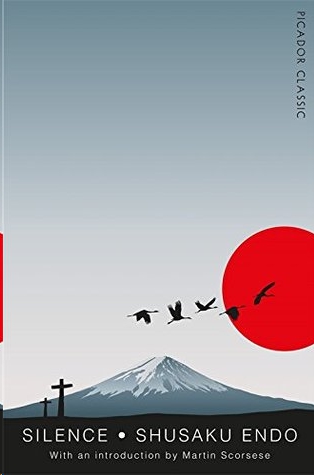

Silence

Silence

by S

HUSAKU

E

NDO

Translated by William Johnston

Taplinger Publishing Company New York

Translation Copyright © 1969 Monumenta Nipponica

Originally published as Chinmoku in 1966

This translation first published in 1969 by Monumenta Nipponica, Tokyo

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78-271168 ISBN 978-0-8008-7186-4

Table Of Contents

Translator’s Preface

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Appendix

Translator’s Preface

SHUSAKU ENDO has been called the Japanese Graham Greene. If this means that he is a Catholic novelist, that his books are problematic and controversial, that his writing is deeply psychological, that he depicts the anguish of faith and the mercy of God—then it is certainly true. For Mr. Endo has now come to the forefront of the Japanese literary world writing about problems which at one time seemed remote from this country: problems of faith and God, of sin and betrayal, of martyrdom and apostasy.

Yet the central problem which has preoccupied Mr. Endo even from his early days is the conflict between East and West, especially in its relationship to Christianity. Assuredly this is no new problem but one which he has inherited from a long line of Japanese writers and intellectuals from the time of Meiji; but Mr. Endo is the first Catholic to put it forward with such force and to draw the clear-cut conclusion that Christianity must adapt itself radically if it is to take root in the ‘swamp’ of Japan. His most recent novel,

Silence,

deals with the troubled period of Japanese history known as ‘the Christian century’—about which a word of introduction may not be out of place.

I

CHRISTIANITY was brought to Japan by the Basque Francis Xavier, who stepped ashore at Kagoshima in the year 1549 with two Jesuit companions and a Japanese interpreter. Within a few months of his arrival, Xavier had fallen in love with the Japanese whom he called ‘the joy of his heart’. ‘The people whom we have met so far’, he wrote enthusiastically to his companions in Goa, ‘are the best who have as yet been discovered, and it seems to me that we shall never find … another race to equal the Japanese.’ In spite of linguistic difficulties (‘We are like statues among them,’ he lamented) he brought some hundreds to the Christian faith before departing for China, the conversion of which seemed to him a necessary prelude to that of Japan. Yet Xavier never lost his love of the Japanese; and, in an age that tended to relegate to some kind of inferno everyone outside Christendom, it is refreshing to find him extolling the Japanese for virtues which Christian Europeans did not posses.

The real architect of the Japanese mission, however, was not Xavier but the Italian, Alessandro Valignano, who united Xavier’s enthusiasm to a remarkable foresight and tenacity of purpose. By the time of his first visit to Japan in 1579 there was already a flourishing community of some 150,000 Christians, whose sterling qualities and deep faith inspired in Valignano the vision of a totally Christian island in the north of Asia. Obviously, however, such an island must quickly be purged of all excessive foreign barbarian influence; and Valignano, anxious to entrust the infant Church to a local clergy with all possible speed, set about the founding of seminaries, colleges and a novitiate—promptly despatching to Macao Francisco Cabral, who strongly opposed the plan of an indigenous Japanese Church. Soon things began to look up: daimyos in Kyushu embraced the Christian faith, bringing with them a great part of their subjects; and a thriving Japanese clergy took shape. Clearly Valignano had been building no castles in the air: his dream was that of a sober realist.

It should be noted that the missionary effort was initiated in the Sengoku Period when Japan, torn by strife among the warring daimyos, had no strong central government. The distressful situation of the country, however, was not without advantages for the missionaries who, when persecuted in one fief, could quickly shake the dust off their feet and betake themselves elsewhere. But unification was close at hand; and Japan was soon to be welded into that solid monolith which was eventually to break out over Asia in 1940. The architects of unity (Nobunaga, Hideyoshi and Ieyasu) were all on intimate terms with the Portuguese Jesuits, motivated partly by desire for trade with the black ships from Macao, partly (in the case of Nobunaga and Hideyoshi) by a deep dislike of Buddhism, and partly by the fascination of these cultured foreigners with whom they could converse without fear of betrayal and loss of prestige. Be that as it may, from 1570 until 1614 the missionaries held such a privileged position at the court of the Bakufu that their letters and reports are now the chief source of information for a period of history about which Japanese sources say little. All in all, the optimism of Valignano seemed to have ample justification.

Yet Japan can be a land of schizophrenic change; and just what prompted the xenophobic outburst of Hideyoshi has never been adequately explained. For quite suddenly, on July 24th 1587, while in his cups, he flew into a violent rage and ordered the missionaries to leave the country. ‘I am resolved’, ran his message, ‘that the padres should not stay on Japanese soil. I therefore order that having settled their affairs within twenty days, they must return to their own country,’

{1}

His anger, however, quickly subsided; most of the missionaries did not leave the country; and the expulsion decree became a dead letter. So much so that C. R. Boxer can observe that within four short years there was ‘a community of more than 200,000 converts increasing daily, and Hideyoshi defying his own prohibition by strolling through the gilded halls of Juraku palace wearing a rosary and Portuguese dress.’

