Sisters in the Wilderness (19 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

At the same time that Britain was turning its back on its North American possessions, tensions were emerging within the colony itself. The interests of the governed were visibly diverging from those of the governors.

The titular ruler of Upper Canada was the lieutenant-governor, a well-born Englishman (usually the possessor of a title, several military honours or at the very least a coat of arms for his carriage) sent by Westminister to Toronto to run the colony's affairs. The actual governors were his local advisersâthe clergymen, officers, officials and landowners of the Family Compact whose idea of government was entirely feudal. Members of this local oligarchy were linked by blood, marriage or at least allegiance to the Church of England. Comfortably ensconced in their impressive stone mansions in Toronto, members of the Family Compact dominated the judiciary, the Executive Council and the Legislative Council (neither of which was elected) and much of the House of Assembly (the elected lower house, which was virtually powerless). They dispensed favours to their friends and directed British policy to their own advantage.

The Traills and the Moodies would have loved to belong to this exclusive élite of families like the Boultons, Jarvises and Powells. They felt connected to them by virtue of their education and background, and they yearned to be recipients of their patronage. Either Thomas Traill or John Dunbar Moodie would have been ecstatic to get his hands on a government job like local land registrar, which gave its holder an income. Thomas Traill was overjoyed when he was appointed a justice of the peace. Even though remuneration was derisoryâa small proportion of

the fees charged for performing marriages or the fines levied for minor crimesâthe office bestowed on its holder a dab of prestige.

However, neither the Moodies nor the Traills had the wherewithal to join the exalted ranks of bigwigs in the colonial capital. Both couples were stuck in the backwoods because that was where they could get free land. Like everybody else who was roughing it in the bushâfrom rude Yankees to Anglo-Irish gentlefolk, from Irish paupers to Scottish labour-ersâthey were the governed. And like the rest of the backwoods settlers in the late 1830s, the sisters and their husbands faced mounting problems: crop failures, a shortage of money, a slow-down in immigration, struggles with inadequate transportation facilities.

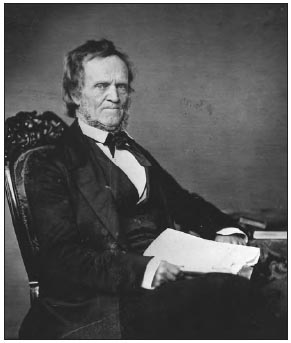

A brilliant demagogue, William Lyon Mackenzie (1795â1861) was a hero in the backwoods, but a thorn in the flesh of Toronto's Family Compact.

By now, the diminutive and hot-tempered Scottish-born journalist William Lyon Mackenzie had emerged as the backwoodsman's champion. Part hustler, part prophet, “Little Mac” had been galvanizing opposition to the Family Compact since the early 1820s, first as the outspoken editor of

The Colonial Advocate

and then as an elected member of

the legislature of Upper Canada. In more recent Canadian history, only Newfoundland's Joey Smallwood can match Mackenzie for populist wizardryâdemonic fluency, fierce energy, fearlessness against the odds and an ability to fill the air with honey and gall. By the time the Traills and Moodies were settled in Douro Township, Mackenzie was busy inflaming the ragged (and often illiterate) backwoodsmen with his passionate Tory-bashing and his stinging criticism of the Toronto nabobs. Speaking from schoolhouse steps or the back of farm carts, he ranted about dishonest officials, corrupt clergy and lace-cuffed place-seekers. He pointed out that Upper Canada was a stagnant backwater compared to the United States, where newcomers had a say in their country's future and easy access to land. On the main streets of every small town in Toronto's hinterland, he accused the Family Compact of ruling Upper Canada “according to its own pleasure” and committing “acts of tyranny and oppression.” His voice shrill with indignation, and his red wig repeatedly sliding off his bald head, he made personal attacks on his political enemies. He insisted that people like Henry Boulton, the Attorney-General of Upper Canada, and John Beverley Robinson, Chief Justice, “surround the Lieutenant-Governor, and mould him like wax to their will.”

