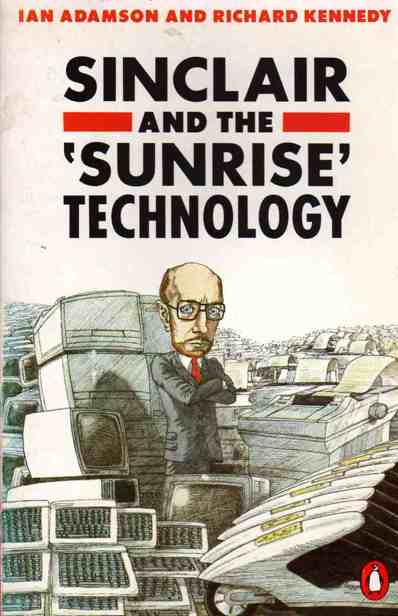

Sinclair and the 'Sunrise' Technology: The Deconstruction of a Myth

Read Sinclair and the 'Sunrise' Technology: The Deconstruction of a Myth Online

Authors: Ian Adamson,Richard Kennedy

Tags: #Technology & Engineering, #Business, #Economics, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Electronics, #Business & Economics

PENGUIN BOOKS

SINCLAIR AND THE ‘SUNRISE’ TECHNOLOGY

The Deconstruction of a Myth

Ian Adamson and Richard Kennedy

OCR’d by Ken D

Penguin Books

Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

Viking Penguin Inc., 40 West 23rd Street, New York, New York 10010, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Limited, 2801 John Street, Markham, Ontario, Canada L3R 1B4 Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

First published 1986

Copyright © Heresy Promotions Ink, 1986 All rights reserved

Made and printed in Great Britain by

Richard Clay Ltd, Bungay, Suffolk

Filmset in Monophoto Sabon by

Northumberland Press Ltd, Gateshead, Tyne and Wear

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

This book is dedicated to the memory of Giordano Bruno, Jacques de Molay, Domenico Scandella and all the others, plus, lastly, ‘in order to establish certain principles’, Anarcharsis Clootz.

‘I am the Daughter of Fortitude and ravished every hour from my youth, for behold, I am Understanding, and Science dwelleth in me.’

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks are due to Edward and Nicola for being accommodating far beyond any reasonable expectations, and to our editor for encouragement and extreme tolerance.

We would also like to take this opportunity to thank all the people and organizations who assisted in the gathering of information for the book, especially Cherril Norrie and the VNU library, Frances Cairncross at the Economist, Dave Tebbutt, and Jane Bird of the Sunday Times.

Finally, thanks and much more to Gillian and Fran, without whom...

INTRODUCTION

I rather like those books where each chapter begins with a quotation.

Samuel Johnstone

Why does Sir Clive Sinclair merit our undivided attention? Why devote an entire book to the examination of one man’s enterprise? Britain has produced more seductive personalities than Sir Clive and hordes of anonymous entrepreneurs more successful in business. So why bother chronicling the oscillating development of the Sinclair empires?

The obvious answer to all the above questions is that Clive Sinclair is a household name in the UK and a businessman of international repute. For millions of home-computing hobbyists the ‘Uncle Clive’ persona and the Sinclair logo were synonymous with the microboom of the early 1980s. As guru to a new generation of computing enthusiasts, Sinclair and his ZX range of micros took the high streets by storm, putting the home into home computing. For those bitten by the computing bug the inside story of the Sinclair microrevolution can now be told!

However, why should ‘England’s thin, unprepossessing inventor’ (as the Wall Street Journal describes him) be a familiar figure even among those who don’t know one end of a microcomputer from the other? His commercial activities over a quarter of a century have linked the man and his products to the hope of economic progress through individual entrepreneurship. Harnessing high technology in the interests of the small business, Sir Clive’s individual style of management has been presented as the heroic endeavour of an enterprising David taking on the Goliaths of industry. For a time, ‘Thatcher’s favourite entrepreneur’ was seen as one of the few businessmen with the flair and imagination to challenge the Japanese domination of the consumer electronics market. Unfortunately, initial success was followed by a combination of marketing and managerial mistakes that has taken the shine out of this ‘sunrise’ industry. As we shall see, the tarnished history of Sinclair’s endeavours tends to repeat itself, revealing the weaknesses inherent in the Sinclair style.

The fall of this modern-day Daedalus calls into question the validity of the popular perception of Sir Clive and his companies. What the public has is a view that is essentially a myth. The fact that in a popular survey Uncle Clive can be nominated as one of the top ten scientists of all time reveals the power of this myth. Regrettably, while one might be able to shrug off the general woeful ignorance of the populace and treat it, as Sir Clive does, as a mindless horde of potential consumers, the virus of mythopoeia has struck deeper. Listen to the words with which one of the new centres of learning in this country proposed as an honorary Doctor of Science the man ‘whose qualities, as inventor and educator, we [the University of Warwick] attempt to emulate... His sense of what society will need, of what the consumer will want, and of what technical problems can be overcome, stems from a humane and well-balanced personality...’ And this is no isolated instance. The Royal Society presented Clive with the Mallard Award, supposedly for ‘outstanding contributions to the advancement of science or engineering or technology leading directly to national prosperity in the UK’, because of ‘his entrepreneurial and innovative inventions of pocket calculators, personal computers and small television tubes of flat design ... his brilliance as an entrepreneurial and innovative inventor’

This sort of hyperbole is less than accurate, as will be seen in the course of our text. While writing a review and assessment of Sir Clive’s career we found ourselves unwittingly engaged in an exercise of demystification. Sir Clive undoubtedly has talents, but they are not those popularly ascribed to him. Apparently, as a consequence of the Snarky Principle (i.e., ‘What I tell you three times is true’), the attributes of ‘inventor’, ‘innovator’ and ‘entrepreneur’ have hitherto resisted erosion by reality.

