Sisters in the Wilderness (10 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

Five weeks into the voyage, the

Anne

was becalmed on the Grand Banks, off Newfoundland. There she sat, sails flapping empty, for three long weeks. By now, Susanna was almost screaming with ennui

.

The Grand Banks fogs were notorious. Another emigrant stuck in a similar fog described how his boat got so lost that he and some crew members jumped into a dinghy to take depth soundings: “During our absence kettles, bells and bugles were kept sounding terrifically on board the good ship, or we should never have found it again, for at twenty yards' distance we lost sight of her. I shall never forget the vast magnifying effect of the mist on the ship, her spread sails, shrouds and cordage. She loomed into sight an immense white mass, filling half the heavens.”

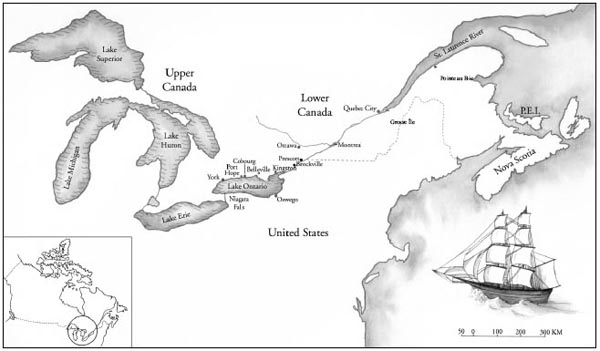

The journey across the Atlantic Ocean, and up the St. Lawrence River into the heart of British North America, took two months.

Supplies were dwindling on the

Anne,

but the dense fog meant that passengers and crew could not see any of the Newfoundland fishing boats strung along the Banks. Other transatlantic vessels managed to augment their rations with fish, either caught by their own crew or purchased from fishermen. “Our fishing goes on with great success,” a colonist who also crossed in 1832 noted in her diary. “The Captain has just succeeded in catching an immense cod-fish [weighing] 40 lbs. Amongst the captures of this day is a Hollybut, 70 lbs weight; we are to have it for dinner.” But there were no monster cod or halibut on the

Anne,

and after close to two months at sea, the steerage passengers were starving and the cabin passengers were down to hard biscuit. Not that Susanna cared; she was wretchedly seasick in the sullen swell. As she clung to the deck rail and stared out into the gloom, she was in limbo, adrift between two worlds, two lives. If only the pebble beaches and crumbling cliffs of the Suffolk seashore would loom out through the fog, rather than icebergsâstark, ghostly and entirely unfamiliar.

In the last week of August, the

Anne

sailed into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. As the sun climbed in the sky and the morning mist cleared to reveal Lower Canada's wild, rocky shores, the Moodies' spirits lifted. Susanna and John stood hand-in-hand at the rail. Susanna was almost overcome by the splendour of the mountains on the north shoreâ“they loomed out like mighty giantsâTitans of the earth, in all their rugged and awful beauty.” She looked up and down the huge waterway: “never had I beheld so many striking objects blended into one mighty whole! Nature had lavished all her noblest features in producing that enchanting scene.” She liked the look of the small whitewashed houses on the

shores close to Quebec City, and the neat churches with their silver tin roofs and slender spires against the backcloth of “dense, interminable forest.” Her excitement blossomed on August 30, when the captain finally dropped anchor off Grosse Ile, the quarantine station thirty-three miles below Quebec City. From the deck of the

Anne,

Susanna watched the bustle of people and boats on the island, heard the sounds of laughter and shouting from the shore and watched the blue smoke from dozens of little cooking fires spiral into the clear sky. After nine weeks of being confined to a ship scarcely more than a hundred feet long, it looked like a “perfect paradise” to her. Visions of fresh bread and butter danced in her head.