{2}

Nevertheless the writing was on the wall; and ten years after the first outburst, Hideyoshi’s anger overflowed again. This time it was occasioned by the pilot of a stranded Spanish ship who, in an effort to impress the Japanese, boasted that the greatness of the Spanish Empire was partly due to the missionaries who always prepared the way for the armed forces of the Spanish king. When this news was brought to Hideyoshi he again boiled over and ordered the immediate execution of a group of Christian missionaries. And so twenty-six, Japanese and European, were crucified on a cold winter’s morning in February 1597. Today, not far from Nagasaki station, there stands a monument to commemorate the spot where they died.

Yet missionary work somehow continued with the Jesuits apprehensive but still in favour at the royal court; and it was only under Hideyoshi’s successor Ieyasu, the first of the Tokugawas, that the death sentence of the mission became irrevocable. From the beginning, Ieyasu was none too friendly toward Christianity, though he tolerated the missionaries for the sake of the silk trade with Macao. But here things were changing: for the English and the Dutch had arrived. Nor was it long before the role of interpreter and confidant was transferred from the Portuguese Jesuits to the English Will Adams—who lost no time in assuring the Shogun that many European monarchs distrusted these meddlesome priests and expelled them from their kingdoms. Ieyasu evinced the greatest interest in the religious conflict that was rending Europe, questioning the English and the Dutch about it again and again. At the same time his apprehension grew as he observed the unquestioning obedience of his Christian subjects to their foreign guides.

And so finally in 1614 the edict of expulsion was promulgated declaring that ‘the Kirishitan band have come to Japan

…

longing to disseminate an evil law, to overthrow true doctrine, so that they may change the government of the country, and obtain possession of the land. This is the germ of a great disaster, and must be crushed.’

{3}

This was the death blow. It came at a time when there were about 300,000 Christians in Japan (whose total population was about twenty million) in addition to colleges, seminaries, hospitals and a growing local clergy. ‘It would be difficult’, writes Boxer, ‘if not impossible, to find another highly civilized pagan country where Christianity had made such a mark, not merely in numbers but in influence.’

{4}

Even now, however, a desperate underground missionary effort was kept alive until, under Ieyasu’s successors, the hunt for Christians and priests became so systematically ruthless as to wipe out every visible vestige of Christianity. Especially savage was the third Tokugawa, the neurotic Iemitsu—‘neither the infamous brutality of the methods which he used to exterminate the Christians, nor the heroic constancy of the suffers has ever been surpassed in the long and painful history of martyrdom.’

{5}

At first the most common form of execution was burning; and the Englishman, Richard Cocks, describes how he saw ‘fifty-five persons of all ages and both sexes burnt alive on the dry bed of the Kamo River in Kyoto (October 1619) and among them little children of five or six years old in their mothers’ arms, crying out, “Jesus receive their souls!”

’.

{6}

Indeed, the executions began to be something of a religious spectacle, one of which Boxer describes as follows:

This ordeal was witnessed by 150,000 people, according to some writers, or 30,000 according to other and in all probability more reliable chroniclers. When the faggots were kindled, the martyrs said

sayonara

(farewell) to the onlookers who then began to intone the

Magnificat,

followed by the psalms

Laudate pueri Dominum

and

Laudate Dominum omnes gente,

while the Japanese judges sat on one side ‘in affected majesty and gravity, as in their favorite posture’. Since it had rained heavily the night before, the faggots were wet and the wood burnt slowly; but as long as the martyrdom lasted, the spectators continued to sing hymns and canticles. When death put an end to the victims’ suffering, the crowd intoned the

Te

Deum Laudamus.

{7}

But the Tokugawa Bakufu was not slow to see that such ‘glorious martydoms’ were not serving the desired purpose; and bit by bit death was preceded by torture in a tremendous effort to make the martyrs apostatize. Among these tortures was the ‘ana-tsurushi’ or hanging in the pit, which quickly became the most effective means of inducing apostasy:

The victim was tightly bound around the body as high as the breast (one hand being left free to give the signal of recantation) and then hung downwards from a gallows into a pit which usually contained excreta and other filth, the top of the pit being level with his knees. In order to give the blood some vent, the forehead was lightly slashed with a knife. Some of the stronger martyrs lived for more than a week in this position, but the majority did not survive more than a day or two.

{8}

A Dutch resident in Japan declared that ‘some of those who had hung for two or three days assured me that the pains they endured were wholly insufferable, no fire nor no torture equalling their languor and violence.’

{9}

Yet one young woman endured this for fourteen days before she expired.

From the beginning of the mission until the year 1632, in spite of crucifixions, burnings, water-torture and the rest, no missionary had apostatized. But such a record could not last; and finally the blow fell. Christovao Ferreira, the Portuguese Provincial, after six hours of agony in the pit gave the signal of apostasy. His defection being so exceptional might seem of little significance; but the fact that he was the acknowledged leader of the mission made the shock a cruel one—all the more so when it became known that he was collaborating with his former persecutors.