcasting

was an inspiration early in my research, and Mary K. McCleod’s

Marconi: The Canada Years

provided a valuable account of the first wireless stations in Nova Scotia. Brian Stewart in Toronto and Clare Beaton in London made some very pertinent

comments on early drafts of the book. At HarperCollins, Richard Johnson’s enthusiasm for the project was invaluable and Robert Lacey’s editing as meticulous and astute as always. I would like to thank them and my agent Charles Walker at Peters, Fraser and Dunlop for all their assistance with the book.

Inventing American Broadcasting

was an inspiration early in my research, and Mary K. McCleod’s

Marconi: The Canada Years

provided a valuable account of the first wireless stations in Nova Scotia. Brian Stewart in Toronto and Clare Beaton in London made some very pertinent

comments on early drafts of the book. At HarperCollins, Richard Johnson’s enthusiasm for the project was invaluable and Robert Lacey’s editing as meticulous and astute as always. I would like to thank them and my agent Charles Walker at Peters, Fraser and Dunlop for all their assistance with the book.

The history of early wireless is fraught with claims and counterclaims about who really invented what, and I have done my best to take an objective view. Any mistakes I have made are naturally my responsibility alone.

Gavin Weightman

London, September 2002

London, September 2002

INTRODUCTION

It was the most fabulous invention of the nineteenth century. The public and the popular newspapers regarded it as nothing short of miraculous, and the leading scientists of the day in Europe and America, whose discoveries had made it possible, could not understand how it worked. Wireless in its pioneer days had nothing to do with home entertainment: no speech or music was transmitted. But the tap, tap, tap of the telegraph key spelling out messages which had travelled mysteriously through the ‘ether’ was exciting enough in a world still mostly horse-drawn and coal-fired, a world without cinema or the motor-car, in which the telephone was still an expensive luxury and great cities like London and New York had only recently winced at the brightness of electric light.

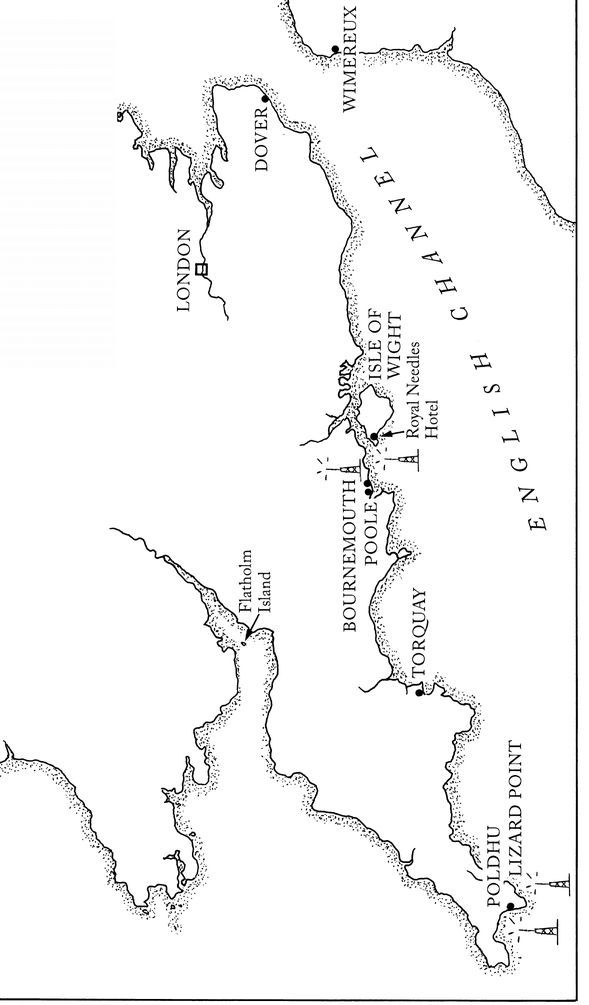

The wider world first learned about the possibilities of wireless telegraphy, as the new invention was called, in 1897. In November that year the very first wireless station was established in the exclusive Royal Needles Hotel. This splendid clifftop Victorian pile took its name from the nearby pillars of eroded rock which jut into the sea on the western corner of the Isle of Wight, a short ferry-ride off the south coast of England. An odd assortment of wires strung out on posts tethered to the ground to secure them against the stiff sea breezes and the not infrequent gales was the only outward sign that mysterious signals were being sent to the steamers, packed with skylarking holidaymakers, which plied the coast. Guests at the Royal Needles were aware when the transmitter was in operation, for they could hear and sometimes see the crack of electrical sparks activated by a Morse code key pressed by one of the operators inside the hotel. The range of these signals was only a few miles. But the fact that it was possible at all to establish, by remote

control, communication with a ship steaming along at a rate of knots,

even when it was lost to view behind a cliff

, was nothing short of astonishing. The wonders of science, it seemed, would never cease.

control, communication with a ship steaming along at a rate of knots,

even when it was lost to view behind a cliff

, was nothing short of astonishing. The wonders of science, it seemed, would never cease.

