Sixteen Brides

Authors: Stephanie Grace Whitson

SIXTEEN

BRIDES

Books by

STEPHANIE GRACE

WHITSON

A Claim of Her Own

Jacob’s List

Unbridled Dreams

Watchers on the Hill

Secrets on the Wind

(3 books in 1)

Walks the Fire

Soaring Eagle

Red Bird

How to Help a Grieving Friend

STEPHANIE GRACE

WHITSON

SIXTEEN

BRIDES

Sixteen Brides

Copyright © 2010

Stephanie Grace Whitson

Cover design by Dan Pitts

Cover illustation by William Graf

Scripture quotations are from the King James Version of the Bible.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

Published by Bethany House Publishers

11400 Hampshire Avenue South

Bloomington, Minnesota 55438

Bethany House Publishers is a division of

Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Whitson, Stephanie Grace.

Sixteen brides / Stephanie Grace Whitson.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-7642-0513-2 (pbk.)

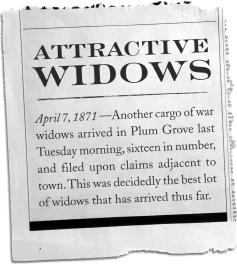

1. War widows—Fiction. 2. Homestead law—Nebraska—Fiction. 3. Women pioneers— Fiction. 4. Frontier and pioneer life—Nebraska—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3573.H555S59 2010

813'.54—dc22

2009041266

DEDICATED TO

the memory of

God’s extraordinary women

in every place

in every time.

And to my Daniel,

the best creative consultant ever . . .

mahalo nui loa . . .

aloha wau ia ’oe.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A

native of southern Illinois, Stephanie Grace Whitson has lived in Nebraska since 1975. She began what she calls “playing with imaginary friends” (writing fiction) when, as a result of teaching her four home-schooled children Nebraska history, she was personally encouraged and challenged by the lives of pioneer women in the West.

Since her first novel,

Walks the Fire,

was published in 1995, Stephanie’s fiction titles have appeared on the ECPA bestseller list numerous times and been finalists for the Christy Award, the Inspirational Readers Choice Award, and ForeWord Magazine’s Book of the Year. Her first nonfiction work,

How to Help a Grieving Friend: a Candid Guide for Those Who Care,

was released in 2005.

In addition to keeping up with her five grown children and two grandchildren, Stephanie enjoys motorcycle trips with her blended family (she was widowed in 2001 and remarried in 2003) and church friends, as well as volunteering at the International Quilt Study Center and Museum in Lincoln, Nebraska. She is currently in graduate school pursuing a Master of Historial Studies degree. Her passionate interests in pioneer women’s history, antique quilts, and French, Italian, and Hawaiian language and culture provide endless storytelling possibilities.

Contact information:

www.stephaniewhitson.com

; [email protected]; Stephanie Grace Whitson, P.O. Box 6905, Lincoln, Nebraska 68506.

CONTENTS

A man’s heart deviseth his way:

but the Lord directeth his steps.

PROVERBS 16:9

A

s the carriage pulled away from Union Station, Caroline Jamison almost panicked and called out to the driver, “Wait! Don’t go! I’ve changed my mind! Take me home!” Her heart racing, Caroline forced herself to turn away.

St. Louis isn’t home. And home doesn’t want you. Daddy told you that in his last letter.

Still, there were times when she entertained a desperate few minutes of hope.

But what if I was standing right there on the veranda. Would he really turn me away? If I told him I was sorry . . . that he was right . . . if I begged . . . what then?

For just a moment the possibility that her father might forget everything and pull her into his arms made Caroline feel almost dizzy with joy. But then she remembered. It had been five years since she’d opened that last envelope, and still she could recite the terse few lines of the last letter posted from General Harlan Sanford of Mulberry Plantation.

Daughter.

We received word today. Langdon now joins his two brothers in glory. Your mother has taken to her bed. The idea that any—or all—of these deeds of war may have been committed by one their sister calls HUSBAND—

The sentence wasn’t finished. Caroline still remembered touching the spot where the ink trailed off toward the edge of the paper, a meandering line that wrenched her heart as she pictured Daddy seated at his desk, suddenly overcome by such a deep emotion he couldn’t control his own hand.

We are bereft of children now. May God have mercy on your soul.

