Silent House (16 page)

“Where were you?” he shouted.

I didn’t say anything, just listened to the crickets. We were both silent for a bit.

“Come on, get in here, come on!” said my father. “Don’t just stand out there.”

I came in through the window. My father just stood there in front of me, giving me his look. Then he started again: Son, son, why don’t you study, son, son, what are you doing out in the street all day long, and so on. Suddenly I thought: Why does my mother put up with this whiny guy? I’ll go wake my mother and have a talk with her, and the two of us will leave this guy’s house. Then I thought about how upset my father would get and I got stressed. You’re right, it’s my fault, I did spend the whole day wandering in the street, but don’t worry, Dad, tomorrow you’ll see how I can work. If I’d actually said that, he wouldn’t have believed me anyway. In the end he stopped talking and was just looking at me, angry, and since he seemed like he was about to cry, I went straight to my room and sat down at my table, as if to say, look, I’m studying math, don’t be upset, Dad, okay? Finally, I had to close the door. But my lamp was on, let him see the light from under the door, see, I’m working. He was still muttering to himself.

A little later, I could no longer hear my father’s voice, and I was curious, so I slowly opened the door and looked: gone to bed. They want me to be working while they have a nice sleep. Okay, since a lycée diploma’s so important, I’ll work. I’ll work all night without sleeping, see, I’ll work so much that my mother will be upset in the morning, but I know that there are much more important things in life. If you like I’ll tell you, Mother: Communists, Christians, Zionists, you know what I mean, Masons, who are infiltrating this

country—do you know what Carter and the pope talked about with Brezhnev? If I told them they wouldn’t listen, if they listened they wouldn’t understand … So anyway, I said, let me start on his math before I get myself all worked up.

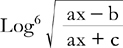

I opened the book, but I got stuck because of that goddamned logarithm. Yes, we write it “log” and we say that a log(AB) = AlogB. This is the first rule, but there are others. The book calls them theorems. First I copied them all nicely in my notebook. Afterward it felt good to look at how I’d written it all out neatly. I’ve written four pages, I know how to work. So that’s all there is to this stuff they call logarithms. Let me do a problem, too, now, I said. Take this logarithm, it says:

Okay, I’ll take it. Then I looked at what I’d written in my notebook again, a long time went by, but I still couldn’t figure out what I was supposed to divide or multiply by what and what I was supposed to reduce with what. I read it again, I just about memorized it, how did they solve the model problem, I looked at that, too, but the weird symbols still weren’t speaking to me. I was really

annoyed

, so I got up. If I had a cigarette right now, I’d smoke it. I sat down again and picked up my pen and tried again, but my hand just made doodles on the page. Nilgün, look at what I wrote on the edge of the page a little later:

To you my heart does not incline

You’ve made my mind decline

Then I worked a little more, but it was no use. I thought a little more about it: What good is it to know the relationships between all these logs and square roots. Let’s say that one day I’m doing government business or I’m so rich that I can only calculate how much

money I have by using these logarithms and square roots: on that day, would I be so stupid as not to even think of hiring some little accountant to do these calculations for me?

I put the math aside and opened up the English, but I was already in a bad mood: I thought, God, give that Mr. and Mrs. Brown what they deserve; the same pictures, the same cold smug faces on people who know everything and do everything correctly, these are the English, they have ironed jackets and ties, their streets are perfectly clean. One sits and the others stand and meanwhile they keep on putting a matchbox that doesn’t even look like one of ours on, under, in, and next to a desk. I had to memorize when it was

on

or

in

or

under

or—what was the other one—otherwise the lottery agent snoring away in the other room would beat himself up, because his son wasn’t studying. I covered them with my hand and memorized them, staring at the ceiling, I memorized them and then, when I couldn’t take it, I grabbed the book and threw it at the wall. Damn it to hell! I got up from the table and looked out the window. I’m not the kind of person who’s just going to put up with stuff like this. I felt a little better as I looked out from the corner of the garden at the dark sea and at that lighthouse on the island with the dogs, the one that blinks on and off all alone in the darkness. The lights from the neighborhood down below were out; there were only the streetlamps and the lights of the glass factory that made deep rumbling noises, and then a red light from a silent ship. The garden smelled of scorched plants, there was a faint smell of earth and of summer, and it was silent, except for the crickets, bold crickets who reminded us of their existence in the pitch-black darkness of the cherry orchards, the far hills, lonely corners, in the coolness of olive groves, and under the trees. I thought I might have also heard the frogs from the muddy water over by the Yelkenkaya road. I’m going to do a lot of things in life! I thought of it: wars, victories, the fear of defeat and the hope for glory, the kindness I would show the poor things and others whom I would save on that road we would take in this heartless world. The lights in the neighborhood below were dim: they were all sleeping, all asleep, having

their dumb, meaningless pathetic dreams while up here, awake above them all, it’s just me. I love to live and I hate sleeping: there are so many things to do.

I stepped away from the window, and realizing that I wasn’t going to study anymore, I lay down without taking my clothes off. I’ll get up and start again in the morning. I told myself, actually, over the last ten days I’ve done enough English and math. I also said that soon the birds will start singing in the trees, and you’ll go to the beach because you think no one’s there, Nilgün. But I’ll come, too. Who could stop me? At first I thought I wouldn’t be able to sleep and that my heart would strangle me again, but then I realized that I was falling asleep after all.

When I woke up the sun was on my arm, and my shirt and pants were damp with sweat. I got right up and looked: my mother and father weren’t up yet. I went into the kitchen. As I was eating bread and cheese my mother came in:

“Where were you?”

“Where was I supposed to be, I was here,” I said. “I studied all night.”

“Are you hungry?” she said. “I’ll make some tea, you want some, son?”

