Singing Hands (21 page)

Authors: Delia Ray

Daddy shook his head sleepily. "Not this week. His students begin arriving tomorrow, remember?"

"Oh, that's right." I nodded.

I tapped Daddy's arm again. "What about next weekend?"

He gripped the steering wheel and finally himself from his comfortable spot, smiling wanly at my stubborn questions. "Maybe so. But I won't even be in Birmingham next weekend. I'll be preaching in Jasper. Although," he added slowly, with a hint of mystery in his voice, "I don't think I'm the one Mr. Vincent really wants to visit."

I cocked my head to one side. "What do you mean?"

"I think he'd like to see Grace Homewood."

Just like that, Daddy said it, as if he was commenting on the weather.

I couldn't stop my eyebrows from shooting upward. "Really?" I asked, as if I had never heard of such a notion. "How do you know?"

"I knew them both as students, and later, when they started working at ASD. They were sweethearts once."

I leaned forward, my voice hushed. "What happened?"

Daddy shook his head. "It was sad. Grace's parents didn't want them to be together. They were afraid that if their daughter married a deaf man, their grandchildren would be deaf, too." He shook his head again. "For some hearing people, that's too frightening a prospect."

"You knew all along?" I cried. "That they loved each other? Couldn't you have done something? Something to change her parents'â"

Daddy held up his fist, twisting it back and forth in a firm sign for "no." "It's not always my place to step in. Besides," he added, crossing his hands over his heart, "true love has a way of working out on its own, with or without a minister's help."

With that pronouncement, my father tipped his head back against the seat and quickly drifted off to sleep. I gazed over the dashboard toward the bean field. This time I wasn't the least bit impatient during Daddy's catnap. My mind was too busy spinning far-fetched possibilities round and round.

Back at home that evening, the possibilities didn't seem quite so far-fetchedâespecially after Miss Grace nodded hello and honored me with a tiny smile of forgiveness when we happened to pass on the stairs. After dinner, while Mother and Daddy lingered at the table signing, I wandered up to my father's office and sat at the window in his swivel chair. Across the hall, Mrs. Fernley was playing an opera piece I had never heard before. As I listened to the soprano's voice floating through the third floor, I looked down and imagined the magical scenes of my own little opera playing out on our shadowy driveway below.

I could see it so clearly: a taxicab pulling into the streetlamp's circle of light and Mr. Vincent striding up the walk with the heart-shaped box tucked in his pocket, ready to retrieve that missing piece.

And I could see my sisters as they arrived home from Texas. I would run out to the driveway to greet them. I would hug Nell, and Margaret, too, and resist the temptation to blurt out my latest news: that I had actually directed a signing performance at the Jubilee, and as a reward, Mother had invited me to come back to Saint Jude's and join the deaf choir on Sunday mornings.

And I could see the Packard pulling out of our driveway again and again during the busy falls and winters and springs to come. But from now on, at least once a month, I would be at Daddy's side on the front seat, on my way to Talladega to visit Abe and my other new friends at the Alabama School for the Deaf.

And far beyond the glow of the streetlamp, I could see Vulcan's torch shining over Red Mountainâwhat else but a brilliant and hopeful shade of green?

All right,

I thought.

I'm ready.

I spun around in Daddy's swivel chair, wheeled back to his desk, and rolled a clean sheet of paper into the Smith Corona. This time I didn't need the Funk and Wag or any other dictionary to finish my word-list assignment for Mrs. Fernley. I was ready to define "integrity" all on my own.

My mother once told me a story that helped me understand some of the complexities of growing up as a hearing child of deaf parents. She was sitting in class in sixth or seventh grade when she happened to drop her pencil on the floor. Joe Milazzo, who was the object of all the girls' secret crushes and would one day be voted best-looking boy in the senior class, reached down and returned her pencil. Without thinking, my mother made the sign for the words "Thank you," touching the fingertips of her right hand lightly to her lips.

Joe turned a bright shade of red and grinned at her in utter surprise. Up and down the rows of desks, her classmates were grinning, too. Everyone thought that shy Roberta Fletcher had just blown a kiss to none other than Joseph Milazzo. My mother thought she might die of mortification.

Over the years I asked my mother many questions about the Fletcher family. She poured forth one tale after another about life in this colorful southern household with a deaf father who worked as a traveling minister, a deaf mother who took on the burdens of his far-flung congregations, four lively hearing children, and a parade of eccentric ladies who rented the extra bedrooms to help the family make ends meet. From these stories, this novel was born.

While many scenes in this book are borrowed straight from my mother's recollections, others have been conjured from my imagination. Instead of the four siblings of the Fletcher family, I decided to grace the Davis family with three daughtersâmainly because I have three daughters of my own and have become well-acquainted with the joys and sorrows of the sisterhood triangle.

Perhaps the character in the book who is shown in the truest light is Reverend Davis, whose portrayal is based on my grandfather, Robert Capers Fletcher. Whenever I think of summer visits from Pop, I picture him sitting next to me at our kitchen table, teaching me how to sign the alphabet. He never seemed to tire of guiding me through those twenty-six simple signs. He lingered fondly over each letter, demonstrating first and then smiling as he shared clever hints to help me recall the proper hand positions. "Pretend you're picking up a feather," he instructed when we came to the letter F. "That's itâ

F

for feather." For G, it was always, "Hold your hand like this, like you're shooting a gun. Remember G for gun."