For a moment, as Caroline stood, frozen motionless by uncertainty here on the brick walkway leading up to Union Station, desperate regret and a renewed sense of just how completely alone she was rose up. Panic nearly swept her away. If she didn’t get hold of herself she was going to faint. A few deep breaths would be helpful, but the corset ensuring her eighteen-inch waist wasn’t going to allow for that. She closed her eyes in a vain attempt to hold back the tears.

You don’t dare go home . . . and you don’t dare stay here.

An axle in need of grease squealed as another carriage pulled up to the curb, this one drawn by a perfectly matched team of black geldings. Their coats glistening, their manes plaited with red ribbons, the horses tossed their heads and stamped their great hooves. As the driver called out to calm the team, a coachman hopped down from his perch, but he was too late to open the door for his fare.

One glimpse of the wild-looking man emerging from the polished carriage and Caroline swiped at her tears, snapped open her gold silk parasol, and bent down to pick up her black traveling case.

You’ll make a scene if you faint right now, and the ladies of Mulberry Plantation never make a scene.

The ladies of Mulberry Plantation didn’t associate with the kind of men emerging from that carriage, either. Lifting her chin, Caroline headed toward the station lest one of them offer to escort her up the hill. The last thing she needed today was to have to extricate herself from the unwanted attentions of some dandy dressed up like a poor imitation of Wild Bill Hickok.

Wild Bill Hickok

indeed. Grateful to be thinking about something besides home, she almost smiled at the memory of Thomas, one of the Jamisons’ servants, and the ridiculous hat he’d sported for weeks after seeing Hickok and Buffalo Bill on stage. A hat just like the ones on the heads of the men climbing out of the newly arrived carriage. Only these men didn’t look ridiculous. They looked . . . dangerous. Caroline peered back at them from beneath the edge of her parasol even as she made her way up the hill. The tall one had a certain appeal—if a woman liked that kind of man. Caroline did not.

With every step away from the street and toward the station, her doubt and fear receded. She could do this. After all, it was the only thing that made any sense. No one was coming to rescue her. It was time she rescued herself.

“Painting walls and hanging pictures don’t make a barn into a home, Mama.” Ella Barton looked away from her own face in the mirror just long enough to catch her mother’s eye. “A barn is still a barn.” Shaking her head, she untied the new bonnet. “I’m sorry. I just can’t. You were sweet to buy it, but I look ridiculous.” She put the stylish bonnet back into the open bandbox sitting atop the dresser. “We’ll return it on the way to the station.”

“We will

not

return it.” Mama snatched it up and ran her hand along the upturned brim. She smoothed the nosegay of iridescent feathers just peeking out of the grosgrain ribbon that bordered the crown. “It’s beautiful.”

“Did I say it wasn’t?” Ella turned her back on the mirror. “The problem is not the hat.” Gently she extracted the bonnet from her mother’s grasp and nestled it back into the box. “The old one is better. It suits me.” She settled the lid on the bandbox. “What do I need with a new hat, anyway? I hardly think they parade the latest fashions up and down the street in Cayote, Nebraska.”

“Maybe not,” Mama said. “But you can bet there

will

be a parade when we all arrive. Everyone says women are in short supply out west. That means you can expect a parade of bachelors coming into Cayote as soon as word gets out about the Emigration Society’s arrival.”

Ella crossed the room to where their two traveling cases lay open on the lumpy mattress. “And they will see me as I am—and leave me be. Even if I were interested—which I am not—a new bonnet wouldn’t change anything.” She finished folding her white cotton nightgown into the case as she spoke, especially mindful of the wide border of handmade lace as she closed the lid. It had taken her over thirty hours to make that gown. She wanted it to last.

Mama joined her by the bed, closing and locking her own traveling case as she said, “You don’t

know

what others see when they look at you, Ella. You have lovely eyes.”

Ella snorted in disbelief. “I know what they see. Milton reminded me almost every day.”

“Milton!” Mama spit the name out like spoiled meat. She made two fists and pummeled the air. “I wish I could get my hands on him I’d teach him—”

“Mama.” Ella’s voice was weary. Mama’s opinions about Milton had grown old long ago. “Let him rest in peace. It’s over.”

“Except that it

isn’t

. What he did to you—what he made you feel about yourself—none of that is

over

.”

Ella sighed. It was no use debating Milton Barton with Mama Mothers looked at their daughters and saw the best, which was, in Ella’s case, her eyes. But mothers tended to see

only

the things like beautiful hazel eyes. They ignored broad shoulders and strong frames, large hands and noses.