“No,” I said. “I’m going.”

“Where are you off to at this time of day, with no sleep?”

“I’m going for a walk,” I said. “It’ll do me good. After that I’ll come back and study again.” Just as I was going out, I could see she was starting to feel sorry for me. So I said, “Hey, Mom, can you give me fifty liras?”

She looked a little hesitant before she said, “So. What are you going to do with the money this time? Okay, never mind! Just don’t tell your father!”

She went inside and came back: two twenties and a tenner. I thanked her and went to my room, put my bathing suit on under my pants, then went out the window so I wouldn’t wake up my father. I turned and looked back, and my mother was looking at me from

the other window. Don’t worry, Mom, I know what I’m going to be in life.

I walked down the asphalt way. Cars passed me, going uphill quickly. Guys with ties, their jackets hanging inside the car, as if they couldn’t see me as they raced off to Istanbul at one hundred kilometers an hour to make deals and cheat one another. I don’t care about you either, gentlemen, with your ties and cuckold’s horns!

There was nobody on the beach yet. Since even the ticket seller and the watchman hadn’t arrived, I went in for free, and carefully, so as not to get sand in my sneakers, I walked all the way over to the rocks where the beach ended and the wall of a house began, planting myself where the wall didn’t get the sun. I would see Nilgün from here when she came in the gate. I could see the bottom of the calm sea: there were wrasse fish riding and turning in amid the seaweed. The careful gray mullet dashed away at the slightest movement. I held my breath.

A long while later, someone with a mask and flippers aimed his gun in the water, going after the mullet. I get so annoyed with these jerks going after the mullet. Then the water cleared again and I saw the mullet and the rockfish. After that, the sun began to beat down on me.

When I was little, and there were no other houses around here except for their strange silent house and our house on the hill, Metin, Nilgün, and I would come here and I would go into the water halfway up to my knees and we’d wait, trying to catch wrasse or blenny fish. But all we ever caught was a rockfish: Throw it away, said Metin, but it had eaten my bait, I’m not going to just throw it away, I’ll put it in my box, and Metin would mock me! I’m not cheap, I would say. Maybe Nilgün would hear me and maybe she wouldn’t. I’m not cheap, I would say, but I am going to make that rockfish pay for the bait. Metin put a screw nut on the end of his rod instead of a lead weight and said, look at that, Nilgün, he’s so cheap, he’s keeping it! Guys, Nilgün would say, just throw those fish back in the sea again, okay? It’s a shame. I know it’s hard to be friendly with them. But

you can make soup from rockfish, you just put in some potatoes and onions.

Later I watched a crab. Crabs are always concentrating and thoughtful, because they’re always up to something. Why are you waving your leg and your claw around like that, now, little guy? It was like all these crabs knew more than I did. They’re all old know-it-alls, from birth. Even the soft little baby ones with the pure-white bellies are all like old men.

Then the surface of the water shimmered and you couldn’t see the bottom, until the crowd slowly started to go in and out and it got really cloudy. I took a look over at the gate and I saw you, Nilgün, coming in with your bag. You came over toward this side of the beach and you walked straight toward me.

She came closer and closer and then she stopped and took off the yellow dress she had on and just as I was saying, oh, a blue bikini, she had spread her towel on the ground and stretched out on it, suddenly disappearing from view. When she took a book out of her bag and started to read, I could see her hand holding the book in the air and her head.

I was sweating. A long time went by, and she was still reading. Then I splashed some water on my face to cool off. Another long period of time went by and she was still reading.

What if I just go and say, Hi, Nilgün, I thought I’d go for swim this morning, how are you doing? She’ll get mad, I thought, remembering that she was a year older than me. Better go away now, some other time.

Then Nilgün got up and walked toward the sea. She is beautiful, I thought before she dove in. She swam smoothly, moving away from the shore without looking back at the things she’d left on the beach. Don’t worry, Nilgün, I’m watching your stuff, I said, as she kept swimming out, not bothering to look behind. It looked as if anybody who wanted to could go rifle through her things, but with me keeping an eye out, nothing would happen to them.

Nobody noticed when I got up and went over to Nilgün’s things.

It was okay. Nilgün was my friend. I bent down and looked at the cover of the book lying on top of her bag: there was a Christian grave and two weeping old people and it said

Fathers and Sons

. Underneath the book was her yellow dress, I wondered, What’s in her bag? Careful so nobody would see me, I went through it quickly: a tube of suntan lotion, matches, a key warmed by the sun, another book, a wallet, hair clips, a little green comb, sunglasses, a towel, a packet of Samsun cigarettes, and another small bottle. I looked out and Nilgün was still swimming far off. I was leaving everything just as I’d found it when I suddenly put the small green comb in my pocket. Nobody saw.

I went over to the rocks again and waited. Nilgün came out of the water, quickly walked over pigeon-toed, and wrapped herself in her towel, as though she were a little girl instead of a smart young woman a year older than me. Then she dried off, looked in her bag for something, and, not finding it, quickly put on her yellow dress and left.

I was taken aback for a minute, thinking she had done it to get away from me. I ran after her and saw she was going home. I ran ahead and got out in front of her, and she suddenly turned, which took me by surprise, because now it seem she was the one following me. I turned right, stopping in front of the shop and hiding behind a car tying my shoelaces as I looked: she went into the shop.

I positioned myself on the other side of the road so we would happen to run into each other as we went home. I thought, I’ll take it out of my pocket and show it to her: Nilgün, is this your comb? I would say. Yes, where did you find it? she would say. You must have dropped it, I would say. How did you know it was mine, she would say. No, I won’t say that. You dropped it on the road, I saw you drop it, and I picked it up, I would say. I was waiting under the tree. I was very sweaty.