This was the first year of operation for the Grosse Ile quarantine station. Before 1832, ships had sailed directly to Quebec City's docks. A surgeon would then come on board for a cursory check for fever among the passengers that might infect the city's residents. But by the late 1820s, the Quebec City authorities were exasperated by the incoming tide of destitute paupers who spread epidemics of typhoid, measles or cholera as soon as they stepped ashore. A few months before the Moodies' arrival, the health authorities of Lower Canada had hastily tacked together some wooden sheds on Grosse Ile and decreed that all vessels must stop there. All steerage passengers were obliged to disembark, to be inspected for disease. Every piece of sheet or blanket that had been used during the crossing had to be taken ashore to be washed; straw bedding was thrown overboard. The sick were herded into the sheds, which looked like animal pens, and held there until they either died or recovered. Within days of its opening, Grosse Ile was known as “the Isle of Death.” Its busiest residents were the coffin-makers.

Susanna Moodie knew nothing of the island's fearsome reputation as she watched the steerage passengers climb into boats to be rowed over to dry land. The Moodie party did not have to go ashore because, as cabin passengers, they were not considered health risks. Only their bedding had to be sent to Grosse Ile, to be washed by their maidservant. Susanna resented being told to stay on the

Anne,

particularly when John

gleefully joined the disembarkation. She was even more chagrined when the captain and her husband returned and told her that they had been unable to replenish their stores, or buy Susanna the loaf of fresh bread they had promised her, because the provision ship from Quebec City had not yet arrived.

Eventually Susanna did go ashore. And she discovered that the perfect paradise was actually a “revolting scene”âa seething mass of shrieking, dirty, half-naked people. Thousands of emigrants jostled each other at river's edge as they tried to wash all their bedding and clothes. Women trampled ragged blankets in the dirty water while yelling at their kids. “I shrank, with feelings almost akin to fear, from the hard-featured, sunburnt harpies, as they elbowed rudely past me.” Even the Scottish labourers who had travelled steerage on the

Anne,

and been perfectly respectful during the voyage, were “infected with the same spirit of unsubordination and misrule, and were just as insolent and noisy as the rest.” It was a rude shock. Her dismay was intensified as she watched a huge, wild-eyed Irishman, flourishing a shillelagh and wearing only a tattered greatcoat, leap over the rocks shouting, “Whurrah! my boys! Shure we'll all be jontlemen!”

Relief had surged through the steerage passengers as they stepped on dry land. They were finally released from the noisy, smelly, dirty claustrophobia of the ship's hold. But Susanna was incapable of empathizing with them. From birth, she had lived in a world of neatly segmented social hierarchies, in which everyone knew the social class they belonged to and regarded other classes almost as separate species. Now, for the first time in her life, there was no invisible membrane between the cabin-passenger gentry and the lower orders. She was looking at a fragmented world of uncertainty. As Susanna struggled to get her bearings in this vision of purgatory, she had her first taste of emigration as exileâexile from the society in which, even though she often felt marginal, she had always known where she belonged. When she tried to express her horror, she sounded impossibly hoity-toity. But it was much more complicated than that: Susanna was trying to protect herself from chaos.

Even in London, Susanna had rarely strayed into the slums of the city's east end or south bank. She had seen poverty, but the closest she had come to scenes of raw humanity, fighting for survival, was in Mary Prince's story, or in Hogarth's series

Gin Lane

, the richly detailed engravings of mass depravity and mayhem that were exhibited in the windows of London's print shops. And so, as she looked around her at Grosse Ile, Susanna's shock was mixed with horrified interest. How could she not recall the description of an uncivilized world she had read in the leather-bound copy of Hobbes's

Leviathan

in her father's library? “No arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.” The sight of Hobbes's words made flesh fascinated Susanna the voyeur. The dark underbelly of the human conditionâmurder, madness, rage, despairâstimulated her imagination, as it would on many occasions in the future. She left Grosse Ile to return to the

Anne

only when she heard that there would be a decent meal of bread, butter, beef, onions and potatoes on board.

