Silent Witnesses (19 page)

Authors: Nigel McCrery

As a result the police turned their attention to the nearby Royal Seaforth Barracks. It did not take them long to identify a suspect; a private in the Irish Guards by the name of Samuel Morgan had deserted some months before and was already under suspicion regarding an attack on another local woman called Anne McVitte, who had been robbed nearby. Morgan was returned to Liverpool and charged, though only with the attack on Anne McVitte.

The police, meanwhile, decided to investigate his family further. Morgan's sister-in-law admitted to harboring him despite knowing that he was a deserter. When questioned she also said that she had treated the injury to his thumb using a dressing from Morgan's military kit, to which she had applied zinc ointment. She said he had told her that the injury had been caused by barbed wire. She still had some of both the bandage and the ointment left, and she promptly handed these over to the police.

What happened next was very unexpected. Morgan suddenly confessed to the murderâclaiming he only intended to rob Maryâbut denied rape. The investigating officers grew extremely suspicious; Morgan's confession along with the available evidence would be enough to land a conviction. But if he repealed his plea he might be able to get away. They needed more evidence, enough to convince a juryâwith or without a confession.

Further forensic examination of the bandages eventually yielded the results the police were hoping for. When compared, the bandages that Morgan's sister-in-law had handed over exactly matched those found at the scene, as well as those from a third unopened packet found in Morgan's possession. However, military bandages were naturally prevalent across the country during the war, so this alone would not be enough to definitively tie Morgan to the crime scene. Firth began to look at Morgan's clothing, scraping the mud and soil from his clothes. He found that these samples contained traces of manganese, copper, and lead. Examining samples from the blockhouse floor where Mary Hagen's body had been found, he soon discovered that these too contained manganese, copper, and lead. This was strong evidence that Morgan had been at the blockhouse.

Firth then realized something else. While it was true that all the different samples of bandage that he had gathered were an overall match, those obtained at the scene and from Morgan's sister-in-law actually differed from the other samples. They had been double-stitched by hand, whereas the others had been single-stitched by machine. In fact, every other bandage from the barracks had been single-stitched by machine.

If Morgan's bandages had been exactly the same as all the others, his defense might have been able to argue that since

there were thousands of such bandages belonging to thousands of soldiers, there was no way of proving that the one found at the scene came from the same set as those handed over by Morgan's sister-in-law; it might have been dropped by any soldier. However, Morgan had been unfortunate enough to pick up an atypical set of bandages from the barracks store, which very definitely placed him at the scene of the crime.

His trial began on February 10, 1941. As expected, he withdrew his confession, stating that the police had used coercion to obtain it. Nevertheless, his defense was unable to explain away the dossier of evidence that Firth had carefully compiled against him, and he was hanged on April 4, 1941.

When they created the first microscope, those two Dutch lens-makers could not have known the impact their invention would have on the world, nor how vital it would prove to be in aiding criminal investigation. It opened up the possibility of detecting and analyzing minuscule specks of material from a crime scene. Over the years the smallest pieces of trace evidence, even tiny particles of minerals or single hairs, have led to the resolution of some of the largest and most sensational criminal casesâproof, if any were needed, that Locard was right: “Every contact leaves a trace.”

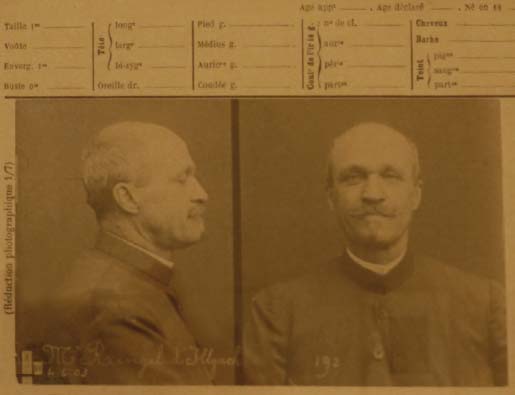

Plate 1 Anthropometric photograph of the artist Ringel d'I11zach, taken by Alphonse Bertillon in 1903. The printed categories at the top demonstrate Bertillon's careful notation of facial features and their relative size.

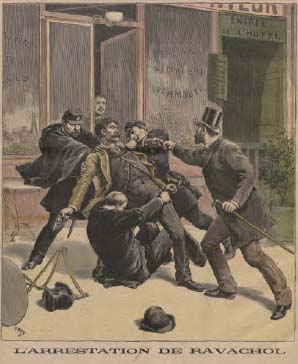

Plate 2 The cover of

Le Petit Journal

from April 16, 1892, illustrating the difficulty with which Ravachol was eventually arrested.

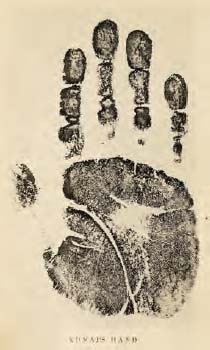

Plate 3 Sir William James Herschel (1833â1917) took handprints from Bengali solders to try to prevent fraudulent pension withdrawals. This was instrumental in showing that fingerprinting could be used as a reliable means of establishing identity.

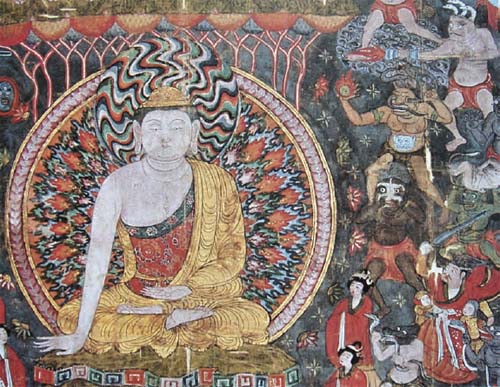

Plate 4 Detail from a tenth-century banner from Dunhuang which appears to show the first depiction of both “fire-lances” and early grenades. Demons can be seen at the top right of the image, brandishing the weapons at a meditating Buddha.

Plate 5 A flintlock mechanism, showing both the spring-loaded cock and the frizzen it struck, which created sparks to ignite the gunpowder.

Plate 6 In the early twentieth century, blood analysis began to play a significant role in criminal investigations. Once Paul Uhlenhuth had devised a test to distinguish animal blood from human, killers like Ludwig Tessnow were no longer able to rely on the defense that bloodstains on their clothes were of animal origin. Tests for dried blood soon followed, and eventually tests to determine blood group. Blood analysis remains at the heart of many forensic investigations today.

Plate 7 The examination of blood spatter patterns can be extremely helpful in determining the events that took place during a violent crime. Dr. Paul Leland Kirk once remarked that “no other type of investigation of blood will yield so much useful information as an analysis of the blood distribution patterns.”

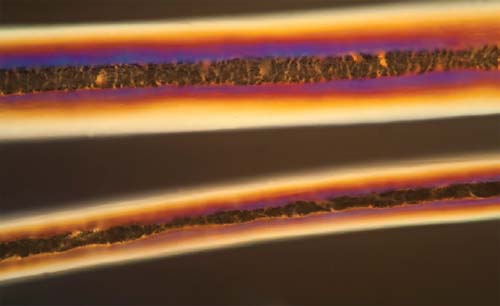

Plate 8 Two human hairs are compared underneath a microscope. As early as 1909, the close inspection of trace hairs on the body of Germaine Bichon was enough to establish that the suspected killer, Madam Bosch, had indeed been present at the scene.