Only the year before, the newspapers had been full of accounts of the ‘new photography’ called X-rays, which could ‘see’ through solid objects. The public now had to take in the amazing possibilities presented by the ‘new telegraphy’. Like most powerful new inventions, wireless had the potential to bring both good and evil to the world: could it be used, perhaps, as a weapon? Might an electric wave aimed at a battleship blow up its explosive magazine as surely as any shell from a shore battery?

This ‘new telegraphy’ was not only mind-bending in its apparent defiance of contemporary scientific understanding; there appeared to be a very real prospect of it completely replacing the network of telegraphic cables which in the previous half-century had been strung out over land and laid across the ocean beds, at colossal expense. At the very least it meant that ships at sea, including the great liners which were then carrying millions of European immigrants to North America, need never be out of contact with each other and with New York, Liverpool and London. The big question was: how far could these invisible waves travel through the ‘ether’, carrying Morse-coded messages which were decipherable at a receiving station?

In 1897, nobody had the answer to that question. The great majority of physicists who worked on what were known as ‘Hertzian waves’ very much doubted that they could be used for communication over distances greater than a mile or two. Even that range, which had already been achieved, was causing some puzzlement, for it was not known through what medium the waves from a wireless transmitter really travelled. Did they go through hills, or over them? Did they bend around the curvature of the earth’s surface? As they were akin to light and travelled at the same speed, why did they not simply dissipate into the atmosphere, never to be retrieved and decoded on the ground?

Though there were some ingenious speculations about how wireless waves travelled long distances there was no definitive answer until the 1920s, by which time radio had become a sophisticated industry, filling the airwaves with a cacophony of sound - much of it American. In the meantime, from 1897 until the cataclysm of the First World War, wireless telegraphy was woven into the social and economic fabric of the most sophisticated societies with astonishing speed.

This is the story of how one of the most extraordinary inventions in history came about. Taking the leading role in a cast of many brilliant and eccentric characters is Guglielmo Marconi himself, whose home-made magic box first brought the ‘new telegraphy’ to the notice of the general public. In his lifetime he enjoyed worldwide fame for the achievement of turning a boyhood fascination with electricity into an entirely new form of communication, and a huge industry. Marconi was one of the greatest amateur inventors of all time. It is remarkable testimony to the fragility of reputation that a man who could command such respect in his lifetime should now be relegated to comparative obscurity, and that the names of scores of his contemporaries who made radio work have no resonance at all for a generation addicted to the most modern form of wireless telegraphy: text messaging on a mobile phone. That Queen Victoria received text messages sent by wireless from the royal yacht to her home on the Isle of Wight more than a century ago will come as a surprise to those who imagine the technology of the mobile phone is almost brand new. The story begins way back in the days of dark streets, horse-drawn carriages, and the blood-curdling murders of Jack the Ripper.

Marconi’s Early Wireless Telegraph Stations

1

In Darkest London

O

n a winter’s evening in 1896 a brougham, a four-wheeled cab drawn by a single horse, left the fashionable stuccoed terraces of west London and headed eastwards along the dirt roads and cobbled streets of the capital, which glistened in the gaslight under a light rain. The passengers were a young man who had with him two large black boxes, and a gentleman in his sixties sporting a long grey beard, his thinning hair pasted to his head in a centre parting. Steam rose from the horse’s flanks in the dank air as the brougham rattled through the canyons of streets in the City and, leaving the Square Mile, came to the fitfully-lit roads of Whitechapel. This was the frontier of the notorious East End, where only a few years earlier Jack the Ripper had mutilated his victims and left them dead or dying in dark alleyways.

n a winter’s evening in 1896 a brougham, a four-wheeled cab drawn by a single horse, left the fashionable stuccoed terraces of west London and headed eastwards along the dirt roads and cobbled streets of the capital, which glistened in the gaslight under a light rain. The passengers were a young man who had with him two large black boxes, and a gentleman in his sixties sporting a long grey beard, his thinning hair pasted to his head in a centre parting. Steam rose from the horse’s flanks in the dank air as the brougham rattled through the canyons of streets in the City and, leaving the Square Mile, came to the fitfully-lit roads of Whitechapel. This was the frontier of the notorious East End, where only a few years earlier Jack the Ripper had mutilated his victims and left them dead or dying in dark alleyways.

Other books

Untold Damage by Robert K. Lewis

Hidden Things by Doyce Testerman

Enemy in Blue by Derek Blass

A Bobwhite Killing by Jan Dunlap

Six Heirs by Pierre Grimbert

Flame and Slag by Ron Berry

Legends of the Martial Arts Masters by Susan Lynn Peterson

Beg Me to Slay by Unknown

Secret Value of Zero, The by Halley, Victoria