Two days later, the

Anne

left the quarantine station behind and sailed towards Quebec City. Safely back on deck, and at a remove from sun-drenched harpies and wild Irishmen, Susanna regained her equilibrium. She relaxed in the sunshine, contemplating spectacular scenery instead of the human terrors of the New World. Only a few months earlier she had gushed for London annuals over imaginary landscapes. Now, stunned by her first sight of the Montmorency Falls and Quebec City perched high on the rocky cliffs, she resorted to the lush vocabulary of Wordsworth and the Romantic poets for the reality: “Nature has lavished all her grandest elements to form this astonishing panorama. There frowns the cloud-capped mountain, and below, the cataract foams and thunders; wood, and rock, and river combine to lend their aid in making the picture perfect, and worthy of its Divine Originator.” She continued to keep reality at arm's length when the

Anne

dropped anchor below the Citadel: she would not step ashore. Ostensibly, this was because cholera raged in the cityâalthough this didn't prevent John Dunbar Moodie,

accompanied by young James Bird, from jumping into a rowboat and disappearing to explore Quebec's winding streets.

The harbour below Quebec City was jammed with ships, and in the middle of the night, disaster struck. A large three-masted vessel, the

Horsley Hill,

with three hundred Irish immigrants aboard, collided with the

Anne

in the dark. There was an ear-splitting crash as the larger vessel's bowsprit came thundering down on the

Anne

, threatening to swamp her. Passengers on the threatened ship swarmed onto the deck, screaming with fear, and Captain Rodgers was immediately surrounded by several frantic women clinging to his knees.

Susanna was lying in her cabin when the pandemonium erupted. Grabbing her baby, she hurried out onto the deck to see what had happened and quickly took in the scene: the towering bulk of the

Horsley Hill,

looming out of the darkness over the

Anne;

the hysterical women immobilizing the captain. She heard the cracks of splitting timbers, the splash of waves, the confused shouting of sailors. Immediately, she rose to the occasion and ordered the women to follow her below deck. Ignoring the foul smell of unwashed bodies and vomit, she made them sit still and pray quietly. By sheer force of personality, and despite her own alarm, she remained cool and in command. “British sailors never leave women to perish,” she told her companions, with apparently unshakable assurance. Until close to dawn, her authority held. The incident must have reassured Susanna that, even in the New World's melting pot of peoples, the natural authority of the educated classes held sway and she could make herself heard.

Although the Traills began their Atlantic crossing a week after the Moodies, they made far better time. After leaving Thomas's relatives in the Orkneys, they went directly to the port of Greenock, outside Glasgow. There Thomas paid fifteen pounds each for his and Catharine's cabin passage to Montreal in a fast-sailing brig, the

Rowley

. The

Rowley

was not a regular passenger ship: its hold was filled with a cargo of rum, brandy and sugar. The Traills' only companions were two young men and the captain's goldfinch.

Catharine had fallen very sick just before embarkation and was unwell for much of the voyage. At one point both the captain and the steward feared that she would die before landfall. But she gradually recovered, and in letters home describing the crossing, her chief complaint about the voyage was boredom. “I can only compare the monotony of it to being weather-bound in some country inn,” she wrote to her mother. She didn't even have Voltaire to fall back on, as Susanna had, let alone a newborn baby. “I have already made myself acquainted with all the books worth reading in the ship's library: unfortunately, it is chiefly made up with old novels and musty romances.”

The most unnerving fact for Catharine was the way Thomas sank into gloom. Thomas was singularly ill-equipped to deal with the voyage. Despite his bookish interests, he had not furnished himself with a library to last six weeks. He had none of John Moodie's interest in catching fish, shooting birds or chatting up the crew and passengers. Instead, he moped. Catharine tried to convince herself that Thomas's low spirits were a typically male response to cramped quarters: “Where a man is confined to a small space, such as the deck and the cabin of a trading vessel, with nothing to see, nothing to hear, nothing to do, and nothing to read, he is really a very pitiable creature.” She resorted to playing the role she had so often played within the Strickland family: the resilient optimist, who raised everybody's spirits. When a long-faced Thomas started pacing the deck, she rose from the bench where she was sitting and sewing and walked alongside him, her arm linked through his. She enthused about all their plans for the future and the excitements that awaited them in Upper Canada. But there was a hard-headed realist underneath the Pollyanna cheerfulness. She realized that this was an inauspicious start to their marriage and emigration. She confided to her mother that the plans she had described with such gusto “in all probability will never be realised.”