As Ella lifted her traveling case off the bed and set it on the floor so she could smooth the blanket into place, she glanced toward the mirror. She always had regretted that nose. But simple regret had evolved into something else, thanks to Milton. It was

her

fault he sought other beds. It was

her

fault he wandered. It was

her

fault they had no children.

She wasn’t pretty. She wasn’t feminine. She wasn’t—

S

top

.

Stop the litany. Stop it now. Nothing good comes of it.

What was it Mama always said . . .

forget what lies behind. Press on to hope.

She must do that now, even if she did still hear Milton’s voice at times She was clumsy. She lumbered like a cow. Such a big nose. Such large hands. Such rough skin. She was

barren

. But of all the words Milton flung at her, the ones that hurt most were the ones Ella added to the list herself. She was

gullible

. Gullible and

stupid

to have believed a man could love a woman like her.

And so, after being widowed by the war, having lost her farm and much of herself in the process, Ella moved to town and rented a nondescript room on a nondescript street in St. Louis. She cooked and cleaned at a nice hotel nearby, and kept to herself. She was never asked to stay on, never promoted to serve in the dining room. After all, who would want a cow lumbering about with their fancy china and silver candlesticks? Dark thoughts hung over the widow Barton like a cloud. And then one day she saw Mr. Hamilton Drake’s sign in a milliner’s shop window.

WANTED

, it said in large letters.

ONLY WOMEN NEED APPLY

. Smaller print said that Mr. Hamilton Drake of Dawson County, Nebraska, the organizer of the Ladies Emigration Society, was here in St. Louis to help women

TAKE CONTROL

of their own

DESTINY

by acquiring

LAND IN THEIR OWN NAME

. He invited

ALL INTERESTED LADIES

to meet with him in Parlor A of the Laclede Hotel on any one of three evenings listed. He promised that if women would

HURRY,

they could still acquire

FREE PRIME HOMESTEADS

in the most desirable portions of the county.

Control of her own destiny . . . land in her own name . . . a prime homestead.

Ella stood looking at that sign for a long while. At the first meeting she attended, Mr. Drake produced an “official” copy of the homestead law President Lincoln had signed back in 1862. Ella read it and learned that what Drake said was right. As a single woman and therefore the head of her own “household,” Ella could file on a homestead. And Ella knew land. She knew livestock and crops and plows. She knew when to plant and how to harvest. She also knew there was little, if any, chance a man would ever love her, and even if some fool tried, how would she ever know if it was sincere? But Ella knew something else, too. For the first time in a very long while, Ella knew hope.

Ella looked into the mirror and smiled. Mama was right. The simply dressed woman with the plain face did have rather nice eyes. She glanced at Mama in the mirror. Dear Mama, with her tiny waist and petite stature. Mama, with her lively sense of humor and youthful spirit What, Ella thought, would she have ever done without Mama?

“Ella.” Mama patted her shoulder. “Stop riding the clouds and come back to earth.” When Ella blinked and looked at her, Mama put her hand atop the bandbox. “I asked if you’re sure about the new hat.”

“I’m sure.” Ella reached for the old brown one hanging on a hook by the door.

With a dramatic sigh, Mama took the bandbox in hand and opened the door.

Ella picked up their two suitcases and followed her out into the hall and downstairs. As they headed toward the train station by way of the milliner’s, neither woman looked back.

The resolve that had propelled Caroline Jamison up the hill and into Union Station faded the instant she lowered her parasol just inside the door. She hesitated, gazing at the scores of people buying tickets, hurrying toward the tracks, seated in the lunch room sipping tea, browsing at the newsstand. Her head hurt. Her kid leather gloves were growing damp. Perspiration trickled down her back. She was feeling shaky again.

The members of the Ladies Emigration Society were supposed to proceed through the station and gather on the siding near Track Number 2. Mr. Drake had said he expected almost a train-car full of women to join the Society. Caroline wasn’t ready to meet all those strangers. She looked toward the tracks.

Oh no. Please no. Not the sisters.

Caroline had especially hoped those four would have talked each other out of heading west. At the thought of facing those four—and maybe a few dozen women just like them—Caroline found an empty bench and sat down.

Pulling her traveling case onto her lap, she clung to the handle with one hand and her parasol with the other even as she tried to calm herself.

Close your eyes. Think of something else. Think about . . . the rose garden. Remember how wonderful those yellow ones on the arbor smelled when they bloomed? Can you hear old James humming to himself while he trimmed the hedge?

Shutting out the sounds of the bustling train station and thinking about the garden helped. She stopped trembling.

There, now. That’s better.