After several practice sessions with Pop, I could fly through the alphabet without any reminders. "Phew!" he would exclaim and shake his head as if he had never encountered such speed and dexterity.

Once he was satisfied with my fingerspelling, Pop began to teach me signs for words, always adding an entertaining explanation of what the origins of the gesture might be. For example, to make the sign for "girl," he explained, you brush your thumb along the side of your cheek, representing the bonnet strings that girls in the olden days used to tie under their chin.

Years later, when I introduced my grandfather to the man I would many, barely ten minutes had passed before Pop seated my future husband at that same kitchen table to slowly and patiently teach him the sign for A, then

B,

then C....

I laughed at the familiar sight, but I wasn't surprised. I had always known my grandfather was a natural-born teacher. What I didn't know, until I began the research for this book, was how vast the scope of his teachings had been.

Like the character of Reverend Davis, my grandfather worked as an Episcopal missionary to the deaf, traveling by train to organize and preach to congregations spread across nine states. For twenty-five years, with the help of his faithful wife, Estelle, he kept up a relentless pace of travel, returning to Birmingham for just one week a month to tend to the needs of his family and his home church, Saint John's Church for the Deaf (fictionalized and renamed Saint Jude's in this book). The constant travel took its toll. Chronic stomach ulcers and a severe bout of pneumonia finally forced my grandfather to confine his mission work to the state of Alabama.

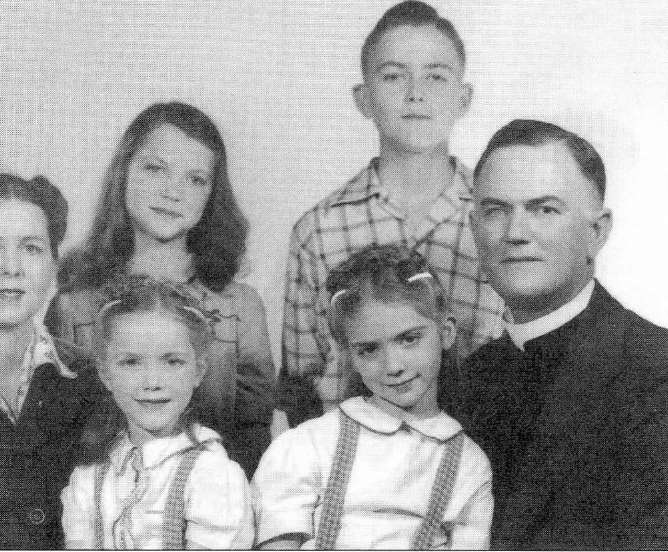

The Fletcher family's real-life experiences inspired many of the events in this novel. Pictured above are the Reverend Robert Fletcher and his wife, Estelle, and their four childrenâLouise and John (at back), with their younger sisters, Georgianna (left) and Roberta (right) in matching outfits.

From the 1930s to the early 1970sâa time when society ignored and often shunned "the handicapped"âReverend Fletcher's services provided a bright ray of light in the lives of hundreds of deaf church members, both white and black. They eagerly awaited his arrival each month, traveling from the nearest cities or isolated country towns to see him deliver his wise sermons, perform baptisms, and conduct marriages and funeral ceremoniesâall in graceful sign language.

While many schools for deaf children were teaching generations of pupils that it was shameful to sign and that they should disguise their disability by learning to speak like hearing people, Reverend Fletcher taught his students to be proud of their unique language. He mesmerized his audiences with his vivid signed storytelling. But most of all, his mission centered on bringing deaf people out of the shadows and helping them move freely between the worlds of the hearing and the deaf. At heart, my grandfather was a matchmaker, delighting in pairing those he met during his travels with the perfect mate, a steady job, or an affordable home.

Pop passed away in 1988. What I wouldn't give for the chance to sit with him once more at that old kitchen table and show him how smoothly I can sign the alphabet. But thankfully, though both my grandparents are gone, there are still hands singing everywhere to remind us of the rich gifts that they and their fellow pioneers in the deaf community left behind.

I would like to thank Douglas Baynton for his generosity in providing insight about deaf culture and for his sensitive and expert critique of the original manuscript for this book. Thanks are also owed to Lynn Edge and Garland Reeves for their tours of landmarks and their gracious answers to my flurry of questions related to Birmingham history, and to the Reverend Jay Croft and the members of Saint John's Church for the Deaf for welcoming me into their lovely sanctuary. Peggy Rupp, Don Veasey at the Birmingham Public Library, and Jean Bergey at Gallaudet University helped to fill in the blanks about important historical details. I am also indebted to Karyn Zweifel and the staff at the Alabama Institute for Deaf and Blind for providing valuable information about the history of the school, as well as Maude Nelson, Olen "the Professor" Tate, and his wife, Agnes, for sharing firsthand accounts of their experiences as students and staff members at the Alabama School for the Deaf.

I am grateful to Virginia Buckley for her editorial wisdom and her faith in this project from the start. And finally, I reserve my profoundest thanks for my mother and "ghost editor," Bobby Fletcher Ray, who dedicated countless hours of phone time, hunting through family archives, and reviving memories to help shape the heart of this book.