The Traills and Moodies had plenty of reasons to agree with the substance of Little Mac's tirades. They had firsthand experience of the sluggish development of the backwoods. But they were so blinded by their social prejudices and eagerness to cling to “establishment” values that they failed to see that Little Mac was talking about their own plight. They couldn't see that the colonial administration was impervious to problems faced by families like theirs. They didn't understand that their own community would never thrive, or their own land rise in value, unless the colonial government stepped in to encourage settlement and invest in better transportation systemsâmeasures the Family Compact had no desire to initiate.

To people like Traill and Moodie, William Lyon Mackenzie was a dangerous radical and a troublemaker who challenged all their most

dearly held principles of social order. Another gentleman farmer in the Peterborough region, John Langton, spoke for his ilk when he dismissed Mackenzie as a “little factious wretchâ¦. He is a little red-haired man about five foot nothing, and extremely like a baboon.” Mackenzie's followers, in the considered opinion of John Moodie, were “under the influence of the most odious selfishness.” Moodie was too busy detecting a strain of republicanism in the Radicals' demand for representative government to appreciate Mackenzie's diagnosis of the colony's problems. Little Mac's followers were, in Susanna's words, “a set of monsters,” traitors to the British flag and “enemies of my beloved country.” And the agitation of the Radicals meant a further drop in immigration to Upper Canada from the mid-1830s, with jarring consequences for life around Peterborough.

The legacies to Susanna and Catharine had been substantial, yet the money ran like sand through the fingers of John Moodie and Thomas Traill. The tranquillity of the “halcyon days of the bush,” as Susanna had described her first months on Lake Katchewanooka, began to evaporate as the two men exhausted their capital and ran out of cash. Part of the problem was that neither the Moodie nor the Traill property yielded enough wheat or lumber to sell at market. Their crops were so scanty that there was barely enough wheat to last them until Christmas, let alone to leave a bag of flour with the miller in payment for his services. But even better harvests would not have saved the families from the consequences of a major depression throughout North America in the mid1830s, which brought economic stagnation to the backwoods. By the fall of 1835, Susanna had sold most of her own clothes (with the exception of her wedding dress and the handmade baby clothes Mrs. Strickland had sent from England) so that she could pay her servants. Soon the only servants who remained were ones who had nowhere else to go and stayed on without wages. The hired men disappeared; the ambitious plans for outbuildings were shelved; each family began to retrench.

Hunger and want hovered like harpies over the little cabins in the woods. And all four adultsâThomas and Catharine, John and Susannaâbegan to look around for other ways to make money. At first it was a quiet search. It rapidly became desperate.

Susanna had continued to write poetry and sketches. She sent them off to two New Yorkâbased publications, the

Albion

and the

North American Magazine,

and several Torontoâbased periodicals, including the

Canadian Magazine

and the

Canadian Literary Magazine

. They were well received by editors who appreciated the “former Susanna Strickland.” The American poet Sumner Lincoln Fairfield, editor of the

North American Magazine,

described Susanna as having “genius as lofty as her heart is pure.” Susanna's relief at this recognition was almost craven. She replied to Fairfield in January 1835: “Though residing in a small log hut, in the backwoods of Upper Canada, and constantly engaged in the everyday cares of domestic life, I am not so wholly indifferent to praise, as not to feel highly gratified when the spontaneous outpourings of a mind, vividly alive to the beauties of Nature, meets with the approbation of men, of superior worth and genius.” But poetry did not put bread on the Moodie table. Fairfield's payments did not even cover the cost of Susanna's paper and pens.

Catharine was also finding that writing did not pay.