In terms of ‘invention’ Clive produces primarily ideas for products rather than conforming to the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition, ‘One who devises or produces something new by original contrivance’. The definition may apply to workers on the Sinclair R&D team, but there is little evidence to show that Sir Clive himself plays such a role. ‘Innovator’ is more like it - one who ‘brings in or introduces novelties’ (OED) - but the head of Sony, for example, is not styled thus when a product like the Walkman is produced. So why Sir Clive?

We came round to the view that it is the paucity of Sir Clive’s product ideas rather than their multiplicity that should be a source of wonder. While other unsung inventors produce such things as the computerized running shoe (marathon man Clive might have been expected to come up with that one!), the fingertip pulse monitor, the pocket computer database and a plethora of microchip-dependent products sold by mail order and generating quiet profits for their producers, Sir Clive puts his greatest energies into his obsessions, as witness the twenty-year pocket-TV saga. Market-motivated corporate effort allied to true inventiveness could produce a variety of products, ensuring a broad product base, avoiding the problems of a company overly dependent on a single product area for its cash flow and generating enough resources to allow the pursuit of personal fetishes via corporate R&D.

So what lessons can be gleaned from the Sinclair story? Well, far from promoting the entrepreneur as a necessary good, the floundering career of Clive Sinclair offers valuable (if not especially encouraging) insights into the dangers of relying on small businessmen to resolve the evils of unemployment and inflation, which are the defining elements of the commercial environment they inhabit and from which they profit. Far from smothering reality with a cosmetic veneer of progress, can this be an example of the received truth that the individual pursuit of wealth precipitates only intermittent commercial success coupled with short-term employment, the accumulation of personal wealth and the realization of personal whim? It is not the solution to unemployment. It does not address the structural weaknesses of moribund capitalism. Instead the ‘small-business’ solution is a short-term expedient and a historical regression. Although by no means morally or even pragmatically defensible, conventional corporate enterprise depends on the experience, endeavour and imagination of an entire workforce in the creation of a commercially viable commodity. It is inclined towards long-term employment because its operational structures are informed and determined by the relationship between a historically defined productive capacity and the developmental requirements of future products. In other words, stable, long-term corporations (certainly those profiting from a workforce with a solid union base), examining a product whose profitability requires the replacement of existing productive structures with a cheaper workforce, tend to dispose of product rather than employees. In contrast, the profitability of the ‘new-style’, hi-tech enterprise à la Sinclair relies ultimately on the surplus value generated by a cheap workforce in the creation of products developed by a well-paid technical elite. Such a structure is unstable by definition. The composition of the technical elite is determined by the specific parameters of the commodities that are under development. The manufacturing resources are purchased via a subcontractor and selected according to the availability of capital equipment, and/or ‘development’ grants, and/or the general malleability of the workforce - which is directly proportional to the threat of unemployment. (It is no coincidence that the last generation of Sinclair products was developed in affluent Cambridge but manufactured in impoverished regions of Scotland and Wales.) The valorisation of the technical team’s efforts and the job security of the manufacturing force are contingent largely on the commercial potency and practical viability of the entrepreneur’s vision.

Sinclair’s personal success and fortune do nothing to support the view that Britain’s hope of economic recovery lies in the prosperity of the entrepreneurial minority celebrated by Thatcher’s Conservatives (and financially bolstered by the rest of the nation). Far from offering a hope for the future, Sir Clive’s millions and his corporate failures merely confirm that there is money to be made from exploitation of the pernicious symptoms of economic decline.

That individuals can profit from high unemployment and the cheap raw materials available in a contracting component market is hardly an earth-shattering revelation. Sinclair’s failure to live up to the political role to which he was assigned will surprise only the most literal devotees of Thatcherite dogma. Thus we’ve chosen to resist expounding the obvious or attempting to enlighten those hopelessly blinkered by ideology. Our central concerns emerge as the presentation of a detailed case history that reveals the inherent fallibility of the ‘entrepreneurial solution’ to economic crisis and the durability of media-generated mythology.

When we interviewed the man himself we found Sir Clive courteous, accommodating and charming, leaving us with little in the way of a personal axe to grind. If we were looking for a ruthless entrepreneur to expose to the pressures of gutter journalism, Clive Sinclair would come pretty low on our list of viable victims! This said, it soon became clear to us that the public’s image of Clive Sinclair is almost entirely a product of public relations. At the peak of his success it was Sinclair mythology that bestowed a seal of credibility on his companies’ products, promised a technological future based on research that was tethered to the economies of high-street manufacture and promoted business methods that were embraced by the state but discredited by practice.

The myths surrounding the man may be insignificant in their own right but merit close analysis when they are used to validate destructive economic strategies. However, it must be admitted that the more we learned about Sir Clive and his businesses, the more determined we became to set the record straight. The Sinclair PR machine has undoubtedly contributed to the commercial success of a handful of products, which in turn has played an important role in promoting Sinclair’s image as inventor, innovator and all-round hi-tech don. Sinclair Research’s microcomputer products provided the hi-tech industries with a popularist figurehead who for a while proved acceptable to both the City and the consumer. It’s impossible to overstate the value of such a commodity.

Throughout the 1970s and the first half of the 1980s the commercial realization of technological innovation in the UK was impeded by the inability of investors to keep abreast of the increasingly sophisticated demands of the consumer (whether the consumer be Joe Public or the Ministry of Defence); ignorance precluded an informed assessment of market potential. Sir Clive’s personal success story encouraged financial speculation in such markets; his corporate failures confirmed the City’s worst suspicions. In other words, one of the most damaging consequences of Sinclair’s brief reign as the high priest of hi-tech was that his downfall called into question the viabilities of the new technologies as investment options.