The Backwoods of Canada

was enthusiastically reviewed when it appeared in London early in 1836. The London

Spectator

praised the author's elegance of mind, modesty and “sound practical views,” and declared that “it would be difficult to decide whether [the book] was more entertaining or useful.” The London

Athenaeum

was enchanted by the author, who “is obviously endowed with life's best blessingsâan observant eye, joined to a cheerful and thankful heart.” It recommended the book “for its spirit and truth.” The book was excerpted in several magazines and journals, and noted in

Tait's Edinburgh Magazine

as “written by a lady, who has set a stout heart to a steep hill,⦠and who by spirit, activity, and good humour, has surmounted her difficulties, or converted them into pleasantries.” It had immediately become required reading for any English gentlewoman

considering emigration to British North America, and its sales helped to keep Mr. Charles Knight's shaky publishing house afloat.

Yet the author received only 110 pounds for the copyright to the book, and no royalties on sales. Stuck in the remote depths of a colony, Catharine had little leverage on Charles Knight. The ingenuous optimism that saturates

The Backwoods of Canada

drained away, as the author realized that her bestseller was not going to rescue her from the woods.

By now, the sisters' husbands were dismally discouraged. Both families were afflicted with malaria, which was rampant on the frontier, where settlers were struggling to drain mosquito-infested swamps. After a few days of sweating and shivers, most of the family members recovered fully. But the disease “threw a gloom” on Thomas's spirits, according to Catharine, which he lacked the stamina to shake off. Both men had additional family responsibilities. The Moodies now had four children: Katie, Aggie, Dunbar, and Donald, who was born in May 1836. By 1837, Catharine was the mother of James, four; Katharine Agnes Strickland (Kate), one; and newborn Thomas Henry Strickland (Harry). There were a lot of mouths to feed on a few acres of wheat and potatoes.

Thomas Traill would willingly have sold his farm to the first bidder. Unfortunately, there were no takers. Thomas informed relatives in the Orkneys, in 1836, that “land has been nearly unsaleable for the last two years.” He described his predicament in ghastly detail, adding mournfully that he wished they had emigrated to the West Indies instead of Canada. Then he threw out a pathetic appeal for “anything like a Consulship at some small Foreign Port [where I might live] a life more suitable to my tastes and habits.” The last sentence of his letter is suffused with despair: “But I must live and die, far from many of those that I love most dearly.”

John Dunbar Moodie was in an even worse predicament than his brother-in-law. He had fewer cleared acres and more debts. In yet another of his impetuous business decisions, he had sold his military commission back to his regiment (which would quickly sell it to another bidder), which meant that he no longer had his military half-pay, one

hundred pounds a year, to help him scrape by. With the lump sum he had received in return, he'd bought stock in a Cobourg steamboat company. It was soon obvious that the steamboat stock was worthless, but by then John had used it as surety for various loans. John rarely revealed his anxieties; he knew that this would shake Susanna, who depended on his emotional stability. But he too began to explore other options for their future. First, he tried to interest publishers in the idea of a book about emigration to Upper Canada, similar to his recently published

Ten Years in South Africa.

Next, after seeing an advertisement from the Texas Land Company in the

Albion,

he considered abandoning Upper Canada and moving to Texas. A few months later, he tried a different tack. He wrote to Sir Francis Bond Head, the newly appointed Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, describing his struggles with “embarrassments and difficulties of no ordinary description” and appealing to him for a government appointment that might shield his family from “distress or ruin.” But nothing came of any of these efforts.

Every few weeks, a letter would arrive for Susanna from Agnes Strickland, in England. Although she often enclosed some entirely inappropriate gift, such as silk stockings (“only worn once at court”), Agnes was acutely aware of her sisters' deteriorating fortunes and dwindling hopes. She always tried to send her letters with someone travelling to the colony, since the Moodies' could barely afford to pay for the letters she sent them through the mail. Carefully wrapped in the folded paper (envelopes were still not in use) were two or three silver coins for the children. John and Susanna were too close to starvation to do anything other than spend the precious coins on desperately needed essentials.